Process of Execution of a Will in India: Legal Framework and Requirements

Introduction

The execution of a will represents one of the most critical aspects of succession planning in India, allowing individuals to determine the distribution of their property after death. A will, defined under the Indian Succession Act as a legal declaration of a testator’s intentions regarding their property to take effect after death, must comply with specific statutory requirements to be considered valid and enforceable. The process of executing a will involves intricate legal formalities that ensure the document reflects the true intentions of the testator while preventing fraud, coercion, or undue influence. Understanding these requirements becomes essential for anyone seeking to create a valid testamentary disposition of their estate.

Legal Framework Governing Execution of a Will in India

The primary legislation governing the execution of will in India is the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which consolidated the law applicable to testamentary and intestate succession [1]. This Act applies to all persons except those governed by specific personal laws. The Act distinguishes between privileged and unprivileged wills, each subject to different execution requirements of will in India. Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains are governed by the provisions set out in Part VI of the Act, subject to restrictions and modifications specified in Schedule III. Muslims, however, are not governed by the Indian Succession Act and dispose of their property according to Muslim personal law.

The Act defines fundamental concepts essential to understanding will execution. An executor is a person to whom the execution of the last will of a deceased person is confided by the testator’s appointment. A codicil is an instrument made in relation to a will, explaining, altering, or adding to its dispositions, and is deemed to form part of the will. Probate means the copy of a will certified under the seal of a court of competent jurisdiction with a grant of administration to the estate of the testator.

Capacity to Execute a Will

The capacity to make a will is governed by fundamental principles enshrined in the Indian Succession Act. Every person of sound mind who is not a minor can make a will. The Act provides specific explanations to determine who possesses testamentary capacity. A married woman can dispose of any property by making a will during her lifetime. Persons who are deaf, dumb, or blind are not incapacitated from making a will, provided they understand what they are doing and comprehend the impact the will would have if enforced [2].

An ordinarily insane person may make a will during intervals when they are of sound mind. No person can make a will while in such a state of mind, whether arising from intoxication, illness, or any other cause, that they do not know what they are doing. The testator must possess a competent understanding of the nature of their property, the persons who are kindred to them, and those in whose favor it would be proper to make a will.

The burden of proving testamentary capacity rests on the person propounding the will. In cases where the execution is surrounded by suspicious circumstances, the court scrutinizes the will more carefully. Suspicious circumstances may arise from various factors, including the relationship between the testator and beneficiary, the timing of the will’s execution, or unusual provisions that appear inconsistent with the testator’s known intentions.

Requirements for Execution of Unprivileged Wills

Section 63 of the Indian Succession Act lays down the mandatory requirements for executing an unprivileged will [3]. Every testator, not being a soldier employed in an expedition or engaged in actual warfare, an airman so employed or engaged, or a mariner at sea, must execute their will according to specific rules. The testator must sign or affix their mark to the will, or it may be signed by some other person in their presence and by their direction. The signature or mark of the testator, or the signature of the person signing for them, must be so placed that it appears it was intended thereby to give effect to the writing as a will.

The will must be attested by two or more witnesses, each of whom has seen the testator sign or affix their mark to the will, or has seen some other person sign the will in the presence and by the direction of the testator, or has received from the testator a personal acknowledgment of their signature or mark, or the signature of such other person. Each witness must sign the will in the presence of the testator, but it is not necessary that more than one witness be present at the same time, and no particular form of attestation is necessary.

The recent Supreme Court judgment in Gopal Krishan v. Daulat Ram clarified critical aspects of Section 63 regarding attestation requirements [4]. The Court held that the word “or” in Section 63(c) is disjunctive, meaning it provides alternative methods of attestation rather than cumulative requirements. If an attesting witness testifies that they saw the testator affix their mark on the will, this alone ensures compliance with the section. The requirement of “direction of the testator” only becomes relevant when the witness sees someone other than the testator signing the will on behalf of the testator. This interpretation provides much-needed clarity and prevents valid wills from being invalidated due to overly stringent interpretations of the law.

Privileged Wills and Relaxed Formalities

The Indian Succession Act provides for privileged wills under Section 66, which apply to soldiers employed in an expedition or engaged in actual warfare, airmen so employed or engaged, and mariners at sea [5]. Privileged wills may be in writing or made by word of mouth. The execution of privileged wills is governed by relaxed rules compared to unprivileged wills. The will may be written wholly by the testator with their own hand, in which case it need not be signed or attested. It may be written wholly or in part by another person and signed by the testator, without requiring attestation.

If the instrument purporting to be a will is written wholly or in part by another person and is not signed by the testator, it shall be deemed their will if shown that it was written by the testator’s directions or that they recognized it as their will. If it appears on the face of the instrument that its execution in the manner intended by the testator was not completed, the instrument shall not be invalid by reason of that circumstance, provided the non-execution can be reasonably ascribed to some cause other than abandonment of testamentary intentions.

If the soldier, airman, or mariner has given verbal instructions for preparation of their will in the presence of two witnesses, and these have been reduced to writing in their lifetime but they died before the instrument could be prepared and executed, such instructions shall be considered to constitute their will, even if not reduced to writing in their presence or read over to them. The testator may make a will by word of mouth by declaring their intentions before two witnesses present at the same time.

Attestation Requirements and Recent Jurisprudence

The attestation of a will serves as a crucial safeguard against fraud and ensures that the document truly reflects the testator’s intentions. Attestation must be performed by at least two witnesses who are present at the time of the testator’s signing and who possess the animus attestandi, meaning the intention to attest the document as a will. The witnesses must sign the will in the presence of the testator, though they need not all be present simultaneously.

The proof of a will requires examination of at least one attesting witness if alive and subject to the process of the court, as mandated by Section 68 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. The propounder of a will must prove that it was duly and validly executed, not merely by proving the testator’s signature but also by proving that attestations were made in the manner and form required by Section 63(c) of the Indian Succession Act.

Recent judicial pronouncements have reinforced that mere registration of a will does not automatically establish its validity [6]. The Supreme Court has consistently held that for a will to be proved as genuine, it must comply with requirements prescribed in the Indian Evidence Act and the Indian Succession Act. Registration may provide additional security and minimize disputes, but it cannot substitute for proper execution and attestation as required by law.

Revocation, Alteration, and Revival of Wills

A will is liable to be revoked or altered by the maker at any time when they are competent to dispose of their property by will. The Indian Succession Act provides specific mechanisms for revocation. A privileged will or codicil may be revoked by the testator through an unprivileged will or codicil, or by any act expressing an intention to revoke it accompanied by formalities sufficient to give validity to a privileged will, or by burning, tearing, or otherwise destroying the same by the testator or by some person in their presence and by their direction with the intention of revoking it.

No obliteration, interlineation, or other alteration made in any unprivileged will after its execution shall have any effect, except insofar as the words or meaning of the will have been rendered illegible or undiscernible, unless such alteration has been executed in the manner required for execution of the will. The will as so altered shall be deemed duly executed if the signature of the testator and subscription of the witnesses is made in the margin or some other part of the will opposite or near to such alteration, or at the foot or end of or opposite to a memorandum referring to such alteration and written at the end or some other part of the will.

When an unprivileged will has been revoked by the testator, it cannot be revived unless the re-execution is performed according to provisions of the Act and the intention to revoke is evident. However, in situations where a will has been partially revoked and subsequently wholly revoked, at the time of revival of the will, the part initially revoked would not be revived unless an intention to the contrary is shown by such document reviving the will or codicil.

Registration and Probate of Wills

Registration of a will is not mandatory under Indian law, as established by the Supreme Court in Ishwardeo Narain Singh v. Kamta Devi [7]. The Registration Act, 1908, while providing a framework for registration, specifically exempts wills from compulsory registration. Both registered and unregistered wills are equally valid if properly executed according to the Indian Succession Act. However, registration provides certain practical advantages, including safe custody of the will with the registrar, reduced likelihood of successful challenges, and easier acceptance by courts and authorities.

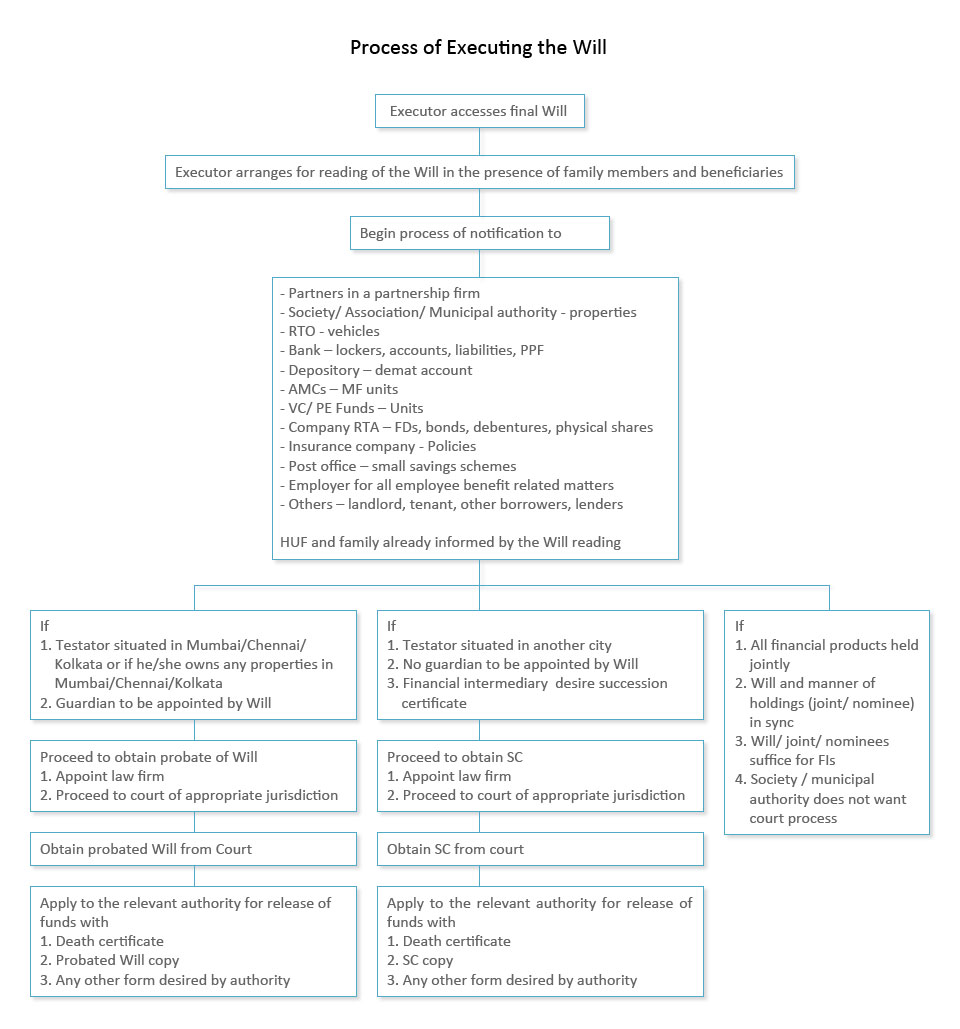

Probate is the legal process through which a will’s validity is certified by a competent authority, typically district courts or high courts. Section 213 of the Indian Succession Act mandates probate in specific circumstances [8]. Probate is compulsory when a will is made by a Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, or Jain within the jurisdiction of the High Courts of Bombay, Madras, or Calcutta, or when the will deals with immovable property situated within these jurisdictions. In all other cases across India, obtaining probate is optional, though advisable when there is probability of the will’s validity being challenged.

The probate process begins when the executor files a petition along with the original will to the district court or high court having appropriate jurisdiction. The petition must include the names and addresses of the deceased’s legal heirs as beneficiaries. The court examines the will’s authenticity, ensures it meets legal requirements, and if satisfied, grants probate. This provides legal authority to executors to distribute assets according to the will’s provisions. Article 137 of the Limitation Act, 1963, provides that petitions for probate should be filed within three years from the death of the testator, though delays can be explained.

Conclusion

The execution of a will in India requires strict compliance with statutory provisions designed to ensure the document genuinely reflects the testator’s intentions while preventing fraud and undue influence. The Indian Succession Act, 1925, provides a well-defined framework distinguishing between privileged and unprivileged wills, each with specific execution requirements. Recent judicial pronouncements, particularly Gopal Krishan v. Daulat Ram, have clarified that attestation requirements should be interpreted according to the plain meaning of statutory language, preventing invalidation of valid wills through overly stringent interpretations. While registration remains optional, it provides practical advantages in terms of preservation and authenticity. Probate, though mandatory only in specific jurisdictions, serves as an important mechanism for validating wills and ensuring proper administration of estates. Understanding these legal requirements enables individuals to create valid testamentary dispositions while minimizing the risk of future disputes among beneficiaries.

References

[1] Indian Succession Act, 1925. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2385

[2] India Filings. (2024). An Overview of Will under Indian Succession Act, 1925. Available at: https://www.indiafilings.com/learn/an-overview-of-will-under-indian-succession-act-1925/

[3] Indian Kanoon. Section 63 in The Indian Succession Act, 1925. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1673132/

[4] Supreme Court of India. (2025). Gopal Krishan & Ors. v. Daulat Ram & Ors., 2025 INSC 18. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/105871119/

[5] Indian Kanoon. Section 66 in The Indian Succession Act, 1925. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1331904/

[6] Lexology. (2023). Supreme Court Reinforces That Mere Registration of A Will Does Not Prove Its Validity. Available at: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=3f941f70-5cbe-4f67-bb87-e0154da33426

[7] Lawyered. Indian Law – Does a Will Need to be Registered Or Not? Available at: https://www.lawyered.in/legal-disrupt/articles/will-registration-mandatory-or-optional/

[8] S.S. Rana & Co. (2025). Probate Process in India: When and Why is it Required? Available at: https://ssrana.in/articles/probate-process-in-india-when-and-why-is-it-required/

Published and Authorized by Sneh Purohit

Whatsapp

Whatsapp