Recovery of Debts Under SARFAESI Act

Introduction

The Indian banking and financial services sector has been instrumental in driving economic growth and facilitating capital formation across various sectors of the economy. However, the pace of legislative reforms governing financial transactions historically lagged behind the rapid evolution of business practices and financial innovations. This legislative gap created significant challenges for financial institutions attempting to recover defaulted loans, leading to a substantial accumulation of non-performing assets that threatened the stability and efficiency of the banking system.

During the 1990s, India’s banking sector faced mounting pressures from rising bad loans and inadequate legal mechanisms for timely debt recovery. The traditional civil litigation process for loan recovery was notoriously slow, often taking years or even decades to reach final resolution. During this protracted period, asset values deteriorated, businesses collapsed, and banks were left holding worthless collateral. This situation not only impaired the financial health of lending institutions but also reduced their capacity to extend fresh credit to productive sectors of the economy, thereby hampering overall economic growth.

Recognizing these systemic challenges, the Government of India initiated comprehensive reforms of the banking and financial sectors. The Narasimham Committee on Financial System in 1991 and the subsequent Narasimham Committee on Banking Sector Reforms in 1998 conducted extensive analyses of the structural problems plaguing Indian banks. These committees identified the absence of effective legal mechanisms for asset recovery as a critical deficiency that needed urgent attention. The Narasimham Committee recommended establishing asset reconstruction companies and empowering banks to enforce securities without lengthy court proceedings.[1]

Building on these recommendations, the Government constituted the Andhyarujina Committee under the chairmanship of T.R. Andhyarujina, a senior Supreme Court advocate and former Solicitor General of India, specifically to examine legal reforms needed for securitization and debt recovery. The committee submitted multiple reports addressing various aspects of financial asset management, with particular emphasis on securitization mechanisms. Based on these comprehensive recommendations, Parliament enacted the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest Act in 2002, commonly known as the SARFAESI Act. This landmark legislation fundamentally transformed the landscape of debt recovery in India by providing banks and financial institutions with powerful tools to address non-performing assets efficiently and expeditiously.

Understanding the SARFAESI Act: Legislative Objectives and Scope

The SARFAESI Act represents a paradigm shift in how Indian law addresses the enforcement of security interests. The full title of the legislation—the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest Act, 2002—reflects its comprehensive approach to tackling the problem of non-performing assets through multiple mechanisms. The Act came into force on June 21, 2002, and has since been amended several times to address emerging challenges and judicial interpretations.

At its core, the SARFAESI Act was designed to achieve several interrelated objectives. First, it aimed to enable banks and financial institutions to realize long-term assets, manage problems of liquidity, and enhance recovery rates on defaulted loans. By providing mechanisms for securitization, the Act allowed lenders to convert illiquid loan assets into tradable securities, thereby improving their liquidity position and freeing up capital for fresh lending. Second, the Act sought to facilitate asset reconstruction by enabling specialized companies to acquire non-performing assets from banks and work toward their revival or optimal realization. Third, and perhaps most significantly, the Act empowered secured creditors to enforce their security interests without the intervention of courts or tribunals, dramatically reducing the time and cost involved in debt recovery.

The SARFAESI Act applies specifically to secured debts—loans or advances backed by collateral in the form of tangible or intangible assets. The legislation defines a secured creditor as any bank or financial institution holding a security interest in the assets of a borrower. This includes scheduled commercial banks operating under the Banking Regulation Act, financial institutions notified under the Act, trustees of debenture holders, and asset reconstruction companies registered with the Reserve Bank of India. The Act’s provisions, however, do not extend to unsecured creditors who lack collateral backing for their loans.

It is important to note certain limitations and exclusions built into the SARFAESI Act. The Act does not apply to security interests in agricultural land, which remain subject to state laws governing such property. Additionally, the enforcement provisions can only be invoked when the outstanding amount, including principal and interest, exceeds specified threshold limits. When the Act was first enacted, this threshold was set at one lakh rupees, though subsequent amendments have revised these limits. The Act also contains special protections for small-scale industries and provides borrowers with opportunities to challenge enforcement actions before the Debt Recovery Tribunal.[2]

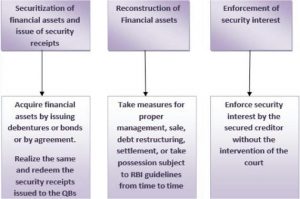

The Three-Pronged Approach: Methods of Debts Recovery Under SARFAESI Act

The SARFAESI Act establishes three distinct but complementary mechanisms through which secured creditors can address non-performing assets. Each method serves different purposes and is appropriate for different situations depending on the nature of the debt, the condition of the borrower’s business, and the creditor’s strategic objectives. These three mechanisms—securitization, asset reconstruction, and enforcement of security interests—together form a comprehensive toolkit that secured creditors can deploy to optimize debt recovery.

Securitization: Transforming Illiquid Assets into Marketable Securities

Securitization represents one of the most innovative features of the SARFAESI Act, introducing sophisticated financial engineering concepts into Indian banking law. Under this mechanism, banks and financial institutions can transfer their financial assets—primarily non-performing loans—to specialized securitization companies. These securitization companies, in turn, pool similar assets together and issue securities backed by the cash flows expected from these underlying assets. These securities, known as security receipts, can then be sold to qualified institutional buyers, providing the originating banks with immediate liquidity.

The Act defines financial assets broadly to encompass various forms of debt and receivables. According to the statutory definition, financial assets include claims on any debt or receivables, whether secured or unsecured, including debts secured by mortgage, charge, hypothecation, or pledge of movable or immovable property. The definition also extends to any right or interest in the security underlying such debts or receivables, whether whole or partial, and any beneficial interest in property or obligations, whether existing, future, accruing, conditional, or contingent.

The securitization process under the SARFAESI Act involves several key steps and stakeholders. When a bank decides to securitize its non-performing assets, it transfers these assets to a securitization company at a negotiated price, typically at a discount reflecting the doubtful nature of the debts. The securitization company then issues security receipts to qualified institutional buyers—entities such as insurance companies, mutual funds, foreign institutional investors, and other sophisticated investors who have the risk appetite and analytical capability to evaluate such investments. The funds raised through the issuance of security receipts provide the securitization company with the capital needed to purchase the financial assets from the originating banks.

Once the securitization company acquires these financial assets, it becomes the owner of the underlying debts and assumes responsibility for their recovery. The company can then employ various strategies to realize these assets, including negotiating with borrowers for settlement, restructuring the debts, enforcing security interests, or even selling the assets to other investors. The returns generated from these recovery efforts are distributed to the holders of security receipts according to the terms of the securities.

This securitization mechanism provides multiple benefits to the banking system. For originating banks, securitization offers an immediate exit from non-performing assets, allowing them to clean up their balance sheets and reduce their reported non-performing asset ratios. The capital recovered through securitization can be redeployed for fresh lending to productive sectors. For the financial system as a whole, securitization creates a secondary market for distressed assets, attracting specialized expertise and capital to the problem of asset recovery. Securitization companies often possess greater expertise and resources for managing and recovering problem loans compared to traditional banks, which primarily focus on lending operations.

Asset Reconstruction: Revival and Restructuring of Distressed Enterprises

Asset reconstruction represents the second major mechanism established under the SARFAESI Act. While securitization focuses primarily on transferring financial assets and distributing risk, asset reconstruction aims at the operational revival and value enhancement of distressed businesses underlying the non-performing assets. Asset reconstruction companies, which can be established under the Act with registration from the Reserve Bank of India, specialize in acquiring non-performing assets from banks and undertaking various measures to rehabilitate the borrower’s business or maximize the value of the underlying security.

The SARFAESI Act, read along with the regulatory guidelines issued by the Reserve Bank of India, provides asset reconstruction companies with a wide range of tools and strategies for managing acquired assets. These companies can take over the management of the borrower’s business operations, bringing in professional management expertise to turn around failing enterprises. In cases where management inefficiency or fraud contributed to the business failure, replacing existing management with competent professionals can sometimes revive the business and restore its profitability.

Asset reconstruction companies can also restructure the borrower’s business by reorganizing operations, divesting non-core assets, renegotiating supplier contracts, or implementing cost-reduction measures. The objective is to restore the business to viability so that it can generate sufficient cash flows to service its debt obligations. In some cases, asset reconstruction may involve selling or leasing portions of the borrower’s business to strategic buyers who can operate those segments more efficiently or integrate them into larger operations.

Financial restructuring forms another critical component of asset reconstruction activities. Asset reconstruction companies can reschedule debt payment obligations, converting short-term liabilities into longer-term debt with more manageable payment schedules. They can also negotiate debt settlements with borrowers, accepting partial payment in full settlement of dues where circumstances warrant such compromises. By offering borrowers realistic repayment plans aligned with their cash flow generation capacity, asset reconstruction companies can often achieve better recovery outcomes than aggressive enforcement actions that destroy business value.

The Act also empowers asset reconstruction companies to enforce security interests over assets acquired from banks. If the borrower continues to default despite restructuring efforts, the asset reconstruction company can proceed to take possession of secured assets and sell them to recover outstanding debts. This enforcement power ensures that borrowers have strong incentives to cooperate with reconstruction efforts and comply with restructured payment obligations.

Asset reconstruction serves important economic functions beyond mere debt recovery. When viable businesses face temporary financial distress due to factors such as economic downturns, sectoral challenges, or temporary liquidity constraints, asset reconstruction can preserve going concerns, maintain employment, and protect stakeholder value. Rather than dismembering businesses through liquidation, asset reconstruction seeks to maximize value through business revival, benefiting not only creditors but also employees, suppliers, and the broader economy.[3]

Enforcement of Security Interests: The Core Mechanism Under Section 13

The enforcement of security interests under Section 13 of the SARFAESI Act constitutes perhaps the most powerful and frequently utilized mechanism available to secured creditors. This provision fundamentally changed the dynamics of secured lending in India by enabling banks and financial institutions to take possession of secured assets and sell them to recover outstanding debts without obtaining court orders or decrees. Prior to the SARFAESI Act, creditors had to file suits in civil courts or approach Debt Recovery Tribunals and await lengthy judicial processes before they could enforce their security interests. The Act eliminated this requirement for judicial intervention, dramatically accelerating the debt recovery process.

Section 13(1) of the SARFAESI Act establishes the fundamental principle that secured creditors can enforce security interests created in their favor without court or tribunal intervention. This provision explicitly states that notwithstanding anything contained in Section 69 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, which traditionally governed the enforcement of mortgages and required judicial processes, security interests under the SARFAESI Act can be enforced in accordance with the provisions of the Act itself.

However, the Act imposes certain prerequisites before secured creditors can invoke enforcement powers. First, the debt in question must be classified as a non-performing asset according to the directions or guidelines issued by the Reserve Bank of India. Generally, this means that the borrower has failed to service the debt—pay interest or principal installments—for a period of ninety days or more. Second, the outstanding amount, including both principal and interest, must exceed the threshold limits specified in the Act. These prerequisites ensure that the powerful enforcement mechanisms are reserved for genuinely defaulted loans of significant value rather than minor payment delays or trivial amounts.

The enforcement process under Section 13 follows a structured sequence designed to balance the creditor’s right to quick recovery with the borrower’s right to notice and opportunity to cure the default. Under Section 13(2), the secured creditor must first issue a written notice to the borrower, requiring payment of the outstanding dues within sixty days from the date of notice. This notice must specify the amount payable, comprising principal, interest, costs, charges, and expenses, along with details of the security interest that will be enforced if payment is not made. The sixty-day period provides borrowers with a reasonable opportunity to arrange funds and discharge their obligations, either through their own resources or by refinancing the debt through other lenders.

Upon receiving the notice under Section 13(2), borrowers face certain immediate restrictions on their ability to deal with the secured assets. Section 13(3) prohibits the borrower from transferring by way of sale, lease, or otherwise the secured assets specified in the notice without prior written consent from the secured creditor. This prohibition prevents borrowers from dissipating assets or transferring them to related parties to defeat the creditor’s security interest. Violations of this provision can result in the transaction being declared void, and the borrower may face penalties under the Act.

If the borrower fails to discharge the outstanding debt within the sixty-day notice period, Section 13(4) empowers the secured creditor to take various enforcement measures. The creditor may take possession of the secured assets, including both movable and immovable property. For immovable property such as land and buildings, the creditor can take physical possession and assume control over the premises. For movable assets like machinery, vehicles, or inventory, the creditor can similarly take custody. The Act provides that the creditor can take possession either directly or by appointing any person authorized by it to take possession on its behalf.

Once in possession of secured assets, the creditor has several options for realization. Under Section 13(4)(a), the creditor can transfer the assets by way of lease, assignment, or sale to realize the secured debt. The Act specifies that any such transfer made by the secured creditor shall be deemed to have been made by the owner of the secured assets, thereby providing clear title to purchasers and preventing subsequent challenges to the validity of the transfer. This provision addresses one of the major impediments to asset sales that existed under the prior legal regime, where purchasers often faced litigation from borrowers challenging the creditor’s authority to sell.

Alternatively, under Section 13(4)(b), the creditor may choose to appoint a manager to manage the secured assets. This option is particularly useful when the assets consist of operational businesses or income-generating properties where preservation of going concern value requires continued management. The appointed manager assumes responsibility for operating the business or managing the property, collecting revenues, paying necessary expenses, and remitting the net proceeds toward discharge of the secured debt.

Section 13(4)(c) provides yet another enforcement option: the creditor may require any person who has acquired any secured assets from the borrower and owes money to the borrower to pay the secured creditor such amounts as may be sufficient to discharge the secured debt. This provision enables creditors to intercept receivables and other amounts payable to the borrower, applying them directly toward debt repayment.

The SARFAESI Act also addresses the situation of joint financing, where multiple creditors have collectively extended credit to a borrower. Section 13(5) mandates that in cases of joint financing, any decision to enforce security interest requires the consent of creditors representing at least seventy-five percent of the total outstanding amount. This provision ensures that a majority of creditors by value can proceed with enforcement even if some minority creditors oppose such action, preventing individual creditors from blocking recovery efforts against the collective interest.

Section 13(8) of the SARFAESI Act embodies an important principle of redemption, providing borrowers with a right to cure defaults and recover their assets even after enforcement proceedings have commenced. This provision states that if at any time before the date fixed for sale or transfer of secured assets, the borrower pays the entire outstanding amount, including all costs, charges, and expenses incurred by the secured creditor, the creditor shall not proceed with the transfer or sale. This redemption right recognizes that borrowers may be able to arrange funds from alternative sources even after enforcement has begun, and the primary objective should be debt recovery rather than asset acquisition. However, this right of redemption expires once the secured assets are actually sold or transferred to third parties, at which point ownership passes to the purchaser and the borrower can no longer reclaim the assets.[4]

Procedural Safeguards and Borrower Protections

While the SARFAESI Act provides powerful enforcement tools to secured creditors, the legislation also incorporates important procedural safeguards and protections for borrowers to prevent abuse and ensure fundamental fairness. These safeguards reflect the constitutional requirement of due process and balance the creditor’s legitimate interest in prompt recovery with the borrower’s right to property and livelihood.

The most significant safeguard is the right of appeal to the Debt Recovery Tribunal provided under Section 17 of the SARFAESI Act. Any person aggrieved by measures taken by the secured creditor under Section 13(4) may file an appeal before the Debt Recovery Tribunal within forty-five days of receiving notice of the measures taken. This appellate mechanism provides borrowers with an opportunity to challenge enforcement actions on various grounds, including questioning whether the debt was indeed a non-performing asset, whether proper procedures were followed, whether the asset valuation was reasonable, or whether the creditor acted in bad faith or in a commercially unreasonable manner.

However, the Act imposes a significant condition on the right of appeal: Section 17(2) requires that the borrower deposit at least seventy-five percent of the amount claimed by the secured creditor before the Debt Recovery Tribunal can entertain the appeal. This deposit requirement serves a dual purpose. First, it ensures that appeals are filed in good faith rather than as delay tactics, since borrowers must commit substantial funds upfront. Second, it provides partial recovery to the creditor even during the pendency of the appeal, reducing the incentive for creditors to take extreme measures. The Debt Recovery Tribunal has discretion to reduce or waive the deposit requirement in appropriate cases, such as where the borrower demonstrates genuine inability to make the deposit despite having a prima facie case on merits.

The Supreme Court of India and various High Courts have interpreted the SARFAESI Act’s provisions in numerous cases, developing a substantial body of jurisprudence that further defines the scope and limitations of enforcement powers. Courts have consistently held that while the Act provides creditors with expedited remedies without court intervention, it does not create unfettered or arbitrary powers. Creditors must comply strictly with statutory procedures, including proper service of notices, accurate calculation of amounts due, and reasonable valuation of secured assets. Failure to comply with these procedural requirements can result in the Debt Recovery Tribunal setting aside enforcement measures.

Courts have also emphasized that secured creditors must act reasonably and in good faith when exercising enforcement powers. For example, when selling secured assets, creditors must endeavor to obtain fair market value and cannot deliberately undersell assets to favor particular buyers. The secured creditor is required to provide proper public notice of sales, allowing interested buyers to participate and bid for the assets. If the sale price is unreasonably low or the sale process was flawed, the Debt Recovery Tribunal can invalidate the sale and order a fresh process.

The Act contains specific protections for certain classes of borrowers. Small-scale industrial undertakings that have outstanding amounts below specified thresholds receive additional protection, with restrictions on the exercise of enforcement powers. The Act also provides that residential properties of borrowers cannot be sold or auctioned if they are exclusively used for residential purposes by the borrower and the family, subject to certain conditions and exemptions.

Furthermore, the limitation period under the Limitation Act, 1963, applies to proceedings under the SARFAESI Act. Section 13(9) clarifies that secured creditors cannot initiate enforcement proceedings if the limitation period for recovery of the debt has expired. Generally, the limitation period for suits on mortgages and other secured loans is twelve years from the date when the right to sue accrues. This limitation period prevents creditors from attempting to enforce very old debts long after the borrower might have reasonably believed the matter was closed.[5]

Regulatory Oversight: The Role of the Reserve Bank of India

The Reserve Bank of India plays a central regulatory role in the operation of the SARFAESI Act, exercising oversight over securitization companies, asset reconstruction companies, and the enforcement of security interests by financial institutions. This regulatory framework ensures that the powerful mechanisms provided under the Act are exercised responsibly and in accordance with sound financial practices.

Under the SARFAESI Act, securitization companies and asset reconstruction companies must register with the Reserve Bank of India before commencing operations. The registration process involves scrutiny of the company’s capital adequacy, management expertise, systems and procedures, and proposed business plan. The Reserve Bank has issued detailed guidelines specifying the minimum net owned fund requirements for registration, which have been periodically revised upward to ensure that only adequately capitalized entities operate in this sector. These capital requirements are essential because asset reconstruction companies deal with high-risk assets and need sufficient financial cushion to absorb potential losses.

The Reserve Bank of India has also issued comprehensive guidelines on the prudential norms applicable to asset reconstruction companies, including norms for income recognition, asset classification, and provisioning for potential losses. These guidelines ensure that asset reconstruction companies maintain realistic assessments of the value of acquired assets and create adequate provisions for assets that may prove unrecoverable. The Reserve Bank conducts periodic inspections of asset reconstruction companies to verify compliance with these norms and takes corrective action where deficiencies are identified.

For banks and financial institutions enforcing security interests under Section 13, the Reserve Bank has issued circulars and guidelines establishing best practices and procedural requirements. These guidelines cover various aspects of the enforcement process, including the issuance of notices, valuation of secured assets, conduct of auctions, and distribution of sale proceeds. Banks are required to establish internal systems and controls to ensure compliance with these guidelines, and the Reserve Bank’s inspection teams verify adherence during regular bank inspections.

The Reserve Bank’s master circulars on debt recovery mechanisms provide detailed instructions on when and how banks should invoke the SARFAESI Act. These circulars emphasize that the SARFAESI mechanism should be used judiciously and not as a first resort for all defaults. Banks are encouraged to first attempt resolution through negotiation, restructuring, or settlement, reserving the SARFAESI enforcement process for cases where other avenues have proven unsuccessful. The Reserve Bank has also issued guidelines requiring banks to follow fair practices in debt collection, prohibiting harassment or coercive tactics against borrowers.

The regulatory framework also addresses the conduct of auctions and sales of secured assets. The Reserve Bank’s guidelines require that auctions be conducted transparently with adequate public notice, allowing sufficient time for potential buyers to inspect assets and submit bids. Reserve prices for auctions must be determined based on proper valuation by qualified valuers, and multiple valuations may be required for high-value assets. These requirements help ensure that assets are sold for fair market value, protecting both the borrower’s interest in maximizing recovery and minimizing deficiency claims, and the creditor’s interest in adequate debt satisfaction.[6]

Critical Analysis: Advantages and Challenges of the SARFAESI Framework

The SARFAESI Act has fundamentally transformed debt recovery in India, providing secured creditors with unprecedented powers to enforce their security interests efficiently. However, more than two decades of experience with the Act has revealed both significant advantages and certain limitations and challenges that merit careful consideration.

Advantages and Positive Impact

The most obvious advantage of the SARFAESI Act is the dramatic reduction in the time required for debt recovery. Prior to the Act, secured creditors had to file suits in civil courts or approach Debt Recovery Tribunals and endure years of litigation before obtaining decrees allowing them to sell secured assets. During this extended period, asset values often deteriorated significantly due to lack of maintenance, obsolescence, or market conditions. By enabling creditors to take possession and sell assets within a matter of months rather than years, the SARFAESI Act has greatly enhanced recovery rates and reduced the economic waste associated with prolonged litigation.

The Act has also changed borrower behavior in positive ways. The knowledge that creditors can quickly enforce security interests has created stronger incentives for borrowers to service their debts regularly and communicate proactively with lenders when facing financial difficulties. This has led to increased voluntary settlements and restructuring agreements, as borrowers recognize that default will trigger swift enforcement action rather than drawn-out court battles. The overall culture of credit discipline has improved, contributing to better financial health of the banking sector.

From a systemic perspective, the SARFAESI Act has enabled banks to clean up their balance sheets more effectively by facilitating the exit of non-performing assets through securitization and asset reconstruction mechanisms. This has freed up capital that banks can deploy for fresh lending to productive sectors, thereby supporting economic growth. The reduction in non-performing assets has also improved the financial stability of banks and enhanced their ability to withstand economic shocks.

The development of a secondary market for distressed assets represents another significant achievement of the SARFAESI framework. Asset reconstruction companies and securitization companies have emerged as specialized players with expertise in managing and recovering problem loans. This specialization has brought greater efficiency to the debt recovery process, as these entities focus exclusively on asset recovery and reconstruction rather than treating it as an ancillary activity to primary lending operations.

Challenges and Areas for Improvement

Despite these advantages, the implementation of the SARFAESI Act has encountered several challenges. One recurring issue concerns the valuation of secured assets, which is critical for determining sale proceeds and calculating deficiency claims. Disputes frequently arise between creditors and borrowers regarding whether assets were sold at fair market value. In a depressed market or for specialized assets with limited buyers, achieving adequate sale prices can be difficult. Some borrowers have alleged that creditors deliberately undersold assets to favor particular buyers or failed to take adequate steps to market assets effectively.

The deposit requirement for filing appeals under Section 17 has been controversial. While intended to prevent frivolous appeals, the requirement to deposit seventy-five percent of the claimed amount before the Debt Recovery Tribunal will hear an appeal effectively denies access to justice for many borrowers who lack liquidity. Even borrowers with legitimate grievances may be unable to pursue appeals if they cannot arrange the substantial deposit required. Courts have grappled with this tension, occasionally reducing or waiving deposits in exceptional circumstances, but the general principle remains that deposits are mandatory.

The Act’s exclusion of unsecured creditors has created situations where secured creditors can quickly seize and sell assets, leaving nothing for unsecured creditors who may have equally valid claims. This has led to a rush among creditors to obtain security interests, and in some cases, to allegations of secured creditors receiving preferential treatment through collusion with borrowers. The interaction between the SARFAESI Act and other insolvency and bankruptcy legislation, particularly the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code enacted in 2016, has also raised complex questions about the coordination of different debt recovery mechanisms.

Implementation issues at the ground level have sometimes undermined the Act’s objectives. Taking physical possession of secured assets can prove difficult when borrowers resist, particularly for immovable property occupied by the borrower or their family. Although the Act provides for assistance from District Magistrates in taking possession, this often requires coordination between banks and local authorities that may not always be forthcoming promptly. In some cases, creditors have faced allegations of using excessive force or improper tactics to obtain possession, leading to public relations problems and regulatory scrutiny.

The treatment of guarantors under the SARFAESI Act presents another area of complexity. While the Act allows creditors to proceed against secured assets, the rights of guarantors who may have provided personal guarantees for the debt are not clearly addressed. Courts have had to interpret how the Act’s provisions apply to guarantors and whether creditors must exhaust remedies against the principal borrower before pursuing guarantors.[7]

Comparative Analysis: SARFAESI and Alternative Debt Recovery Mechanisms

The SARFAESI Act exists alongside other debt recovery mechanisms in Indian law, each with distinct features, procedures, and applicability. Understanding when and how to deploy different mechanisms requires appreciation of their respective strengths and limitations.

The Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993, established Debt Recovery Tribunals as specialized forums for hearing and determining claims by banks and financial institutions for recovery of debts. Unlike the SARFAESI Act, which provides a non-judicial enforcement mechanism, proceedings before Debt Recovery Tribunals are adjudicatory in nature, requiring filing of applications, presentation of evidence, and obtaining orders or decrees. The Debt Recovery Tribunal route is typically slower than SARFAESI enforcement but provides greater opportunity for examination of disputed facts and legal issues. For unsecured debts or where security documentation is questionable, the Debt Recovery Tribunal remains the primary avenue for recovery.

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, introduced a comprehensive framework for resolving corporate insolvency that differs fundamentally from the SARFAESI Act’s creditor-centric enforcement approach. Under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, the focus is on collective resolution of all creditor claims through a committee-driven process aimed at either restructuring the debtor as a going concern or conducting orderly liquidation. The Code imposes an automatic moratorium that stays all enforcement proceedings, including actions under the SARFAESI Act. Once corporate insolvency resolution proceedings are initiated under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, secured creditors cannot independently enforce their security interests but must participate in the collective resolution process. This has created tensions between the two statutes, with courts ruling that the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code prevails due to its non-obstante clause.

The traditional civil litigation route through courts of ordinary jurisdiction remains available for debt recovery but is rarely preferred given the availability of specialized alternatives. Civil suits for specific performance of contracts, declaration of rights, or other relief may occasionally be necessary where issues beyond debt recovery are involved, such as disputes over property ownership or contract interpretation. However, for straightforward debt recovery, the SARFAESI Act or Debt Recovery Tribunal proceedings are generally more efficient.

The choice among these mechanisms depends on multiple factors. For secured creditors with clear documentation and undisputed security interests, the SARFAESI Act provides the fastest route to recovery. Where facts are disputed, documentation is unclear, or the debt is unsecured, Debt Recovery Tribunal proceedings may be more appropriate. For large corporate debtors with multiple creditors and complex financial structures, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code offers a comprehensive framework for addressing all claims collectively. Creditors must carefully evaluate their specific situation and strategic objectives when selecting the appropriate debt recovery mechanism.[8]

Conclusion

The SARFAESI Act has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of secured lending and debt recovery in India. By empowering banks and financial institutions to enforce security interests without court intervention, the Act addressed a critical gap in the legal framework that had previously allowed borrowers to delay repayment indefinitely through protracted litigation. The three mechanisms provided by the Act—securitization, asset reconstruction, and enforcement of security interests—together form a comprehensive toolkit that has enhanced recovery rates, improved credit discipline, and contributed to the stability and efficiency of the Indian banking system.

The enforcement provisions under Section 13 of the SARFAESI Act, in particular, have proven to be powerful tools for debt recovery. The structured process of notice, opportunity to pay, and subsequent enforcement strikes a reasonable balance between protecting creditor rights and providing borrowers with due process. The right of appeal to Debt Recovery Tribunals, despite the deposit requirement, ensures that borrowers have recourse against arbitrary or improper enforcement actions.

However, the implementation experience over the past two decades has also revealed certain challenges and areas where the framework could be strengthened. Issues relating to asset valuation, the high deposit requirement for appeals, coordination with other insolvency mechanisms, and practical difficulties in taking possession of secured assets require ongoing attention from policymakers and regulators. The Reserve Bank of India’s regulatory oversight and periodic refinement of guidelines have been essential in addressing some of these challenges, but further reforms may be necessary to optimize the framework.

Looking forward, the SARFAESI Act will continue to evolve in response to changing financial sector dynamics, judicial interpretations, and lessons learned from implementation. The interplay between the SARFAESI Act and the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code requires careful harmonization to ensure that secured creditors have clarity about their rights and remedies in different situations. Technological innovations, including electronic auction platforms and digital documentation systems, offer opportunities to make SARFAESI enforcement processes more transparent and efficient.

For secured creditors, borrowers, and other stakeholders, understanding the SARFAESI Act’s provisions, procedures, and practical implications remains essential. The Act represents a cornerstone of India’s debt recovery framework and will continue to play a vital role in maintaining the health and efficiency of the financial system. As the Indian economy continues to grow and evolve, the SARFAESI Act must adapt while remaining true to its core purpose: enabling prompt and fair recovery of secured debts while respecting the legitimate rights of all stakeholders.[9]

References

[1] Testbook. “Narasimham Committee 1 & 2: Recommendations & Purpose for Formation.” Available at: https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/narasimham-committee

[2] TaxGuru. “Overview of SARFAESI Act 2002 & Note on process of Enforcement of Security Interest under Section 13.” Available at: https://taxguru.in/corporate-law/overview-sarfaesi-act-2002-note-process-enforcement-security-interest-section-13.html

[3] ClearTax. “SARFAESI ACT, 2002- Applicability, Objectives, Process, Documentation.” Available at: https://cleartax.in/s/sarfaesi-act-2002

[4] Indian Kanoon. “Section 13 in The Securitisation And Reconstruction Of Financial Assets And Enforcement Of Security Interest Act, 2002.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/152603276/

[5] The Legal School. “Section 13 of the SARFAESI Act: Enforcement of Security Interest.” Available at: https://thelegalschool.in/blog/section-13-sarfaesi-act

[6] IBC Laws. “Section 13 of SARFAESI Act, 2002: Enforcement of security interest.” Available at: https://ibclaw.in/section-13-enforcement-of-security-interest/

[7] Wikipedia. “Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002.” Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Securitisation_and_Reconstruction_of_Financial_Assets_and_Enforcement_of_Security_Interest_Act,_2002

Whatsapp

Whatsapp