Bequeathing Rules under Succession Laws in India Based on Domicile and Religion: A Legal Analysis

Introduction

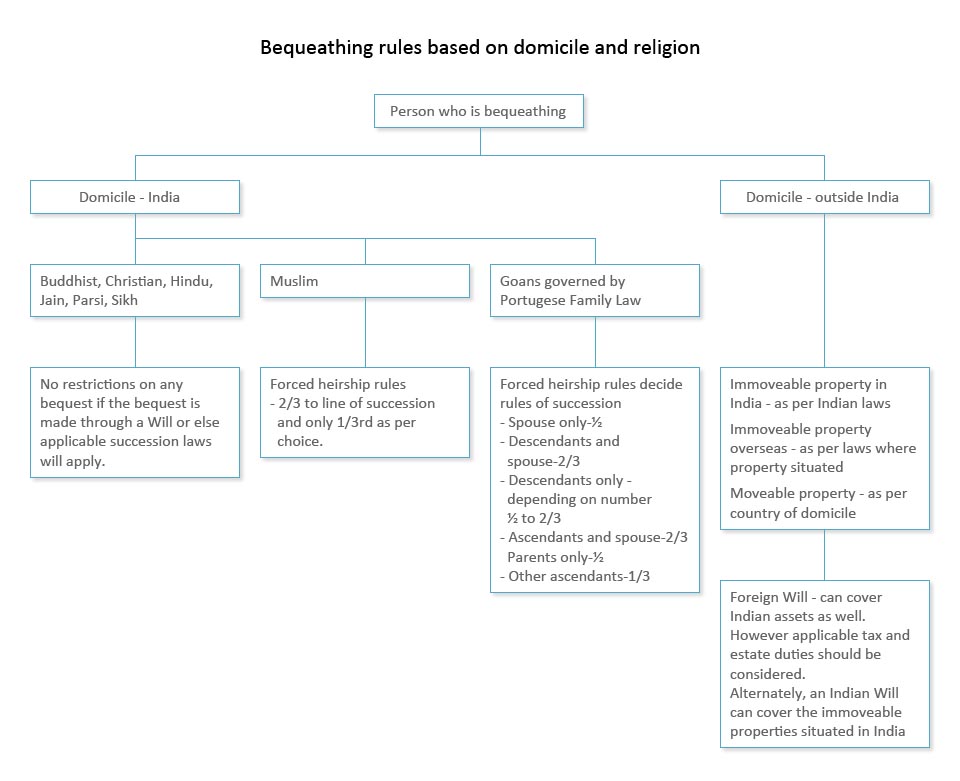

India’s succession and inheritance framework represents a unique amalgamation of religious personal laws, statutory provisions, and constitutional principles. The determination of how property devolves upon death is not governed by a uniform code but rather depends critically on two fundamental factors: the religion of the deceased and their domicile at the time of death. This intricate legal architecture creates a multi-layered system where testamentary freedom varies dramatically across communities, and the applicability of laws shifts based on geographical and jurisdictional considerations.

The intersection of domicile and religion in governing succession laws in India reflects the country’s pluralistic character while simultaneously raising questions about equality and uniformity in inheritance rights. Understanding these principles requires examining how different personal laws operate, the role of domicile in determining applicable legislation, and the constitutional framework that permits such diversity.

The Concept of Domicile in Succession Law

Domicile functions as a connecting factor that determines which legal system governs an individual’s succession rights, particularly concerning movable property. The Indian Succession Act, 1925 establishes fundamental principles regarding the role of domicile in succession matters through its opening provisions.

Section 5 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 establishes two distinct rules for succession based on property classification [1]. Subsection (1) provides that “Succession to the immovable property in India of a person deceased shall be regulated by the law of India, wherever such person may have had his domicile at the time of his death.” This means immovable property situated in India will always be governed by Indian law regardless of where the deceased was domiciled. Subsection (2) states that “Succession to the movable property of a person deceased is regulated by the law of the country in which such person had his domicile at the time of his death” [1].

This bifurcation creates practical implications for individuals with cross-border connections. For instance, if an Indian Christian domiciled in France dies leaving movable property in England and immovable property in India, the succession to movable property would be governed by French law while immovable property in India would be governed by Indian law. The Act further clarifies in Section 6 that a person can have only one domicile for succession purposes regarding movable property, preventing jurisdictional conflicts [1].

Domicile differs fundamentally from mere residence. While residence indicates physical presence in a location, domicile requires both residence and the intention to remain indefinitely in that place. Section 10 of the Indian Succession Act defines how a person acquires a new domicile by taking up fixed habitation in a country other than their domicile of origin [1]. For Christians in India, domicile historically played an even more granular role, as different states within India applied varying succession laws based on regional domicile, though these have largely been harmonized under the Indian Succession Act.

Hindu Succession: The Interplay of Personal Law and Statutory Reform

The Hindu Succession Act, 1956 governs inheritance among Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs, representing a significant codification and reform of traditional Hindu law [2]. Unlike the Christian framework where domicile plays a critical role in determining applicable law, Hindu succession operates primarily on religious identity rather than domicile considerations within India.

Section 2 of the Hindu Succession Act defines its applicability broadly, extending to any person who is Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, or Sikh by religion, as well as to any person who is not a Muslim, Christian, Parsi, or Jew unless proven otherwise [2]. This expansive definition creates a presumptive application to most Indians unless they fall under other specified religious categories.

A significant aspect of Hindu law relates to how domicile historically affected certain communities. Section 2(2) addresses special cases, noting that the Act does not apply to members of Scheduled Tribes unless specifically directed by the Central Government. Additionally, Section 2(1)(b) references communities largely domiciled in erstwhile Travancore-Cochin or Madras states who were governed by systems tracing descent through the female line, such as the Marumakkattayam and Aliyasantana systems [2].

The Hindu Succession Act established gender-neutral inheritance principles, though it took the 2005 Amendment to fully achieve equality. Section 6 of the Act, as amended in 2005, confers coparcenary rights on daughters equal to sons in joint Hindu family property governed by Mitakshara law [3]. The amendment marked a watershed moment in Indian succession jurisprudence, dismantling centuries of patriarchal inheritance structures.

A critical issue that emerged concerned children born from void or voidable marriages. Section 16 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 addresses the legitimacy and inheritance rights of such children. In the landmark case of Revanasiddappa v. Mallikarjun decided by a Constitution Bench in September 2023, the Supreme Court clarified that children born from invalid marriages are entitled to their parents’ share in ancestral property, though they do not become coparceners themselves [4]. The Court held that while Section 16(3) of the Hindu Marriage Act grants legitimacy to such children, their rights extend only to what their parents would have received upon a notional partition, not to the entire coparcenary property.

Muslim Law: Shariat Principles and Testamentary Restrictions

Muslim personal law governing succession operates under principles derived from Shariat, codified through the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 [5]. This legislation represents British colonial policy to systematize Islamic law application among Indian Muslims, and it continues to govern succession matters for Muslims who have not married under the Special Marriage Act, 1954.

Section 2 of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 provides that “Notwithstanding any custom or usage to the contrary, in all questions (save questions relating to agricultural land) regarding intestate succession, special property of females, including personal property inherited or obtained under contract or gift or any other provision of Personal Law, marriage, dissolution of marriage, including talaq, ila, zihar, lian, khula and mubaraat, maintenance, dower, guardianship, gifts, trusts and trust properties, and wakfs (other than charities and charitable institutions and charitable and religious endowments) the rule of decision in cases where the parties are Muslims shall be the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat)” [5].

The most distinctive feature of Muslim succession law concerns testamentary restrictions. Unlike Hindu or Christian law where individuals possess complete freedom to bequeath their entire estate through a will, Muslim law imposes a strict one-third limitation. A Muslim testator cannot bequeath more than one-third of their net estate to non-heirs without obtaining consent from legal heirs after death [6]. This restriction reflects Quranic principles balancing testamentary freedom with protection of family inheritance rights.

Furthermore, under classical Sunni jurisprudence, a bequest to a legal heir requires consent from all other heirs, though this rule has been subject to debate and reform proposals. The case of Illyas v. Badshah decided by the Madhya Pradesh High Court in 1990 examined customary variations, holding that customs limiting testamentary choice are valid if not contrary to public policy or fundamental Mohammedan law principles [6].

Importantly, if a Muslim marries under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, their succession is governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925 rather than Muslim personal law, granting them complete testamentary freedom [6]. This creates a significant distinction based on the form of marriage rather than religion alone.

Christian Succession: The Indian Succession Act Framework

Christian succession in India operates under the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which also governs Parsis, Jews, and those not covered by other personal laws [7]. The Act provides relatively uniform rules without the patriarchal biases found in traditional Hindu law or the testamentary restrictions of Muslim law.

Section 2(d) of the Indian Succession Act defines an “Indian Christian” as a native of India who is or in good faith claims to be of unmixed Asiatic descent and who professes any form of Christian religion [7]. This definition is significant as it determines the applicability of intestate succession provisions specifically designed for Indian Christians under Chapter II of the Act.

Section 30 of the Act defines intestate succession, stating that a person is deemed to die intestate concerning all property they have not effectively disposed of through testamentary disposition [7]. For Indian Christians dying intestate, property devolves according to rules in Chapter II, which recognize three types of heirs: the spouse, lineal descendants, and kindred.

Christians possess complete testamentary freedom under the Indian Succession Act. Unlike Muslims, they can bequeath their entire estate to any person or entity without restriction. The only formal requirements are that the testator must be of sound mind, not a minor, and the will must be in writing and signed by the testator or someone on their behalf in their presence [8].

The issue of illegitimate children under Christian law presented significant challenges. Historically, Christian law recognized only legitimate kinship, excluding illegitimate children from inheritance. However, in the groundbreaking decision of Jane Anthony v. V.M. Siyath rendered by the Kerala High Court in 2008, the Court advocated for legislative reform to grant inheritance rights to illegitimate children born to Christian parents [9]. The Court held that children born to parents living as husband and wife should be considered legitimate for succession purposes, calling upon Parliament to enact legislation conferring inheritance rights on all illegitimate children irrespective of religion, analogous to maintenance rights under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Domicile Variations Among Indian Christians

The role of domicile in Christian succession warrants special attention as it created unique complications within the Indian Christian community. Until January 1986, Christians in Kerala were governed by different Acts based on domicile: those domiciled in Cochin followed the Cochin Christian Succession Act, 1921, while Travancore Christians were governed by the Travancore Christian Succession Act, 1916 [8]. These Acts have since been repealed, bringing all under the Indian Succession Act, 1925, though some Protestant and Tamil Christian communities in certain regions continue following customary laws.

Section 15 of the Indian Succession Act provides that upon marriage, a wife automatically acquires her husband’s domicile and retains it during the subsistence of marriage [8]. This provision, while criticized for perpetuating gender inequality, remains part of the statutory framework and affects determination of applicable law for movable property succession.

Constitutional Considerations and Uniform Civil Code Debate

The coexistence of multiple personal laws based on religion exists within a constitutional framework that guarantees both religious freedom and equality. Article 25 of the Constitution protects freedom of religion, while Article 44 envisions a Uniform Civil Code as a Directive Principle of State Policy. This tension between religious autonomy and legal uniformity remains unresolved.

Article 14 guarantees equality before law, raising questions about whether differential treatment based on religion violates constitutional equality norms. Courts have generally held that personal laws constitute reasonable classification with intelligible differentia, particularly given India’s cultural diversity and constitutional protection of religious practices.

Recent challenges to Muslim personal law provisions, including petitions questioning the one-third testamentary limitation, argue that compulsory application of religious inheritance rules violates Article 14 by creating arbitrary classifications between Muslims married under different laws and infringing upon personal liberty [6]. These petitions remain pending before the Supreme Court and could potentially reshape Muslim testamentary law.

Comparative Analysis of Testamentary Freedom

The three major personal law systems demonstrate stark differences in testamentary freedom. Hindus, following the Hindu Succession Act, possess complete freedom to dispose of their property through wills without restriction [2]. Christians governed by the Indian Succession Act similarly enjoy unrestricted testamentary capacity [8]. Muslims, however, face the one-third limitation, creating inequality in the ability to direct property disposition [5][6].

These differences become particularly pronounced in scenarios involving interfaith families or individuals with property interests across jurisdictions. The choice of marriage law—whether under personal religious law or the Special Marriage Act—can fundamentally alter succession rights, creating strategic considerations for estate planning.

Conclusion

Bequeathing rules under the succession laws in India remain inextricably linked to both domicile and religion, creating a complex tapestry of applicable legal regimes. The Indian Succession Act’s domicile-based provisions for Christians and others, the religion-centric Hindu Succession Act, and the Shariat-governed Muslim succession framework reflect India’s commitment to religious pluralism while simultaneously raising ongoing questions about uniformity and equality.

The evolution of these laws through judicial interpretation, particularly regarding illegitimate children’s rights and gender equality, demonstrates gradual reform within traditional frameworks. However, fundamental differences in testamentary freedom and succession rights across communities continue to generate debate about the desirability and feasibility of a Uniform Civil Code.

Understanding the interplay of domicile and religion in succession matters is essential for estate planning, legal practice, and policy formulation in contemporary India. As the nation continues balancing religious diversity with constitutional equality, succession law remains a critical arena where these tensions manifest most acutely.

References

[1] The Indian Succession Act, 1925. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1450343/

[2] The Hindu Succession Act, 1956. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1713

[3] Section 6, The Hindu Succession Act, 1956. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1883337/

[4] Revanasiddappa v. Mallikarjun, 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1087. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/30241407/

[5] The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1325952/

[6] Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937 – Analysis. https://blog.ipleaders.in/the-muslim-personal-law-shariat-act-1937/

[7] Christian Law of Inheritance. https://lawbhoomi.com/christian-law-of-inheritance/

[8] Succession Under Christian Laws. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/succession-under-christian-laws-apurva-agarwal

[9] Jane Anthony v. V.M. Siyath, 2008 (4) KLT 1002. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/419909/

Whatsapp

Whatsapp