Dispute Resolution Panel under Section 144C of the Income Tax Act

Introduction

The Indian taxation framework has witnessed several reforms aimed at reducing litigation and ensuring a faster resolution of disputes, particularly in cases involving international taxation and transfer pricing matters. One significant development in this regard was the introduction of the Dispute Resolution Panel (DRP) under Section 144C of the Income Tax Act, 1961, through the Finance (No. 2) Act of 2009. This mechanism was specifically designed to address the complexities and prolonged litigation associated with assessments involving foreign companies and transfer pricing adjustments. The DRP provides an alternate avenue for dispute resolution that operates outside the traditional appellate process, offering eligible assessees a time-bound mechanism to contest variations proposed by the Assessing Officer before the final assessment is completed. This article examines the legal framework governing the DRP, the procedural aspects, and the evolving jurisprudence surrounding its application.

Legislative Framework and Statutory Provisions

Section 144C was incorporated into the Income Tax Act, 1961, with effect from October 1, 2009[1]. The legislative intent behind this provision was to create a fast-track dispute resolution mechanism that would reduce the burden on appellate forums while ensuring fairness and transparency in the assessment process. According to the statutory scheme, when the Assessing Officer proposes any variation that is prejudicial to the interest of an eligible assessee, the officer must first forward a draft assessment order to such assessee. This requirement ensures that the assessee receives adequate opportunity to contest the proposed variations before the assessment attains finality.

The term “eligible assessee” is defined under sub-section (15) of Section 144C and includes two categories of taxpayers. The first category comprises foreign companies, which are non-resident entities operating in India. The second category includes any person in whose case variations arise as a consequence of an order passed by the Transfer Pricing Officer under sub-section (3) of Section 92CA of the Act[2]. This definition ensures that the DRP mechanism is available to those categories of assessees who typically face complex assessment issues involving international transactions and cross-border taxation matters.

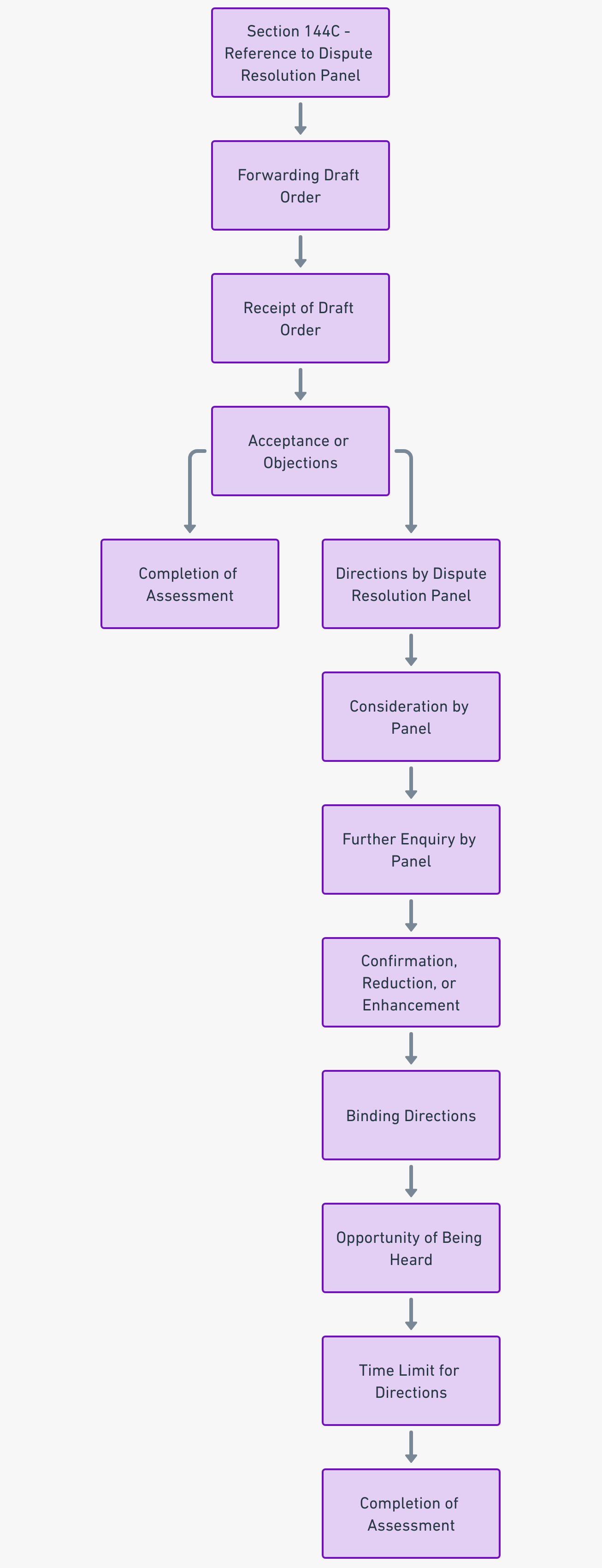

The procedural framework established under Section 144C mandates specific timelines and stages that must be adhered to by both the Assessing Officer and the eligible assessee. Upon receipt of the draft assessment order, the eligible assessee has thirty days to respond. During this period, the assessee may either accept the proposed variations by intimating the Assessing Officer accordingly, or file objections to the variations with both the Dispute Resolution Panel and the Assessing Officer. If the assessee chooses to accept the variations or fails to file objections within the stipulated thirty-day period, the Assessing Officer is required to complete the assessment based on the draft order. This provision streamlines the assessment process in cases where the assessee does not wish to contest the proposed variations.

Composition and Functioning of the Dispute Resolution Panel

The Dispute Resolution Panel is constituted as a collegium comprising three Principal Commissioners or Commissioners of Income-tax, as designated by the Central Board of Direct Taxes. The panel operates as an independent body tasked with evaluating the objections raised by the eligible assessee and issuing directions to the Assessing Officer for completing the assessment. The composition of the panel ensures that the directions issued are the result of collective deliberation among senior tax officials, thereby lending credibility and expertise to the decision-making process.

The DRP is empowered to conduct further inquiries or request additional investigations if it deems such steps necessary before issuing directions. In formulating its directions, the panel must consider various factors including the draft assessment order, the objections filed by the assessee, evidence furnished by the assessee, reports from relevant authorities such as the Transfer Pricing Officer, and any other evidence collected during the proceedings. This holistic approach ensures that the panel’s directions are well-informed and take into account all relevant aspects of the case.

The timelines prescribed for the functioning of the DRP are critical to ensuring expeditious disposal of cases. The panel must issue its directions within nine months from the end of the month in which the draft order is forwarded to the eligible assessee. Upon receiving the directions from the DRP, the Assessing Officer is required to complete the assessment within one month from the end of the month in which the directions are received. These timelines are designed to ensure that assessments involving the DRP are completed in a time-bound manner, thereby providing certainty to the assessee regarding the finalization of their tax liability.

An important feature of the DRP mechanism is that the directions issued by the panel are binding on the Assessing Officer. This means that the Assessing Officer must complete the assessment in accordance with the directions issued by the panel, without any discretion to deviate from such directions. However, the DRP’s powers are limited in certain respects. Notably, the panel cannot set aside any proposed variation or issue directions for further inquiry and reassessment. Instead, the panel can only confirm, reduce, or enhance the variations proposed in the draft assessment order. This limitation ensures that the DRP functions as a dispute resolution mechanism rather than a full-fledged appellate authority.

Procedural Requirements under the Dispute Resolution Panel Rules, 2009

The operational aspects of the DRP are governed by the Income-tax (Dispute Resolution Panel) Rules, 2009, notified vide S.O. No. 2958(E) dated November 20, 2009[3]. These rules provide detailed procedural guidelines for filing objections before the DRP, the constitution of panels at specified locations, and the manner in which the panel conducts its proceedings. The Dispute Resolution Panel rules were framed by the Central Board of Direct Taxes in exercise of the powers conferred under sub-section (14) of Section 144C.

Under Rule 4 of the DRP Rules, objections must be filed in Form No. 35A and submitted to the Secretariat of the panel. The objections must be filed in the English language and presented in paper book form in quadruplicate, accompanied by four copies of the draft assessment order duly authenticated by the eligible assessee or authorized representative. In cases where the draft assessment involves directions issued by the Joint Commissioner under Section 144A or relates to reassessment under Section 147, the objections must also be accompanied by copies of the relevant orders. The rules provide the panel with discretion to accept objections that are not accompanied by all the required documents, ensuring that genuine cases are not dismissed on purely procedural grounds.

The DRP Rules also provide for the constitution of a Secretariat for each panel, which is responsible for receiving objections, correspondence, and other documents filed by the eligible assessee. The Secretariat also issues notices, correspondence, and directions on behalf of the panel. This administrative framework ensures that the proceedings before the DRP are conducted in an organized and systematic manner.

Dispute Resolution Panels have been constituted at specified locations across India, including major metropolitan cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Pune, Kolkata, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, Bangalore, and Chennai[4]. This geographical distribution ensures that eligible assessees across different regions have access to the DRP mechanism without having to travel long distances. Each panel comprises three Commissioners or Directors of Income-tax who perform these duties in addition to their regular functions.

Optional Nature of the DRP Mechanism

A critical aspect of the DRP framework is that it provides an optional remedy to eligible assessees. The Central Board of Direct Taxes has clarified through its circulars that the assessee has the choice to either file objections before the DRP or pursue the normal appellate channel by filing an appeal before the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals)[5]. This optional nature ensures that assessees are not compelled to approach the DRP and can instead opt for the traditional appellate route if they so prefer.

The choice between approaching the DRP and filing an appeal before the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals) is an important strategic decision for the assessee. While the DRP offers a time-bound mechanism with directions that are binding on the Assessing Officer, it does not provide a personal hearing opportunity after the directions are issued. In contrast, the appellate process before the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals) provides the assessee with multiple opportunities for personal hearings and a more detailed consideration of the facts and legal issues involved. The assessee must therefore weigh these factors carefully before deciding which avenue to pursue.

It is important to note that once the assessee chooses to file objections before the DRP, the normal appellate route is foreclosed. The assessee cannot subsequently withdraw the objections and file an appeal before the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals). This ensures that there is no duplication of proceedings and that the choice made by the assessee is final and binding.

Judicial Interpretation and Case Law

The application and interpretation of Section 144C have been the subject of judicial scrutiny in several cases before various courts and tribunals. One of the most significant issues that has arisen relates to the interplay between the timelines prescribed under Section 144C and the general limitation period for completing assessments under Section 153 of the Income Tax Act.

In the recent case of Assistant Commissioner of Income Tax & Ors. v. Shelf Drilling Ron Tappmeyer Limited (2025), the Supreme Court of India delivered a split verdict on whether the twelve-month outer time limit under Section 153 of the Income Tax Act applies to proceedings under Section 144C involving eligible assessees[6]. The case arose from appeals filed by the Income Tax Department challenging a Bombay High Court decision that held final assessment orders passed after the Section 153(3) limitation period were time-barred. The respondent in this case was a foreign entity providing offshore drilling services in India for the assessment year 2014-15. The Income Tax Appellate Tribunal had remanded the case to the Assessing Officer for fresh adjudication on October 4, 2019. Under Section 153(3), the Assessing Officer had twelve months from the end of the financial year to pass a fresh assessment order, which was initially March 31, 2021, and later extended to September 30, 2021 due to COVID-19 relaxations. The Assessing Officer issued a draft assessment order on September 28, 2021, just before the extended deadline, but no final assessment order was passed before September 30, 2021.

Justice B.V. Nagarathna held that while Section 144C prescribes self-contained procedures for eligible assessees, the overall limitation period under Section 153(3) continues to apply. According to this view, all procedures under Section 144C, including the issuance of the draft order, consideration by the DRP, and passing of the final assessment order, must be completed within the existing twelve-month limitation period prescribed under Section 153(3). Justice Nagarathna reasoned that Parliament has consistently reduced assessment timelines to ensure speedy completion and certainty, and allowing the DRP process to operate outside Section 153 would defeat that objective.

In contrast, Justice Satish Chandra Sharma held that specific timelines under Section 144C operate independently of Section 153(3), and the High Court erred in quashing assessments on limitation grounds. Justice Sharma reasoned that Parliament, through non-obstante clauses in sub-sections (4) and (13) of Section 144C, intended to exclude Section 153’s outer limit for DRP cases. He emphasized that if the entire procedure prescribed under Section 144C were to be subsumed within the overall time period prescribed under Section 153, it would result in a complete catastrophe for recovering lost tax revenue[7]. The Court emphasized that timelines under Section 144C are independent and operate in addition to Section 153 timelines, with final assessment orders required within one month of draft orders or within eleven months if objections are filed before the DRP.

The split verdict in the Shelf Drilling case has significant implications for the functioning of the DRP mechanism. Since the two judges could not agree on the interpretation of the limitation provisions, the matter will now need to be referred to a larger bench of the Supreme Court for authoritative determination. Until such determination is made, there remains uncertainty regarding whether the DRP timelines operate within or in addition to the Section 153 limitation period.

Directions and Powers of the Dispute Resolution Panel

The scope of the DRP’s powers in issuing directions is an important aspect of the mechanism. Under the statutory framework, the DRP can confirm, reduce, or enhance the variations proposed in the draft assessment order. However, as noted earlier, the panel cannot set aside any proposed variation or direct the Assessing Officer to conduct further inquiry before passing the assessment order. This limitation on the DRP’s powers has been the subject of discussion among tax practitioners and has been upheld by various tribunal decisions.

The binding nature of DRP directions on the Assessing Officer ensures that the panel’s determinations are given effect without further deliberation. However, this also means that if the assessee is aggrieved by the directions issued by the DRP, the only recourse available is to file an appeal before the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal after the final assessment order is passed by the Assessing Officer in accordance with the DRP’s directions. The assessee cannot challenge the DRP’s directions directly before any appellate forum, as the directions themselves do not constitute a final order for the purposes of appeal.

The DRP is required to provide an opportunity of being heard to both the assessee and the Assessing Officer before issuing directions that are prejudicial to either party. This ensures that principles of natural justice are followed and that both sides have an opportunity to present their case before the panel. However, it is important to note that once the DRP issues its directions, no further opportunity of hearing is provided to the assessee. The Assessing Officer must simply give effect to the directions and pass the final assessment order accordingly.

Integration with Faceless Assessment Scheme

With the introduction of the faceless assessment scheme under Section 144B of the Income Tax Act through the Finance Act, 2020, the Dispute Resolution Panel mechanism has been integrated into the faceless assessment framework. Under the faceless assessment scheme, assessments are conducted electronically without face-to-face interactions between the Assessing Officer and the assessee. The integration of Section 144C with Section 144B ensures that eligible assessees can benefit from both the faceless assessment process and the Dispute Resolution Panel mechanism.

Under the integrated framework, when a draft assessment order is prepared in a faceless assessment and involves an eligible assessee, the draft order is forwarded to the assessee through the National Faceless Assessment Centre. The assessee can then file objections before the DRP electronically, and the panel conducts its proceedings without requiring physical presence. This integration represents a significant advancement in the use of technology for tax administration and dispute resolution, ensuring that assessments are conducted in a transparent and efficient manner while minimizing opportunities for corruption and harassment.

The faceless assessment scheme has prescribed detailed procedures for various stages of assessment, including the role of assessment units, verification units, technical units, and review units. When an assessment involves an eligible assessee under Section 144C, the National Faceless Assessment Centre coordinates with the Dispute Resolution Panel to ensure that the timelines and procedures prescribed under both Section 144B and Section 144C are followed. This coordination ensures that the benefits of both the faceless system and the DRP mechanism are made available to eligible assessees.

Benefits and Limitations of the DRP Mechanism

The DRP mechanism offers several advantages to eligible assessees, particularly in cases involving complex transfer pricing adjustments and international taxation matters. The primary benefit is the availability of a time-bound resolution mechanism that operates faster than the traditional appellate process. The fact that the DRP must issue its directions within nine months, and the Assessing Officer must complete the assessment within one month thereafter, ensures that cases are disposed of expeditiously. This reduces the period of uncertainty for assessees regarding their tax liabilities and enables them to plan their financial affairs more effectively.

Another significant advantage is that the DRP comprises three senior tax officials who collectively deliberate on the issues raised by the assessee. This collegium approach ensures that the directions issued are the result of careful consideration by experienced tax administrators who bring their expertise to bear on complex matters. The binding nature of the DRP’s directions on the Assessing Officer also provides assurance to the assessee that the panel’s determinations will be implemented without further dispute at the assessment stage.

However, the DRP mechanism also has certain limitations that must be acknowledged. The most significant limitation is that the panel cannot set aside proposed variations or direct further inquiry. This means that if the assessee’s case requires additional investigation or examination of new evidence, the DRP cannot accommodate such requirements. In such situations, the traditional appellate route before the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals) may be more appropriate, as the appellate authority has wider powers to set aside the assessment and remand matters for fresh consideration.

Another limitation is the lack of a personal hearing opportunity after the DRP issues its directions. While the panel must provide an opportunity of being heard before issuing directions, once the directions are issued, the Assessing Officer must implement them without any further opportunity for the assessee to present arguments. This contrasts with the appellate process, where multiple opportunities for hearing are typically provided.

The split verdict in the Shelf Drilling case has also highlighted the uncertainty surrounding the interaction between DRP timelines and general limitation provisions. Until this issue is authoritatively resolved by a larger bench of the Supreme Court, there remains a degree of unpredictability regarding whether assessments completed through the DRP mechanism are vulnerable to being challenged as time-barred.

Conclusion

The Dispute Resolution Panel under Section 144C represents a significant innovation in the Indian taxation framework, providing eligible assessees with an expeditious and effective mechanism for resolving disputes arising from draft assessment orders. The mechanism has been particularly beneficial in cases involving foreign companies and transfer pricing adjustments, where complex issues of international taxation require expert consideration. The binding nature of DRP directions, combined with the time-bound framework for disposal of cases, has contributed to reducing litigation and providing greater certainty to taxpayers.

However, the recent split verdict in the Shelf Drilling case has brought to the fore important questions regarding the interplay between DRP timelines and general limitation provisions under the Income Tax Act. The resolution of this issue by a larger bench will be crucial in determining the future trajectory of the DRP mechanism and ensuring clarity for both taxpayers and tax administrators. Despite these challenges, the DRP continues to serve as an important tool in the government’s efforts to create a more taxpayer-friendly and efficient tax administration system.

The success of the DRP mechanism in reducing appeals and expediting case disposal demonstrates the value of specialized dispute resolution mechanisms in the taxation context. As the Indian tax system continues to evolve with increasing cross-border transactions and complex international tax issues, the role of the DRP is likely to become even more significant. Future refinements to the mechanism, based on practical experience and judicial interpretation, will further enhance its effectiveness as a dispute resolution tool that balances the interests of revenue protection with taxpayer rights and procedural fairness.

References

[1] Income-tax (Dispute Resolution Panel) Rules, 2009. Notification No. S.O. 2958(E), dated 20-11-2009. Available at: https://itatonline.org/info/income-tax-dispute-resolution-panel-rules-2009/

[2] Income Tax Act, 1961. Section 144C – Reference to Dispute Resolution Panel. Available at: https://www.aaptaxlaw.com/income-tax-act/section-144c-income-tax-act-reference-to-dispute-resolution-panel-sec-144c-of-income-tax-act-1961.html

[3] Central Board of Direct Taxes. Notification on Income-tax (Dispute Resolution Panel) Rules, 2009. Available at: https://taxguru.in/income-tax/notification-on-income-tax-dispute-resolution-panel-rules-2009.html

[4] TaxTMI. Section 144C of the Income-tax Act, 1961 – Dispute Resolution Panel (DRP) – Reference to – Constitution of DRP at specified places. Available at: https://www.taxtmi.com/circulars?id=11478

[5] Central Board of Direct Taxes Circular. Clarification regarding filing of Objections before Dispute Resolution Panel. F. No. 142/22/2009-TPL (Pt. II). Available at: https://www.manupatra.com/manufeed/contents/PDF/634003801946558750.pdf

[6] Assistant Commissioner of Income Tax v. Shelf Drilling Ron Tappmeyer Limited, 2025 INSC 946, Civil Appeal Nos. arising from SLP (Civil) Nos. 20569-20572 of 2023. Available at: https://www.barandbench.com/news/litigation/supreme-court-delivers-split-verdict-on-tax-assessment-deadlines-for-foreign-companies

[7] Drishti Judiciary. Section 144C of the Income Tax Act: Supreme Court Split Verdict on Limitation Periods. Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/current-affairs/section-144c-of-the-income-tax-act

[8] Taxmann. Opinion: Interplay of Section 144C(13) and Section 153(3). Available at: https://www.taxmann.com/post/blog/opinion-interplay-of-section-144c13-and-section-1533

[9] Income Tax Appellate Tribunal decisions on Section 144C. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=Section+144C&pagenum=3

Whatsapp

Whatsapp