Hierarchy of Civil Courts in India and Principles of Territorial Jurisdiction under CPC

Introduction to Civil Dispute Resolution Framework

When individuals or entities find themselves unable to resolve disputes through mutual understanding, the civil court system provides an institutional mechanism for adjudication. The process of approaching a court by filing a suit is technically termed as the institution of suit, which initiates formal legal proceedings. The Indian civil justice system operates through a carefully structured hierarchy where each court possesses distinct jurisdictional authority based on both territorial boundaries and the monetary value of disputes. As part of this framework, the principles governing territorial jurisdiction under CPC play a crucial role in determining the appropriate forum for filing a suit. The framework governing these jurisdictional principles is primarily codified in the Civil Procedure Code, 1908, which remains the cornerstone legislation regulating civil litigation in India.[1]

The Hierarchy structure of civil courts ensures that cases are heard at appropriate judicial levels, preventing overburdening of higher courts while maintaining accessibility to justice at grassroots levels. This system divides courts into two broad categories: courts of first instance, where cases are initially filed and heard, and appellate courts, which review decisions made by lower courts. The Code establishes clear parameters regarding where suits must be filed, taking into account factors such as the location of property, residence of parties, and the place where the cause of action arose.

The Hierarchy Structure of Civil Courts

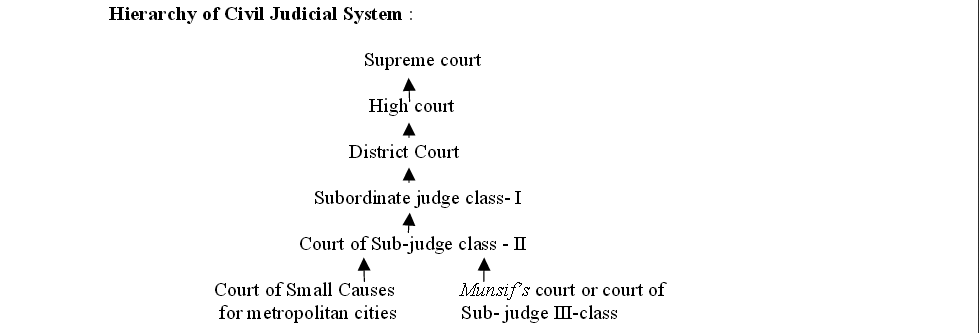

The Indian civil court system follows a three-tier hierarchy structure with the Supreme Court of India positioned at the apex, followed by High Courts at the state level, and subordinate courts operating at district and sub-district levels. The Supreme Court, established on January 28, 1950, exercises appellate, original, and advisory jurisdiction over civil matters of national importance. It comprises the Chief Justice of India and currently 33 other judges appointed by the President.[2] All courts throughout India are bound by Supreme Court decisions under Article 141 of the Constitution, which mandates that the law declared by the Supreme Court shall be binding on all courts within the territory of India.

High Courts function as the principal judicial authority at the state level, with 25 High Courts currently operational across India. These courts exercise supervisory jurisdiction over all subordinate courts within their territorial limits and possess both original and appellate jurisdiction. High Courts hear appeals from district courts and can issue writs for enforcement of fundamental rights under Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution. Below the High Courts, the subordinate court system comprises District Courts, which are the highest courts at the district level. District Judges preside over these courts, handling significant civil disputes including property matters, contract breaches, and matrimonial issues. The District Court structure further includes Sub-Judge Courts, which typically handle matters where the subject matter value exceeds one lakh rupees, and Munsif Courts, which represent the lowest tier and handle suits within specified pecuniary limits.[3]

Fundamental Principle of Court Competency

Section 15 of the Civil Procedure Code establishes the foundational principle that “every suit shall be instituted in the Court of the lowest grade competent to try it.” This provision ensures efficient distribution of judicial workload by requiring plaintiffs to approach the appropriate level of court based on the nature and value of their claim. The rationale behind this requirement is to prevent higher courts from being burdened with matters that can be adequately addressed by courts of lower grade, thereby preserving judicial resources for complex or high-value disputes requiring senior judicial consideration.[4]

The competency of a court to try a suit depends on two critical factors: pecuniary jurisdiction, which refers to the monetary limits within which a court can entertain cases, and territorial jurisdiction, which defines the geographical area over which a court exercises authority. While pecuniary limits vary from state to state based on local legislation, territorial jurisdiction follows uniform principles laid down in the CPC. The Supreme Court in Kiran Singh v. Chaman Paswan observed that jurisdiction under Section 15 is determined by the plaintiff’s valuation stated in the plaint, not the amount for which a decree is ultimately passed, emphasizing that plaintiffs have the right to determine the value of relief sought, which should not be considered arbitrary unless manifestly unreasonable.

Territorial Jurisdiction Under CPC for Immovable Property Disputes

Section 16 of the Civil Procedure Code embodies the well-established maxim that actions concerning immovable property must be brought in the forum where such property is situated. This provision applies to six specific categories of suits: recovery of immovable property with or without rent or profits, partition of immovable property, foreclosure, sale or redemption in cases involving mortgages or charges upon immovable property, determination of any other right to or interest in immovable property, compensation for wrongs to immovable property, and recovery of immovable property under distraint or attachment. The underlying principle recognizes that courts should exercise jurisdiction over property located within their territorial boundaries to ensure effective enforcement of decrees and practical adjudication of property rights.

The proviso to Section 16 creates a limited exception based on the equitable maxim “equity acts in personam,” allowing suits to be filed either where the property is situated or where the defendant resides, carries on business, or personally works for gain, provided the relief sought can be entirely obtained through the defendant’s personal obedience. This exception historically originated from English Chancery Courts’ practice of enforcing judgments through personal processes such as arrest or attachment of the defendant’s property. However, courts have consistently held that this proviso cannot be interpreted to enlarge the scope of the main provision and applies only when the suit falls within one of the categories specified in Section 16 and the relief can be completely obtained through personal compliance.[5]

Landmark Judicial Interpretation: The Harshad Chiman Lal Modi Case

The Supreme Court’s decision in Harshad Chiman Lal Modi v. DLF Universal Ltd. (2005) 7 SCC 791 provides authoritative guidance on jurisdictional principles governing suits relating to immovable property. In this case, the appellant entered into a plot buyer agreement with DLF Universal Limited for purchasing residential property situated in Gurgaon, Haryana. Although the agreement was executed in Delhi, payments were made in Delhi, and the agreement contained a clause conferring jurisdiction on the Delhi High Court, the Supreme Court held that the Delhi court lacked jurisdiction to entertain the suit. The Court emphasized that Section 16 establishes a mandatory rule that suits for specific performance of agreements relating to immovable property must be instituted where the property is located, regardless of where the contract was executed or where the parties reside.[6]

The Court observed that Section 16 of CPC recognizes the fundamental principle that a court within whose territorial jurisdiction immovable property is not situated has no power to deal with and decide rights or interests in such property. Furthermore, the Court held that where suits are governed by Section 16, contractual clauses conferring jurisdiction on particular courts cannot override the statutory mandate. Section 20, which allows parties to agree on jurisdiction, applies only where two or more courts have concurrent jurisdiction, not in situations where Section 16 exclusively determines the competent forum. This landmark judgment reinforces the primacy of the situs of immovable property in determining territorial jurisdiction and clarifies that parties cannot confer jurisdiction upon courts that lack it under law through private agreements.

Jurisdiction for Property Situated Across Multiple Districts

Section 17 of the Civil Procedure Code addresses situations where immovable property subject to dispute is situated within the jurisdiction of different courts. This provision allows a suit to be instituted in any court within whose local limits any portion of the property is situated. However, a critical proviso requires that the entire claim must be cognizable by the chosen court in terms of pecuniary jurisdiction. This means that while territorial jurisdiction can be satisfied by the presence of any portion of the property within a court’s limits, the court must possess adequate pecuniary jurisdiction to handle the total value of the subject matter in dispute.

For illustration, if four brothers seek partition of ancestral property located across three districts, and the total property value exceeds the pecuniary limit of courts in one district, the suit cannot be filed there despite a portion of the property being situated within that jurisdiction. The plaintiff must approach a court that satisfies both requirements: having territorial jurisdiction over at least a portion of the property and possessing pecuniary jurisdiction over the entire property value. This provision balances convenience for plaintiffs with ensuring that cases are heard by courts with appropriate jurisdictional capacity.

Suits Relating to Wrongs Against Persons and Movable Property

Section 19 of the Civil Procedure Code governs territorial jurisdiction for suits seeking compensation for wrongs to persons or movable property, encompassing tortious liability claims such as negligence, nuisance, defamation, trespass, and personal injury arising from accidents. This provision grants plaintiffs an option to file suits either where the wrong was committed or where the defendant resides, carries on business, or personally works for gain. The flexibility provided under this section recognizes that in tort cases, both the place where the wrongful act occurred and the defendant’s location have legitimate connections to the dispute, and plaintiffs should have the choice to pursue remedies in the more convenient or strategically advantageous forum.[7]

Courts have interpreted this provision to ensure that the cause of action genuinely has territorial connection with the chosen forum. The determination of where a wrong was committed depends on factual circumstances of each case. For instance, in cases involving vehicular accidents, the place where the accident occurred would typically constitute the place where the wrong was committed. Similarly, in defamation cases, both the place where defamatory material was published and where it was received may constitute relevant territorial connections. The option provided under Section 19 is subject to pecuniary jurisdiction requirements, ensuring that the chosen court has authority to award the quantum of damages claimed.

General Jurisdictional Principles Under Section 20

Section 20 of the Civil Procedure Code functions as a residuary provision covering all suits not specifically addressed by Sections 16 through 19. The Supreme Court in Harshad Chiman Lal Modi v. DLF Universal Ltd. confirmed that Section 20 leaves no room for doubt that it is a residuary provision applicable only to cases falling outside the scope of preceding sections. Under Section 20 of CPC, suits can be instituted in courts within whose territorial jurisdiction the defendant actually and voluntarily resides, carries on business, or personally works for gain at the time of commencement of the suit, or where the cause of action, wholly or in part, arises.[8]

The concept of cause of action holds particular significance under Section 20. Cause of action is defined as every fact which, if traversed, it would be necessary for the plaintiff to prove in order to support the right to judgment. The Supreme Court in Oil and Natural Gas Commission v. Utpal Kumar Basu explained that cause of action constitutes the bundle of essential facts integral to a claim, as determined by averments made in the plaint. Importantly, cause of action may arise at multiple locations, and Section 20(c) explicitly permits suit institution where cause of action arises wholly or in part. However, the facts relied upon must genuinely constitute part of the cause of action and not be merely incidental or insignificant circumstances.

When multiple defendants reside in different jurisdictions, Section 20 presents specific considerations. The general rule requires filing separate suits where each defendant resides, which often proves impractical and expensive. As an alternative, plaintiffs may file a single suit where any one defendant resides, provided either the court grants leave for such institution or the other defendants who do not reside within that jurisdiction acquiesce to such institution. The most practical approach typically involves filing suit where the cause of action arose, as this allows joinder of all defendants regardless of their respective residences. The Explanation to Section 20 clarifies that corporations are deemed to carry on business at their sole or principal office in India, or with respect to causes of action arising at locations with subordinate offices, at such places.

Waiver and Objections to Jurisdiction

Section 21 of the CPC recognizes that objections regarding territorial or pecuniary jurisdiction may be waived by parties. This provision reflects the principle that such jurisdictional defects are not fatal to the validity of proceedings if parties do not raise timely objections. However, objections to territorial and pecuniary jurisdiction must be taken at the earliest possible opportunity and in any case before or at the time of settlement of issues. The rationale behind permitting waiver is to protect honest litigants from harassment based on technical jurisdictional grounds after substantial proceedings have occurred in good faith. The Supreme Court has emphasized that once a case has been tried on merits and judgment rendered, it should not be subject to reversal solely on technical jurisdictional grounds unless failure of justice has occurred.[9]

In contrast, subject matter jurisdiction relates to the inherent authority of a court to hear particular types of cases and cannot be conferred by consent or waived by parties. Where a court lacks subject matter jurisdiction, any order passed would be a nullity regardless of parties’ conduct or passage of time. The distinction between subject matter jurisdiction and territorial or pecuniary jurisdiction has significant practical implications. Courts have held that neither acquiescence nor express consent of parties can confer jurisdiction upon a court if statutory limitations bar its authority to entertain particular claims. This principle ensures that the statutory scheme governing distribution of judicial business is not undermined by private agreements or procedural defaults.

Critical Considerations in Determining Place of Suing

Several overarching principles emerge from the statutory provisions and judicial interpretations governing territorial jurisdiction under CPC. First, the place of residence of the plaintiff is uniformly immaterial across all categories of suits. Plaintiffs cannot file suits exclusively based on their own residence or convenience, as this would enable potential abuse through forum shopping and harassment of defendants. The Code consistently requires either connection to the property location, defendant’s residence, or place where cause of action arose. Second, where uncertainty exists regarding local limits of jurisdiction, Section 18 provides that suits may be instituted in any court having jurisdiction over the matter if the location is alleged to be uncertain, or alternatively, in the court under whose jurisdiction the defendant resides or business is carried on.

Third, facts pleaded in the plaint must have genuine relevance to the dispute to establish cause of action for jurisdictional purposes. Courts have held that facts having no bearing on the actual dispute do not confer territorial jurisdiction. The Union of India v. Adani Exports Ltd. judgment clarified that facts pleaded must have relevance to the lis or controversy involved in the case to constitute part of cause of action. Finally, exclusive jurisdiction clauses in agreements may be given effect only when they relate to situations where multiple courts have concurrent jurisdiction under the Code. Such clauses cannot override mandatory provisions like Section 16, which exclusively determines competent forums for certain categories of disputes regardless of contractual stipulations.

Practical Application and Strategic Considerations

Understanding jurisdictional principles has significant practical implications for litigants and legal practitioners. When contemplating institution of suit, plaintiffs must carefully analyze the nature of the dispute to determine which provision of the Code applies. For property-related disputes falling under Section 16, the location of immovable property conclusively determines jurisdiction, leaving no room for alternative forums regardless of other connections to different jurisdictions. Where multiple defendants are involved and reside in different locations, strategic decisions must be made regarding whether to pursue multiple suits in different jurisdictions or to consolidate claims by filing where cause of action arose or where one defendant resides with appropriate permissions.

The timing of jurisdictional objections also carries strategic significance. Defendants wishing to challenge territorial or pecuniary jurisdiction must do so promptly, typically in the written statement or before settlement of issues. Delayed objections may be deemed waived, precluding later challenges even if the court lacked proper jurisdiction initially. Conversely, plaintiffs must ensure that chosen forums possess all required jurisdictional elements to avoid dismissals after substantial time and resources have been invested in litigation. The Harshad Chiman Lal Modi case illustrates the consequences of jurisdictional errors, where despite eight years of proceedings and completion of evidence, the suit was ordered to be returned for presentation to the proper court, requiring the litigation to restart entirely in the correct jurisdiction.

Conclusion

The Civil Procedure Code (CPC) establishes a carefully calibrated framework governing territorial jurisdiction and court hierarchy designed to ensure efficient administration of justice while maintaining accessibility and fairness. The Hierarchy structure, spanning from the Supreme Court to subordinate courts at district and sub-district levels, provides multiple tiers of adjudication while preserving appellate remedies. Jurisdictional provisions contained in Sections 15 through 21 create clear rules determining proper forums for different categories of civil disputes, balancing considerations of convenience, connection to the dispute, and effective enforcement of judicial decrees. Judicial interpretations, particularly landmark decisions like Harshad Chiman Lal Modi v. DLF Universal Ltd., have clarified ambiguities and reinforced the primacy of statutory mandates over contractual arrangements in jurisdictional matters. Mastery of these principles remains essential for legal practitioners and litigants seeking to navigate the civil justice system effectively and avoid costly procedural errors that may derail substantive claims. As the civil court system continues to evolve through legislative amendments and judicial interpretations, these foundational jurisdictional principles remain vital to ensuring orderly, efficient, and accessible civil dispute resolution throughout India.

References

[1] Drishti Judiciary. “Territorial Jurisdiction under Civil Procedure Code, 1908.” Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/ttp-code-of-civil-procedure/territorial-jurisdiction-under-civil-procedure-code-1908

[2] Lexology. “Hierarchy of Courts in India.” (June 27, 2022). Available at: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=49df79a8-4bd4-42a3-b68e-3a753a4eb849

[3] Animal Legal & Historical Center. “Introduction to the Indian Judicial System.” Available at: https://www.animallaw.info/article/introduction-indian-judicial-system

[4] The Law Codes. “Objections to Jurisdiction.” (May 25, 2025). Available at: https://thelawcodes.com/article/objections-to-jurisdiction/

[5] Legalstix Law School. “Territorial Jurisdiction under the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC).” Available at: https://legalstixlawschool.com/blog/Territorial-Jurisdiction-under-the-Code-of-Civil-Procedure-(CPC)

[6] Indian Kanoon. “Harshad Chiman Lal Modi vs. DLF Universal and Anr.” (2005) 7 SCC 791. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1916513/

[7] Law Bhoomi. “Place of Suing in CPC.” (May 9, 2025). Available at: https://lawbhoomi.com/place-of-suing-in-cpc/

[8] CaseMine. “Analysis of Section 20(c) CPC.” (April 7, 2025). Available at: https://www.casemine.com/in/column/analysis-of-section-20(c)-cpc/view

[9] iPleaders. “Place of suing under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908: an insight through case laws.” (November 22, 2021). Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/place-of-suing-under-the-code-of-civil-procedure-1908-an-insight-through-case-laws/

Whatsapp

Whatsapp