Constitutional Validity and Critical Analysis of the Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 2020: A Legal Framework for Property Protection

Introduction

The Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 2020 represents a significant legislative intervention in property law, enacted to address the growing menace of illegal land occupation and protect legitimate property rights in Gujarat. Coming into force on August 29, 2020, this legislation marked Gujarat’s entry as the fourth state in India to enact specific anti-land grabbing legislation, following Andhra Pradesh (1982), Assam (2010), and Karnataka (2016). The Act’s constitutional validity was recently upheld by the Gujarat High Court in the landmark case of Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave & Anr. v. State of Gujarat & Ors [1], despite significant constitutional challenges and criticism regarding its stringent provisions.

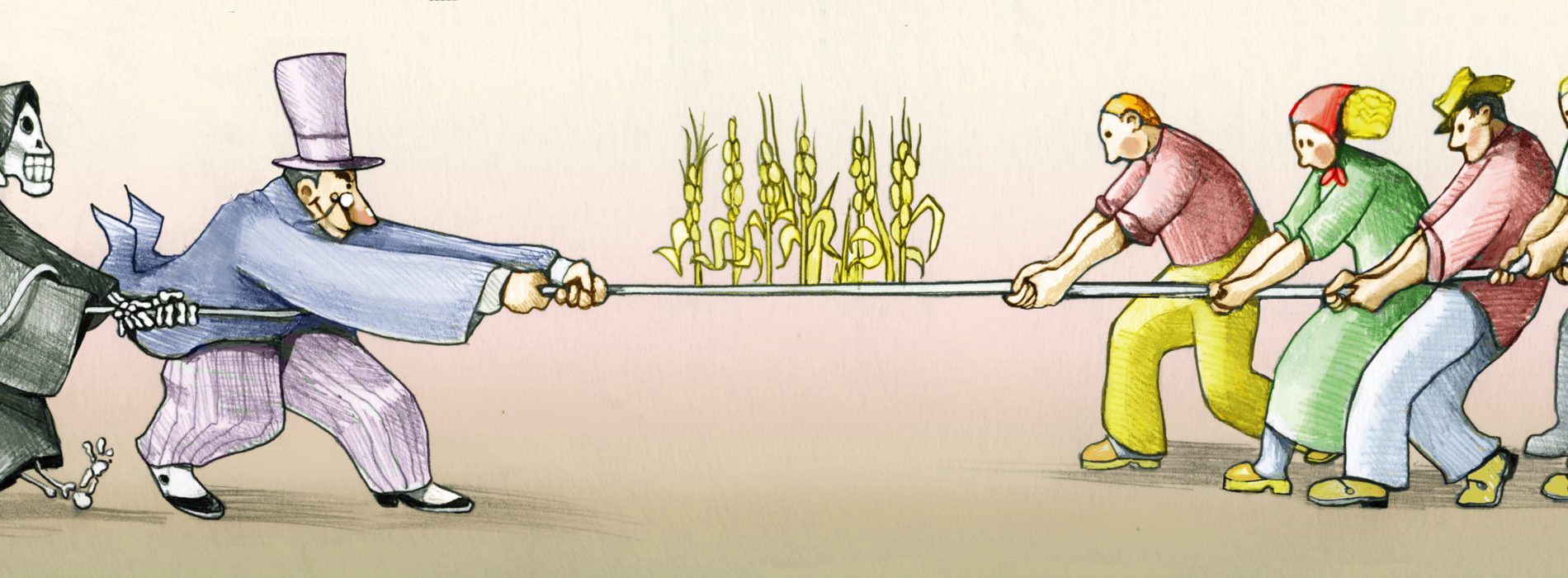

The Act was conceived against the backdrop of organized attempts by lawless individuals and groups to forcibly or fraudulently acquire lands belonging to various entities including government, public sector undertakings, local authorities, religious institutions, and private persons. The legislative intent was to provide a comprehensive legal framework that would ensure speedy disposal of land grabbing cases within six months while offering adequate protection to rightful owners.

Legislative Background and Constitutional Framework

Historical Context and Comparative Analysis

The Gujarat Act draws extensively from similar legislation enacted by other states, yet introduces several unique provisions that have generated considerable legal debate. Unlike the Karnataka Land Grabbing Prohibition Act, 2011, which primarily applies to government lands and lands belonging to wakf, religious institutions, and charitable endowments, the Gujarat Act extends its scope to include private lands as well, making it only the second state after Assam to criminalize land grabbing of private properties [2].

The Andhra Pradesh Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 1982, being the pioneering legislation in this domain, provided the foundational framework that subsequent state enactments have largely followed. However, the Gujarat Act distinguishes itself through its substantially harsher punishment regime, prescribing a minimum sentence of ten years imprisonment compared to Karnataka’s one year and Andhra Pradesh’s six months minimum sentences.

Constitutional Validity and the Doctrine of Pith and Substance

The constitutional validity of the Gujarat Land Grabbing Act faced extensive scrutiny before the Gujarat High Court, with over 150 writ petitions challenging its various provisions. The primary constitutional challenge centered on the argument that the Act encroached upon matters falling under the Concurrent List and Union List of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution of India, thereby requiring Presidential assent under Article 254(1).

In Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave [1], the Gujarat High Court applied the Doctrine of Pith and Substance to determine the true nature and character of the legislation. The Court held that the Act’s paramount purpose and object pertained to activities related to “land” within the meaning of Section 2(c) of the Act, which falls squarely within Entry 18 of List II (State List) of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution. The Court further observed that Entry 64 of List II empowers states to create offenses regarding matters falling within the State List, while Entry 65 allows states to confer jurisdiction and powers to courts regarding any matter in List II.

Definitional Framework and Scope of Application

Key Definitions Under the Gujarat Land Grabbing Act

Section 2 of the Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 2020, provides crucial definitions that determine the Act’s scope and application. The definition of “land grabbing” under Section 2(e) encompasses “every activity of land grabber to occupy or attempt to occupy with or without the use of force, threat, intimidation and deceit, any land (whether belonging to the Government, a Public Sector Undertaking, a local authority, a religious or charitable institution or any other private person) over which he or they have no ownership, title or physical possession, without any lawful entitlement.”

This definition is notably broad and includes various forms of illegal occupation, creation of illegal tenancies, lease or license agreements, unauthorized construction, and sale or hire of such unauthorized structures. The term “land grabber” as defined in Section 2(d) includes not only the primary offender but also those who provide financial aid, collect rent through criminal intimidation, or abet such activities, extending liability to successors-in-interest.

Comparative Definitional Analysis

When compared to similar legislation in other states, the Gujarat Act’s definitions are particularly expansive. The Karnataka Act defines land grabbing more narrowly, focusing primarily on unauthorized occupation without lawful entitlement, while the Andhra Pradesh Act includes similar comprehensive coverage but with less specific provisions regarding financial abetment and successor liability.

Punishment Regime and Proportionality Concerns

Severity of Penalties Under the Gujarat Land Grabbing Act

The Gujarat Land Grabbing Act prescribes one of the most stringent punishment regimes among similar state legislations. Section 4(3) mandates imprisonment for a term not less than ten years but which may extend to fourteen years, along with a fine that may extend to the Jantri value of the properties involved. This represents a significant departure from the more moderate punishment structures adopted by other states.

Section 5 of the Act further criminalizes ancillary activities connected with land grabbing, including selling, allotting, advertising, instigating, or entering into agreements for construction on grabbed land. The punishment for these offenses mirrors that prescribed under Section 4, maintaining the same ten to fourteen-year imprisonment range.

Constitutional Challenge on Grounds of Proportionality

The severe punishment regime faced constitutional challenge on grounds of violating the doctrine of proportionality. Critics argued that the mandatory minimum sentence of ten years was disproportionate to the offense and violated Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. However, the Gujarat High Court in Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave [1] rejected this contention, holding that “the wisdom of legislature must be given due regard and respect, it is for legislation being representative of people to decide as to what is good or bad for them.”

The Court further observed that the punishment could not be challenged on grounds of being harsh and disproportionate, emphasizing judicial restraint in matters of legislative policy where the legislature has made a considered decision based on the gravity of the problem being addressed.

Special Courts and Procedural Framework

Constitution and Jurisdiction of Special Courts

Section 7 of the Act provides for the constitution of Special Courts by the State Government with the concurrence of the Chief Justice of the Gujarat High Court. These courts are presided over by judges appointed with similar concurrence, who must have previously served as Sessions Judges or District Judges. The tenure of Special Court judges is limited to three years, subject to reconstitution or abolition of the court.

The procedural framework established under Section 9 grants Special Courts extensive powers to take cognizance either suo moto or on application by any person or authorized officer. Significantly, Section 9(2) provides that the decision of the Special Court shall be final, effectively ousting the jurisdiction of other courts and limiting appellate remedies to constitutional writ jurisdiction.

Blending of Civil and Criminal Proceedings

One of the most controversial aspects of the Gujarat Act is its provision for Special Courts to determine both criminal liability and civil questions of title, ownership, and possession. Section 9(5) grants the Special Court discretion to determine the order in which civil and criminal liability should be initiated and whether to deliver decisions before completion of both proceedings.

This blending of civil and criminal proceedings has been criticized as procedurally irregular and potentially violative of established legal principles. The Act allows evidence from criminal proceedings to be used in civil matters while restricting the reverse flow of evidence, creating an asymmetrical evidentiary framework.

Burden of Proof and Reverse Onus Provisions

Section 11 and Constitutional Implications

Section 11 of the Gujarat Act introduces a reverse burden of proof mechanism that has generated significant constitutional debate. Under this provision, once land is alleged to have been grabbed and prima facie proved to belong to the government or a private person, the Special Court must presume that the alleged grabber is indeed a land grabber, with the burden of proving innocence falling on the accused.

This reverse onus provision was challenged as violative of Article 20(3) of the Constitution, which protects against self-incrimination, and the fundamental principle that an accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty. However, the Gujarat High Court in Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave [1] upheld this provision by relying on Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, which requires facts within special knowledge of a person to be proven by that person.

Comparison with Similar Provisions in Other States

The reverse burden provision finds parallel in the Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh Acts, though with varying degrees of stringency. The Karnataka Act includes a similar presumption mechanism, while the Andhra Pradesh Act has comparable provisions but with more procedural safeguards for the accused.

Administrative Framework and Committee Structure

District Collector-led Committee System

Section 12(a) of the Gujarat Act establishes a unique administrative framework requiring prior approval from the District Collector, in consultation with a government-notified committee, before any police officer can record information about offenses under the Act. This committee system, chaired by the District Collector, serves as a preliminary screening mechanism for land grabbing complaints.

The Gujarat High Court in Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave [1] found no constitutional fault with this arrangement, holding that deciding committee membership falls within the executive domain given the varied nature of complaints. However, critics have argued that this system creates an additional bureaucratic layer that may delay justice and provide opportunities for administrative discretion that could be misused.

Investigation and Prosecution Framework

The Act mandates that investigations be conducted only by police officers not below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police, or Assistant Commissioner of Police in areas where a Commissioner of Police is appointed. This high-level investigation requirement aims to ensure proper handling of complex land grabbing cases but may strain police resources and delay investigations.

Conflict with Existing Legal Framework

Interaction with Central Legislation

The Gujarat Act’s relationship with existing central legislation, particularly the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, and Indian Evidence Act, 1872, has been a subject of significant legal scrutiny. Section 15 of the Act contains an overriding provision stating that the Act shall have effect notwithstanding anything inconsistent in any other law.

The Gujarat High Court addressed these concerns in Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave [1], holding that Section 4(1) of the CPC acts as a saving clause permitting special laws to override general procedural provisions. The Court found that the Act’s exclusive jurisdiction provisions for Special Courts were constitutionally permissible and did not create impermissible conflict with central legislation.

Limitation Act and Retrospective Application

One of the most controversial aspects of the Act is its retrospective application, as evidenced by Section 9(1) which allows Special Courts to take cognizance of land grabbing acts “whether before or after the commencement of this Act.” This retrospective criminal liability has been criticized as violative of Article 20(1) of the Constitution, which prohibits ex post facto criminalization.

The Act’s interaction with the Limitation Act, 1963, has also been problematic, as it does not explicitly address limitation periods for land grabbing offenses, potentially creating situations where stale claims could be revived without consideration of normal limitation principles.

Contemporary Legal Challenges and Supreme Court Scrutiny

Pending Supreme Court Appeals

Following the Gujarat High Court’s judgment in Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave [1], several Special Leave Petitions (SLPs) have been filed before the Supreme Court of India challenging the constitutional validity determination. These appeals primarily focus on the issues of disproportionate punishment, reverse burden of proof, and retrospective criminal liability [3].

The Supreme Court’s eventual decision in these matters will have significant implications not only for the Gujarat Act but also for similar legislation in other states, as it will provide authoritative guidance on the constitutional permissibility of stringent anti-land grabbing measures.

Presidential Assent Controversy

An interesting aspect of the constitutional challenge was the argument that the Act required Presidential assent under Article 254(2) of the Constitution due to alleged repugnancy with central laws. The Gujarat High Court definitively rejected this argument, holding that since the Act falls within the State List, no question of Presidential assent arises. This determination has broader implications for state legislative autonomy in matters of land regulation.

Procedural Safeguards and Due Process Concerns

Committee Inquiry Process

The Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Rules, 2020, elaborate on the procedural framework for committee inquiries under Rule 5. The process involves preliminary inquiry by the Collector through designated officers, including police officers when deemed necessary. The committee must conclude inquiries within 21 days and determine whether to direct FIR registration.

While these procedures aim to prevent frivolous complaints, critics argue that they create unnecessary delays and multiple layers of discretionary decision-making that could impede swift justice for legitimate complainants.

Appeal and Review Mechanisms

The Act’s provision making Special Court decisions final, with limited appellate remedies, has been a significant point of criticism. Unlike ordinary civil and criminal proceedings, which have established appellate hierarchies, land grabbing matters under the Gujarat Act can primarily be challenged only through constitutional writ jurisdiction, which has a narrower scope of interference.

This limitation on appeal rights has been defended as necessary for ensuring speedy disposal of cases, but critics argue it violates fundamental principles of natural justice and due process.

Comparative Analysis with Other State Legislation

Karnataka Land Grabbing Prohibition Act, 2011

The Karnataka legislation provides a useful comparative framework for understanding the Gujarat Act’s distinctive features. Key differences include the Karnataka Act’s limitation to government and institutional lands, its more moderate punishment structure (minimum one year imprisonment), and its inclusion of specific procedural safeguards for taking possession of grabbed lands.

The Karnataka Act also provides for both Special Courts and Special Tribunals, with the latter handling cases not taken cognizance of by the former. This bifurcated structure contrasts with Gujarat’s unified Special Court system.

Andhra Pradesh Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 1982

As the pioneering legislation in this field, the Andhra Pradesh Act provides the foundational template that has influenced subsequent state enactments. However, the Gujarat Act departs significantly from the Andhra Pradesh model in several respects, including punishment severity, scope of application to private lands, and procedural complexity.

The Andhra Pradesh Act’s Special Tribunal system, as established under Section 7A, provides for more elaborate procedural safeguards and a more structured approach to case disposal compared to Gujarat’s framework.

Contemporary Relevance and Future Implications

Property Rights Protection in Modern India

The Gujarat Land Grabbing Act represents part of a broader movement toward strengthening property rights protection in contemporary India. As urbanization and development pressures increase, the need for robust legal frameworks to prevent illegal land acquisition has become more pressing.

The Act’s emphasis on protecting both government and private lands reflects evolving understanding of property rights as fundamental to economic development and social stability. However, the balance between strong enforcement measures and constitutional protections remains a subject of ongoing debate.

Implications for Legal Practice

For legal practitioners, the Gujarat Act creates new areas of specialized practice while also presenting significant challenges in terms of procedural complexity and limited appellate options. The Act’s unique features require careful understanding of both substantive provisions and procedural requirements under the Rules.

The integration of civil and criminal proceedings within a single forum presents novel challenges for advocacy and case management, requiring lawyers to develop expertise across traditionally separate areas of practice.

Constitutional Jurisprudence and Fundamental Rights

Article 300A and Property Rights

While the right to property was removed from the list of fundamental rights by the 44th Constitutional Amendment, it remains a constitutional right under Article 300A. The Gujarat Land Grabbing Act serves as an important instrument for protecting this constitutional right, though its methods and procedures must still conform to fundamental rights such as due process under Article 21.

The balance between protecting legitimate property rights and ensuring fair treatment of accused persons represents a continuing tension in the implementation of the Act.

Due Process and Fair Trial Rights

The Act’s procedural innovations, particularly the blending of civil and criminal proceedings and the reverse burden of proof, raise important questions about due process and fair trial rights under Article 21. While the Gujarat High Court has upheld these provisions, their practical implementation continues to generate debate about constitutional compliance.

Conclusion

The Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 2020, represents a bold legislative experiment in property rights protection that has survived significant constitutional challenge. While the Gujarat High Court’s validation in Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave [1] has provided temporary certainty, the pending Supreme Court appeals [3] will ultimately determine the Act’s constitutional fate.

The Act’s stringent approach to land grabbing reflects legitimate concerns about organized land crimes and the need for effective deterrence. However, its procedural innovations and severe punishment regime continue to generate debate about the proper balance between enforcement effectiveness and constitutional protections.

The broader implications of the Gujarat Act extend beyond state boundaries, as it represents a testing ground for innovative approaches to property crime that may influence similar legislation in other jurisdictions. The Supreme Court’s eventual determination of the constitutional challenges will provide crucial guidance for the future development of anti-land grabbing legislation across India.

The Act’s ultimate success will depend not only on its constitutional validity but also on its practical implementation, the development of institutional capacity for enforcement, and the evolution of judicial interpretation of its provisions. As Indian property law continues to evolve in response to contemporary challenges, the Gujarat Land Grabbing Act stands as a significant milestone in the ongoing effort to balance effective enforcement with constitutional governance.

For legal practitioners, property owners, and policy makers, the Act represents both an opportunity and a challenge. Its comprehensive approach to land grabbing offers enhanced protection for legitimate property rights, while its procedural complexities and constitutional questions require careful navigation and ongoing monitoring of judicial developments.

The continuing evolution of this legislative framework will undoubtedly contribute to the broader discourse on property rights, constitutional interpretation, and the role of state legislation in addressing contemporary socio-economic challenges in modern India.

References

[1] Kamlesh Jivanlal Dave & Anr. v. State of Gujarat & Ors, Special Civil Application No. 2995 of 2021, Gujarat High Court, decided on May 9, 2024.

[2] Gujarat High Court: Upholding the validity of The Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 2020. Available at: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e78a6e86-506c-400e-8eff-1e8f9008a9a2

[3] The Constitutionality of the Gujarat Land Grabbing Act of 2020: On Article 254 and the Aftermath. Available at: https://indconlawphil.wordpress.com/2024/06/28/the-constitutionality-of-the-gujarat-land-grabbing-act-of-2020-on-article-254-and-the-aftermath-guest-post/

[4] Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 2020.

[5] Grappling With The Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 2020. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/amp/columns/gujarat-land-grabbing-prohibition-act-2020-cpc-evidence-act-constitution-169607

[6] Andhra Pradesh Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 1982. Available at: https://www.latestlaws.com/bare-acts/state-acts-rules/andhra-pradesh-state-laws/andhra-pradesh-land-grabbing-prohibition-act1982/

Editor: Adv. Aditya Bhatt & Adv. Chandni Joshi

Whatsapp

Whatsapp