The Ambit of Marriage and Gift under Hindu Law

Introduction

Hindu law represents one of the world’s most ancient and enduring legal systems, with its foundations deeply rooted in sacred texts and traditions spanning over millennia. The concepts of marriage and gift under Hindu law embody fundamental principles that govern personal relationships and property transfers within Hindu society. The codification of Hindu personal laws, particularly through the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 [1] and the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 [2], has brought systematic legal framework to these traditional institutions while preserving their essential spiritual and cultural character.

The legal framework governing Hindu marriages and gifts reflects a careful balance between ancient traditions and modern legislative requirements. This intricate system addresses the sacred nature of Hindu matrimonial relationships while establishing clear legal parameters for property transfers through gift mechanisms. Understanding these provisions requires examination of both statutory law and judicial interpretations that have shaped contemporary Hindu personal law.

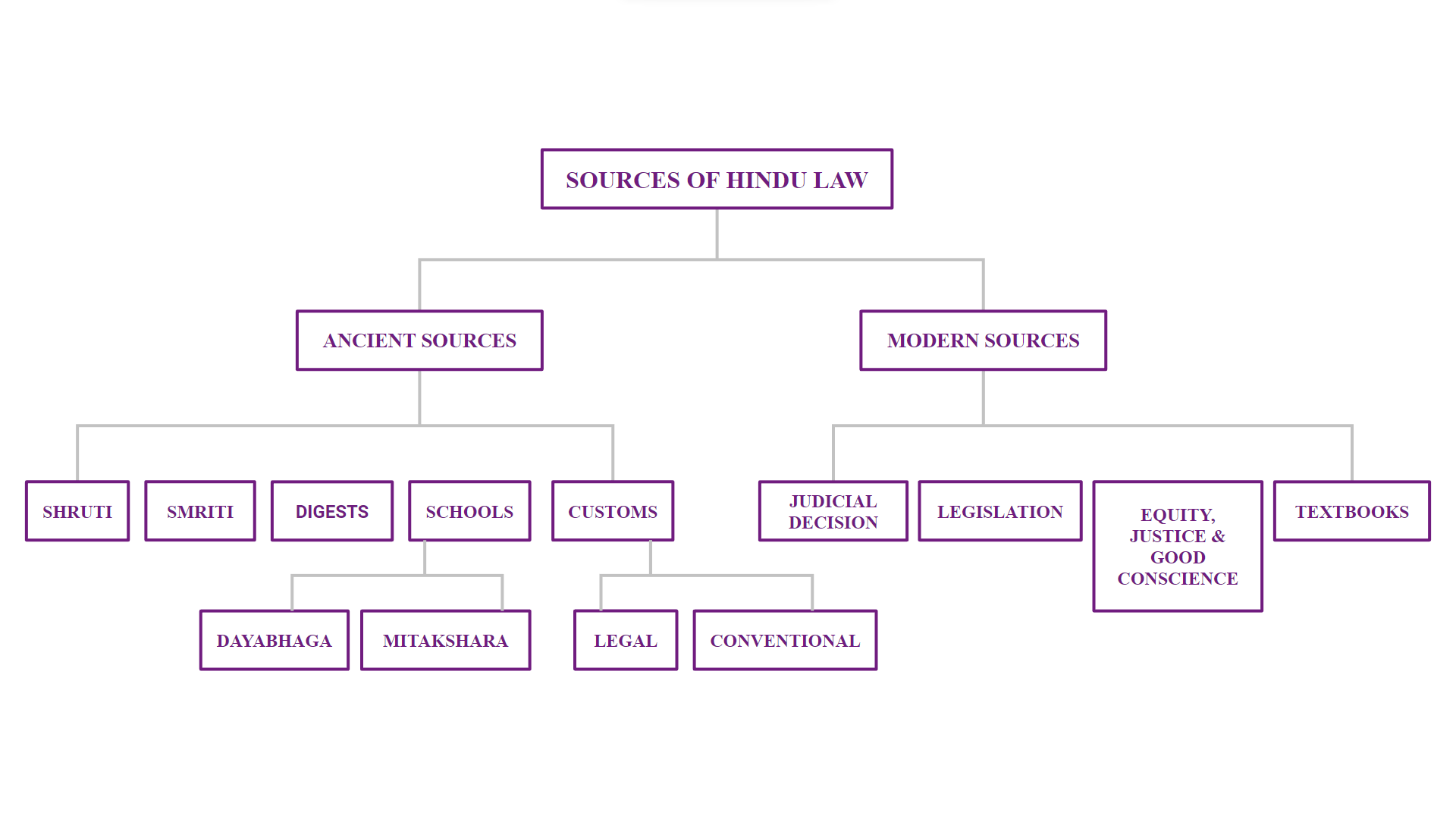

Historical Foundation and Evolution of Hindu Law

Hindu law derives its authority from ancient texts including the Vedas, Smritis, and various commentaries by learned jurists. The system evolved through centuries of scholarly interpretation and judicial application, ultimately culminating in legislative codification during the post-independence period. The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, emerged as part of the broader Hindu Code Bills initiative, alongside the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956, and the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 [3].

The legislative framework sought to address inconsistencies in customary practices while maintaining the essential character of Hindu personal law. This codification process represented a significant milestone in harmonizing diverse regional customs and traditions under a unified legal structure applicable to all Hindus, including Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains, as specifically provided under Section 2 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 [4].

Definition and Scope of Hindu Marriage

Legal Framework and Applicability

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 provides a comprehensive definition of who qualifies as a Hindu for the purposes of marriage law. Section 2 of the Act establishes its applicability to any person who is a Hindu by religion in any of its forms or developments, including Virashaivas, Lingayats, or followers of the Brahmo Samaj, Prarthana Samaj, or Arya Samaj [5]. The Act further extends to persons who are Buddhist, Jain, or Sikh by religion, thereby encompassing the broader Hindu cultural and religious spectrum.

The legislative framework recognizes both converts and reconverts to Hinduism, ensuring their equal protection under Hindu personal law. This inclusive approach acknowledges the dynamic nature of religious identity in contemporary Indian society while maintaining the integrity of traditional Hindu marriage practices.

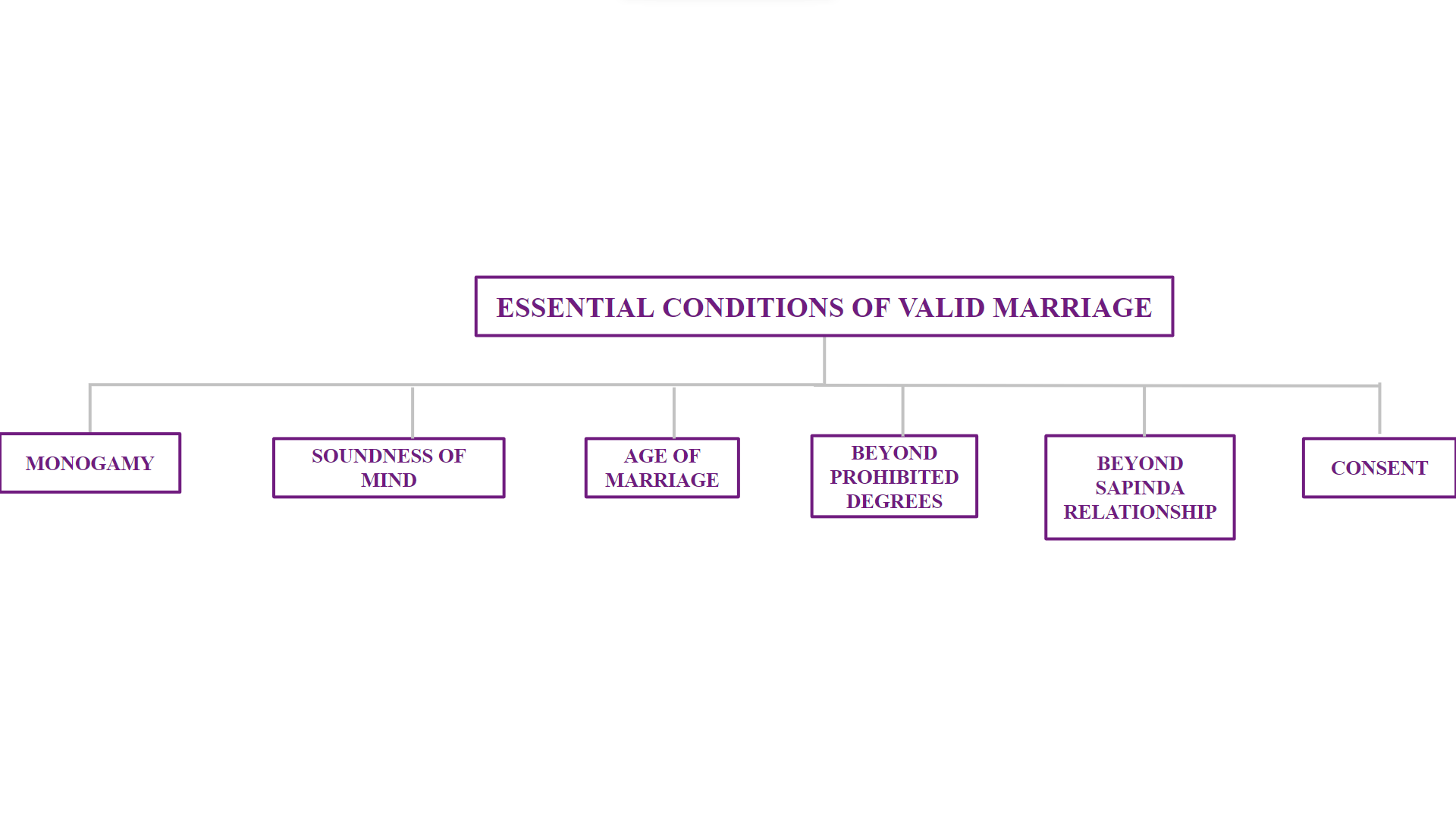

Essential Conditions for Valid Hindu Marriage

Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 establishes five fundamental conditions that must be fulfilled for a valid Hindu marriage [6]:

Monogamy Requirement: Neither party should have a living spouse at the time of marriage. This provision, enshrined in Section 5(i), mandates strict monogamy and prohibits polygamous relationships. The Supreme Court in Lily Thomas v. Union of India [7] reaffirmed this principle, emphasizing that bigamy under Hindu law is void and punishable, regardless of religious conversion attempts to circumvent this requirement.

Mental Capacity and Soundness: Both parties must be capable of giving valid consent and should not suffer from mental disorder that renders them unfit for marriage and procreation of children. This condition ensures that both spouses can understand the nature and consequences of the matrimonial relationship.

Age Requirements: The bridegroom must have completed twenty-one years and the bride eighteen years at the time of marriage. These age requirements were established to ensure physical and mental maturity adequate for marriage responsibilities.

Prohibited Degrees of Relationship: The parties must not be within degrees of prohibited relationship unless custom permits such marriage. This provision prevents marriages between closely related individuals, maintaining genetic and social considerations inherent in traditional Hindu law.

Sapinda Relationship Restrictions: The parties should not be sapindas of each other unless customary usage permits such union. The sapinda relationship extends to the third generation on the mother’s side and fifth generation on the father’s side, as defined in Section 3(f) of the Act [8].

Marriage Ceremonies and Rituals

Section 7 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 recognizes the ceremonial aspect of Hindu marriage, stating that a Hindu marriage may be solemnized according to the customary rites and ceremonies of either party [9]. The provision specifically acknowledges the saptapadi ceremony, declaring that when such rites include the taking of seven steps by the bridegroom and bride jointly before the sacred fire, the marriage becomes complete and binding upon the seventh step.

The Supreme Court in recent decisions has emphasized that mere registration without proper ceremony does not constitute a valid Hindu marriage [10]. The Court stressed that marriage ceremonies are sacred under the Hindu Marriage Act as they provide a lifelong, dignity-affirming, equal, consensual, and healthy union of two individuals.

The Concept of Gift under Hindu Law

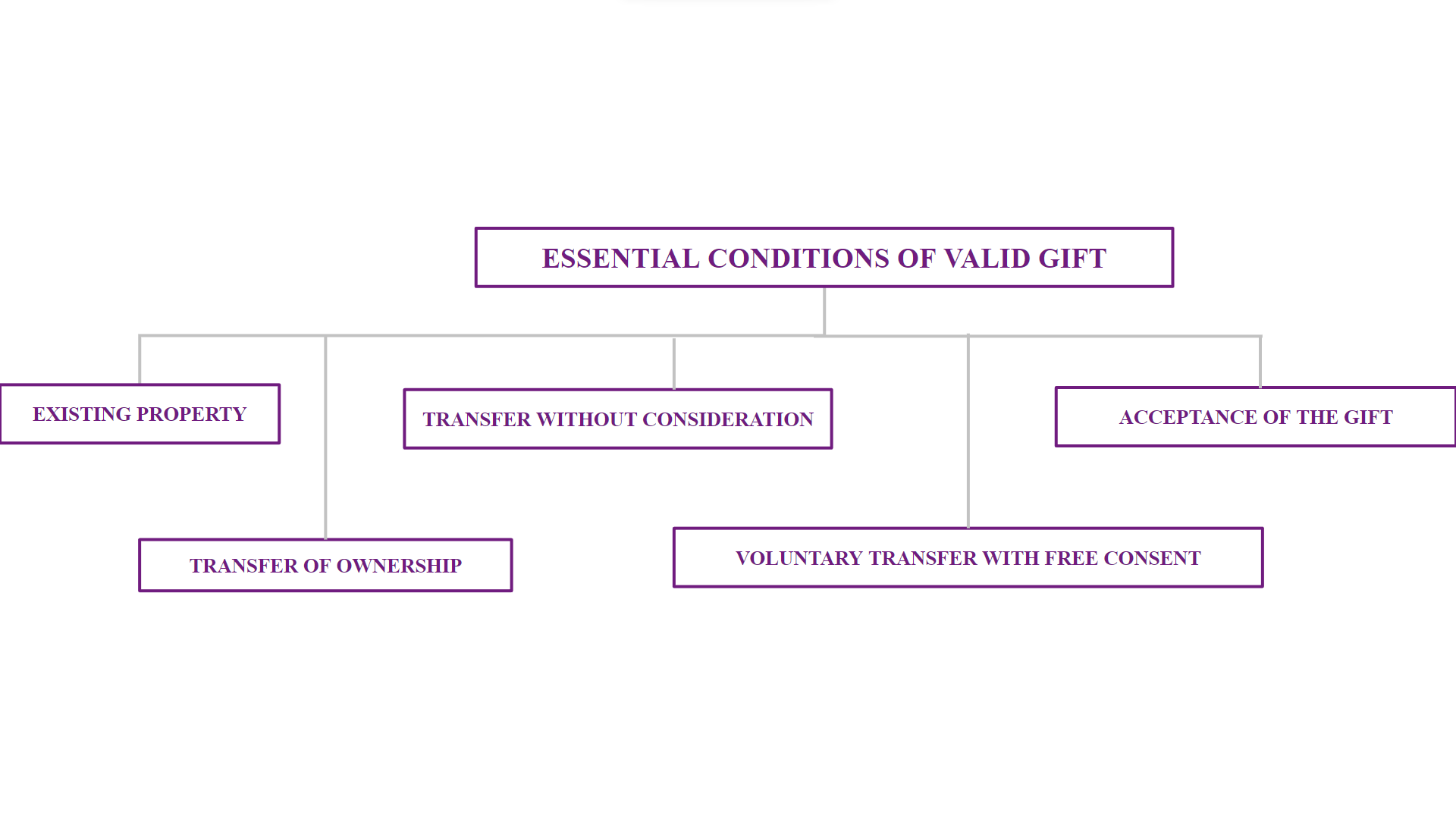

Statutory Framework under Transfer of Property Act, 1882

The Transfer of Property Act, 1882 provides the primary legal framework governing gifts in India, including those made by Hindus. Section 122 defines a gift as “the transfer of certain existing moveable or immovable property made voluntarily and without consideration, by one person, called the donor, to another, called the donee, and accepted by or on behalf of the donee” [11].

This definition establishes several essential elements that distinguish gifts from other forms of property transfer. The requirement of existing property ensures that only tangible assets can form the subject matter of a gift, while the voluntary nature and absence of consideration characterize the gratuitous nature of such transfers.

Essential Elements of a Valid Gift

Existing Property Requirement: The property subject to gift must be in existence at the time of making the gift and must be transferable under Section 5 of the Transfer of Property Act. Gifts of future property are deemed void under Section 124, as they constitute mere promises unenforceable by law [12].

Transfer of Ownership: The donor must divest absolute interest in the property and vest it in the donee. This transfer encompasses all rights and liabilities associated with the property, requiring the donor to have clear ownership rights over the gifted asset.

Voluntary Transfer without Consideration: The gift must be gratuitous, meaning ownership transfers without any consideration in monetary terms. The Supreme Court has consistently held that mutual love and affection do not constitute pecuniary consideration, thereby qualifying such transfers as valid gifts [13].

Acceptance by Donee: The donee must accept the gift, either expressly or through conduct. Section 122 specifies that acceptance must occur during the donor’s lifetime while they remain capable of giving. Acceptance may be inferred from taking possession of property or title deeds [14].

Formalities for Gift Execution

Section 123 of the Transfer of Property Act prescribes different formalities based on the nature of property being gifted. For immovable property, registration is mandatory regardless of value, while movable property may be transferred through delivery of possession or registered instrument [15].

The requirement of registration for immovable property ensures legal certainty and provides documentary evidence of the transfer. However, the Supreme Court has clarified that registration alone cannot validate an otherwise invalid gift that fails to meet substantive requirements.

Special Provisions and Judicial Interpretations

Onerous Gifts and Universal Donee Concept

Section 127 addresses onerous gifts where liabilities exceed benefits. The provision embodies the principle of “qui sentit commodum sentire debet et onus,” meaning one who accepts benefits must also bear burdens [16]. When a gift comprises both beneficial and burdensome property, the donee must accept or reject the entire gift.

Section 128 recognizes the concept of universal donee, making such persons liable for all debts and liabilities of the donor to the extent of gifted property. This provision protects creditor interests while limiting donee liability to the value of received assets.

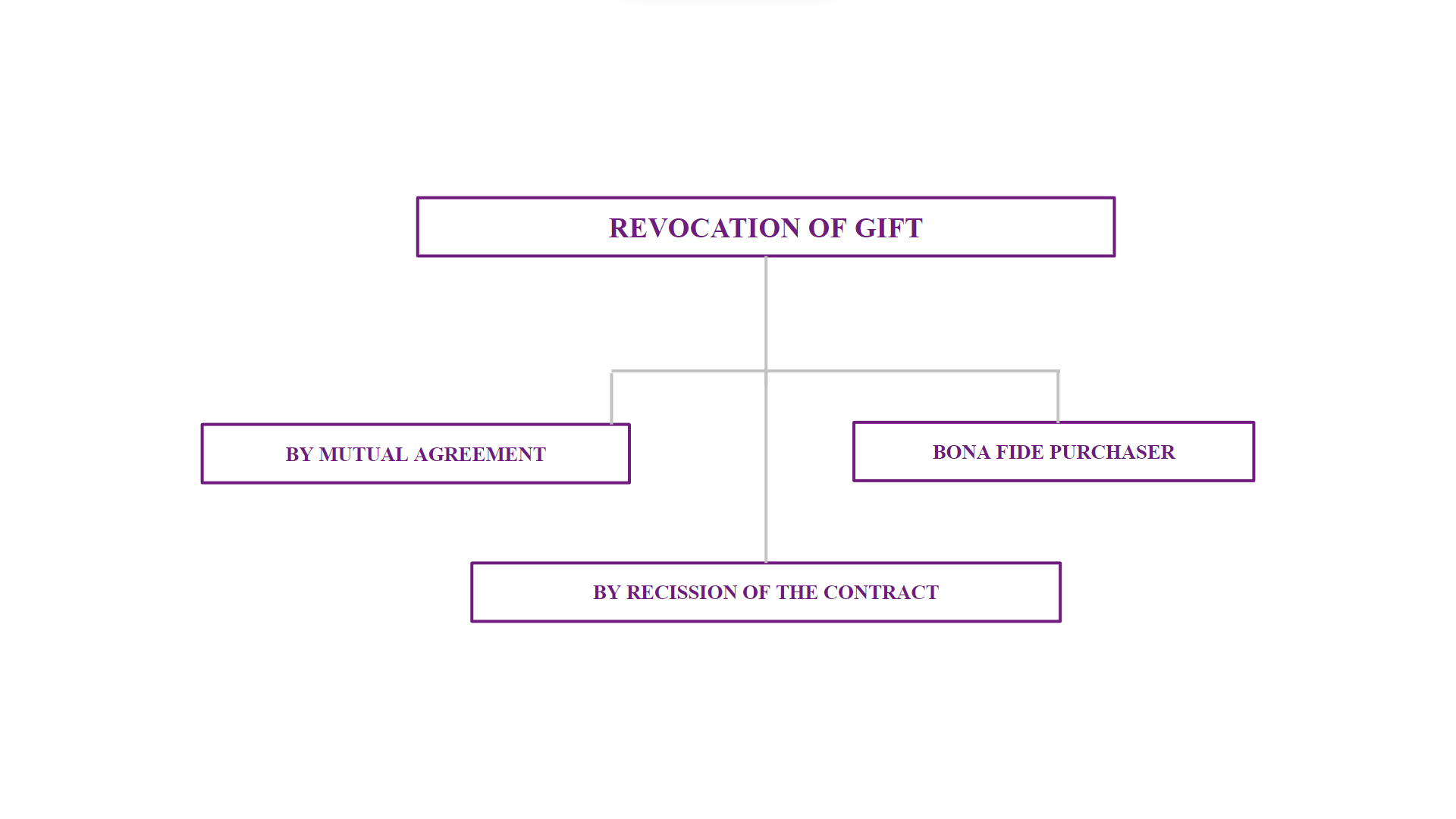

Revocation of Gifts

Section 126 provides two grounds for gift revocation: mutual agreement and rescission of contract. Gifts may be revoked upon occurrence of events not dependent solely on donor’s will, provided such conditions are expressly laid down and mutually agreed upon [17].

The provision also permits revocation on grounds applicable to contract rescission under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, including coercion, undue influence, fraud, and misrepresentation. Such revocation rights are personal to the donor and cannot be transferred, though legal heirs may pursue revocation after the donor’s death.

Marriage as Gift: The Concept of Kanyadan

Hindu tradition conceptualizes marriage as kanyadan, literally meaning “gift of a daughter.” This ancient practice represents the ceremonial transfer of a daughter from her natal family to her husband’s family, symbolizing the father’s relinquishment of guardianship and the husband’s acceptance of responsibility for the bride’s welfare [18].

The Vedic conception of marriage as described in Rigveda hymn 10.85 emphasizes the sacramental nature of this union, where the bride is considered the most precious gift that can be bestowed. This understanding transcends mere property transfer, embodying spiritual and social transformation of relationships between families.

Contemporary legal interpretation recognizes kanyadan as a ceremonial aspect of Hindu marriage while ensuring that such traditions align with constitutional principles of gender equality and individual dignity. The practice has evolved to emphasize mutual consent and partnership rather than unilateral transfer of authority.

Landmark Judicial Decisions

Marriage Validity and Ceremonial Requirements

In the landmark case concerning marriage validity, the Supreme Court established that Hindu marriage requires both compliance with statutory conditions and performance of prescribed ceremonies [19]. The Court emphasized that marriage represents a sacred union witnessed by fire itself, requiring proper ceremonial solemnization beyond mere legal documentation.

The judicial approach recognizes the dual nature of Hindu marriage as both legal contract and religious sacrament. This understanding ensures that marriages maintain their spiritual significance while conforming to legal requirements for recognition and enforcement.

Gift-Related Jurisprudence

Courts have consistently upheld the principle that gifts must satisfy all statutory requirements for validity. In cases involving disputed gifts, the Supreme Court has emphasized the importance of clear evidence regarding donor’s intention, voluntary nature of transfer, and proper acceptance by donee [20].

The judiciary has also clarified that customary gifts within Hindu families, including those made during marriage ceremonies, remain subject to Transfer of Property Act provisions unless specifically exempted by personal law or custom.

Contemporary Applications and Regulatory Framework

Registration and Documentation

The Hindu Marriage Act provides for optional registration of marriages under Section 8, enabling state governments to establish registration procedures [21]. While registration facilitates proof of marriage, it cannot substitute for proper ceremonial solemnization required under Section 7.

Similarly, gift transactions require careful documentation to ensure legal validity and prevent future disputes. Proper registration of gift deeds for immovable property provides legal certainty and protects against fraudulent claims.

Enforcement Mechanisms

Courts possess jurisdiction to determine marriage validity and resolve gift-related disputes under respective statutory provisions. The legal framework provides adequate remedies for addressing violations while maintaining respect for traditional practices and customs.

Enforcement procedures ensure that parties cannot escape legal consequences through technical manipulations or procedural violations. The comprehensive regulatory structure protects legitimate interests while preventing abuse of legal provisions.

Modern Challenges and Legal Adaptations

Gender Equality and Constitutional Compliance

Contemporary interpretation of Hindu marriage and gift laws emphasizes constitutional principles of gender equality and individual autonomy. Courts have evolved traditional concepts to ensure compliance with fundamental rights while preserving essential cultural and religious characteristics.

The legal framework continues adapting to address modern challenges including women’s property rights, domestic violence, and changing family structures. This evolution maintains the delicate balance between tradition and progressive legal development.

Digital Age Implications

Modern technology presents new challenges for traditional concepts of marriage and gift documentation. Electronic records, digital signatures, and online registration systems require careful integration with established legal frameworks to ensure continued effectiveness.

The legal system must adapt to accommodate technological advances while maintaining the integrity and authenticity of traditional ceremonies and documentation processes.

Conclusion

The ambit of marriage and gift under Hindu law represents a sophisticated legal framework that balances ancient wisdom with contemporary requirements. The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 and Transfer of Property Act, 1882 provide comprehensive regulatory structures that preserve traditional values while ensuring legal certainty and protection for all parties.

The evolution of these legal concepts demonstrates the dynamic nature of Hindu personal law and its capacity for adaptation without losing essential character. As society continues evolving, the legal framework must maintain this delicate equilibrium between tradition and progress, ensuring that Hindu marriage and gift institutions remain relevant and effective in addressing contemporary needs while honoring their sacred heritage.

The judicial interpretation of these provisions reflects a nuanced understanding of cultural values and legal requirements, providing a robust foundation for resolving disputes and ensuring justice. This comprehensive legal framework continues serving as a model for integrating religious traditions with modern legal systems, demonstrating the enduring relevance of Hindu law in contemporary Indian society.

References

[1] Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, Act No. 25 of 1955,

[2] Transfer of Property Act, 1882, Act No. 4 of 1882, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2338

[3] Blog.ipleaders.in, “An overview of Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA),” https://blog.ipleaders.in/hindu-marriage-act-1955/

[4] Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, Section 2, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/590166/

[5] Wikipedia, “Hindu Marriage Act, 1955,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Marriage_Act,_1955

[6] Netlawman.co.in, “Hindu Marriage Act 1955 | Summary of key points,” https://www.netlawman.co.in/ia/hindu-marriage-act-1955

[7] Defactojudiciary.in, “HINDU LAWS (Landmark Judgement),” https://www.defactojudiciary.in/notes/hindu-laws-landmark-judgement

[8] Drishtijudiciary.com, “Marriage under Hindu Law,” https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/to-the-point/ttp-hindu-law/marriage-under-hindu-law

[9] Cheggindia.com, “Revolutionary Hindu Marriage Act 1955,” https://www.cheggindia.com/general-knowledge/hindu-marriage-act/

[10] Deccan Herald, “Supreme Court says mere registration in absence of ceremony not a valid marriage,” https://www.deccanherald.com/india/supreme-court-says-mere-registration-in-absence-of-ceremony-not-a-valid-marriage-under-hindu-marriage-act-3002652

[11] Indiankanoon.org, “Section 122 in The Transfer Of Property Act, 1882,” https://indiankanoon.org/doc/881325/

[12] Blog.ipleaders.in, “Concept of gift under the Transfer of Property Act, 1882,” https://blog.ipleaders.in/concept-of-gift-under-the-transfer-of-property-act-1882/

[13] Drishtijudiciary.com, “Gifts under Transfer of Property Act, 1882,” https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/ttp-transfer-of-property-act/Gifts%20under%20Transfer%20of%20Property%20Act,%201882

[14] LinkedIn, “A study of the provisions of Gift under the Transfer of Property Act, 1882,” https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/study-provisions-gift-under-transfer-property-act-1882-rupali-ranait-kmknf

[15] KanoonGPT.in, “Section 122: Gift defined | The Transfer of Property Act, 1882,” https://kanoongpt.in/bare-acts/the-transfer-of-property-act-1882/section-122

Whatsapp

Whatsapp