Comprehensive Guide to the Mutation Process and Village Form No. 6 in Gujarat Land Revenue Administration

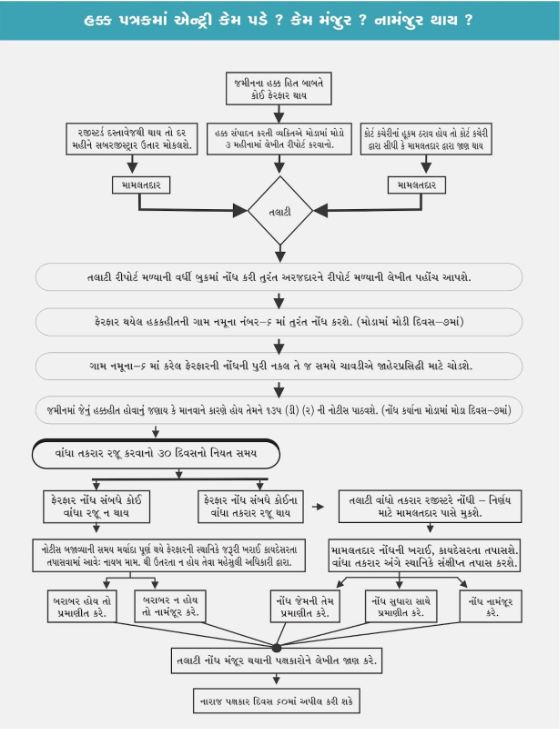

Flowchart of Mutation Process

Understanding the Foundation of Land Ownership Transfers in Gujarat

The process of mutation stands as a fundamental pillar in Gujarat’s land revenue administration system, representing far more than a mere administrative formality. When a property changes hands through sale, inheritance, or any other form of transfer, the mutation process ensures that these changes are officially recognized and recorded in government records. This mechanism protects property rights, maintains transparency in land transactions, and creates a verifiable chain of ownership that can be traced through generations. Village Form No. 6, locally known as HakkPatrak 6, serves as the primary document where these crucial changes are permanently recorded, making it indispensable for anyone involved in land transactions within the state.

The legal framework governing this process finds its roots in the Gujarat Land Revenue Code of 1879,[1] a legislation that has evolved significantly over the decades while maintaining its core principles. This colonial-era legislation, originally enacted as the Bombay Land Revenue Code, has been adapted and amended numerous times to meet contemporary needs while preserving the essential structure of land revenue administration. Understanding this process becomes critical when one considers that improper or incomplete mutation can lead to prolonged legal disputes, cloud the title of property, and create barriers to legitimate ownership rights. The importance of proper mutation extends beyond individual transactions to affect broader economic activities, as clear land titles are prerequisites for obtaining bank loans, government subsidies, and various developmental permissions.

The Historical Context and Legal Framework

The origins of Gujarat’s land revenue system can be traced back to 1879 when the Bombay Land Revenue Code was first enacted. This legislation represented a significant reform in how land records were maintained and how revenue administration was conducted across the Bombay Presidency. The concept of maintaining systematic records of rights, specifically through documents like Village Form No. 6, was first formally considered by the Indian Government in 1897, though the actual implementation took several years. By 1903, a specific law was enacted to establish this record-keeping system, which was subsequently consolidated into the Land Revenue Code in 1913 under Chapter 10.[2]

After Gujarat’s formation as a separate state in 1960, the Bombay Land Revenue Code continued to apply to Gujarat and was eventually renamed the Gujarat Land Revenue Code. The legislation has undergone numerous amendments since then, with significant modifications introduced through the Gujarat Amendment Act of 1987, which substantially revised the procedures for mutation entries and dispute resolution mechanisms. These amendments reflected the changing needs of land administration and incorporated lessons learned from decades of implementation. The Code has been further modernized through various notifications and rules, most notably the Gujarat Land Revenue (Amendment) Rules of 2021 and 2022, which introduced electronic notice procedures and automated mutation processing.[3]

The legal framework established by the Gujarat Land Revenue Code creates a multi-tiered system of land administration. At the village level, the Talati or Village Accountant serves as the primary custodian of land records. The Mamlatdar, appointed under Section 12 of the Code, oversees revenue administration at the taluka level and holds quasi-judicial powers for dispute resolution. The Collector, appointed under Sections 8 and 9, heads the district-level revenue administration and serves as the ultimate appellate authority within the district. Beyond the district level, the Special Secretary Revenue Department handles appeals and exercises supervisory jurisdiction over all revenue matters in the state.

Village Form No. 6: The Chronicle of Land

Village Form No. 6, formally designated as HakkPatrak 6 in Gujarati, functions as the authoritative mutation register maintained at the village level. This document has been aptly described by legal scholars and practitioners as the “horoscope of land” because it provides a complete chronological history of every transaction, transfer, and change affecting a particular piece of land. Just as a horoscope purportedly reveals the past, present, and future of an individual, Village Form No. 6 reveals the complete lineage of land ownership, documenting every transfer, partition, inheritance, and legal encumbrance that has touched the property since independence.

The structure of Village Form No. 6 follows a standardized format prescribed by the Gujarat Land Revenue Rules. Each entry in this register receives a unique serial number, which can range from 1 to 100,000 depending on the volume of transactions in a particular village. These serial numbers serve as permanent identifiers for each mutation entry and are crucial for tracking and verifying the sequence of ownership changes. The register records multiple categories of transactions including sales of land, inheritance through succession, divisions of land among family members, court-ordered transfers, changes mandated by government orders, creation and release of encumbrances related to loans, and various other modifications in land rights and ownership.

The importance of Village Form No. 6 in the legal system cannot be overstated. Courts frequently rely on these records when adjudicating land disputes, and the entries enjoy a presumption of correctness under Section 135J of the Gujarat Land Revenue Code. However, this presumption is rebuttable, meaning that parties can challenge the accuracy of entries by presenting contrary evidence. The register also serves practical purposes beyond legal proceedings. Banks and financial institutions require examination of Village Form No. 6 before sanctioning loans against land as collateral. Prospective purchasers of land must verify the mutation register to ensure that the seller has clear title and that the property is free from disputes or encumbrances.

In the current digital era, Village Form No. 6 has been digitized and made accessible through the AnyRoR (Any Records of Rights Anywhere) portal,[4] a revolutionary step that has transformed access to land records. Citizens can now view the mutation history of any property online without having to physically visit revenue offices. This digitization has enhanced transparency, reduced opportunities for manipulation of records, and empowered property owners and prospective buyers with instant access to crucial information about land ownership.

The Legal Provisions Under Section 135D

Section 135D of the Gujarat Land Revenue Code stands as the cornerstone provision governing the mutation process. The current version of this section, as amended in 1987 and further modified through subsequent rules, establishes detailed procedures that must be followed when recording any change in land ownership or rights. The provision reads, in its substantive part, that “the village accountant shall enter in a register of mutations every report made to him under section 135C or any intimation of acquisition or transfer of any right of the kind mentioned in section 135C received from the Mamlatdar or a Court of Law.”[5]

This seemingly simple directive actually establishes a comprehensive framework for mutation administration. The section requires that whenever the village accountant makes an entry in the register of mutations, he must simultaneously post a complete copy of the entry in a conspicuous place in the chavdi (village office) and provide written intimation to all persons appearing from the record of rights or register of mutations to be interested in the mutation, including any other person whom he has reason to believe to be interested in the change. This public notice requirement serves as a fundamental safeguard against fraudulent or unauthorized mutations, ensuring that all parties with potential interests in the property receive actual notice of proposed changes.

The notice procedure under Section 135D has been modernized through the 2021 and 2022 amendments to the Gujarat Land Revenue Rules. These amendments introduced provisions for electronic service of notices alongside traditional manual service. When notices are served electronically, the rules require that email addresses of all interested persons must be provided in the application form, and a PDF copy of the Section 135D notice must be sent electronically while notices are also served manually. This dual-mode notification system ensures that no interested party can claim ignorance of the proposed mutation due to technological barriers.

The objection mechanism established under Section 135D(3) provides crucial protection for property rights. The provision mandates that should any objection to any entry made in the register of mutations be made in writing to the village accountant, it becomes the duty of the village accountant to enter the particulars of the objection in a register of disputed cases and to give written acknowledgment of receipt of such objection to the person making it. The time period for raising objections has been standardized at thirty days from the date of service of the last notice to persons having interest as mentioned in Section 135D(2). For specific types of mutations, particularly entry of orders by revenue officers or authorities, online encumbrance creation by banks, and removal of such encumbrances, a shorter period of ten days from the date of issuance of notice has been prescribed for finalizing the mutation if no objections are received.

Section 135D(4) addresses the resolution of objections entered in the register of disputed cases. The provision specifies that orders disposing of these objections shall be recorded in the register of mutations by such officers and in such manner as may be prescribed by rules made by the State Government. In practice, this means that the Mamlatdar exercises quasi-judicial powers to hear objections, examine evidence, and pass reasoned orders either accepting or rejecting the objections. These orders are subject to appeal before higher revenue authorities, creating a hierarchical system of dispute resolution.

The certification requirement under Section 135D(6) adds another layer of verification to the mutation process. Entries in the register of mutations must be tested and, if found correct or after correction as the case may be, certified by a revenue officer of rank not lower than that of a Mamlatdar’s first Karkun. This certification process serves as quality control, ensuring that mutations have been properly verified and that all procedural requirements have been satisfied before the entry becomes final.

The Detailed Process of Mutation

The mutation process in Gujarat follows a structured sequence of steps, each designed to ensure accuracy, transparency, and fairness. The process begins when a change in ownership or possession of land occurs through any legally recognized means such as sale, gift, inheritance, court decree, or government order. The person seeking mutation, typically the new owner or their legal representative, must file an application with the Talati of the village where the land is situated. This application must be accompanied by relevant documents establishing the basis for the transfer, such as a registered sale deed, succession certificate, will, court order, or other legally valid instruments.

Upon receiving the application, the Talati initiates a verification process to establish the authenticity of the documents and the legality of the transaction. This verification includes examining whether the transferor had legitimate title to the property, whether all co-owners have consented to the transfer where required, whether appropriate stamp duty has been paid, whether the property is subject to any prohibitions on transfer, and whether there are any existing disputes or encumbrances affecting the property. The Talati may also conduct a physical inspection of the land if deemed necessary to verify boundaries or resolve questions about the property’s identity.

After completing the initial verification, the Talati makes a provisional entry in Village Form No. 6. This entry is not immediately final but serves as a proposal for mutation. The Talati then triggers the notice procedure mandated under Section 135D by posting a complete copy of the proposed entry in a conspicuous place at the village chavdi and serving written notices to all known interested parties. These interested parties typically include previous owners, co-sharers, adjoining landowners who might be affected by the change, persons holding mortgages or other encumbrances on the property, and any other individuals who might have legitimate interests in the property.

The notice period, standardized at thirty days for most mutations, provides an opportunity for any interested party to examine the proposed mutation and raise objections if they believe the mutation is incorrect or improper. If objections are received, the Talati must record them in the register of disputed cases and provide written acknowledgment to the objector. The matter then enters the dispute resolution phase, where the Mamlatdar exercises quasi-judicial functions to adjudicate the dispute. The Mamlatdar examines the evidence presented by both parties, hears their arguments, and may conduct further inquiries if necessary before passing a reasoned order either allowing or rejecting the mutation.

If no objections are received within the stipulated period, or if objections are received but decided in favor of the mutation applicant, the process moves to the approval stage. The Mamlatdar reviews the mutation entry to ensure that all procedural requirements have been satisfied and that the entry is legally sound. Upon satisfaction, the Mamlatdar approves the mutation. In certain cases involving specific types of properties or transactions, the Collector’s sanction may additionally be required before the mutation becomes final.

After all necessary approvals are obtained, the final mutation entry is made in Village Form No. 6 and certified by the appropriate revenue officer as required under Section 135D(6). This certified entry becomes part of the permanent record of rights and can be relied upon as evidence of ownership in legal proceedings, subject to the rebuttable presumption established under Section 135J of the Gujarat Land Revenue Code.

Types of Transactions Recorded in the Mutation Register

The mutation register documents a wide variety of transactions and changes affecting land ownership and rights. Understanding these different types of mutations is essential for anyone dealing with land matters in Gujarat. The most common type of mutation relates to voluntary transfers through sale, where land is sold from one party to another through a registered sale deed. These sales must comply with various legal requirements including payment of stamp duty, registration under the Registration Act, and in certain cases, obtaining permissions from competent authorities.

Inheritance-based mutations, known as Vaarsai in local terminology, form another significant category. When a landowner passes away, their legal heirs become entitled to the property through succession. Gujarat recognizes two primary types of inheritance mutations. Vaarsai refers to mutations carried out after the death of the original owner, transferring ownership to legal heirs based on succession laws. Hayati Ma Hakk Dakhal, on the other hand, allows for transfer of rights to heirs while the original landowner is still alive, essentially permitting owners to effect succession planning during their lifetime.

Gift transactions, where land is transferred without consideration through a registered gift deed, also require mutation entries. Courts orders form another important category, particularly in cases involving partition suits, specific performance of contracts to sell, declaration of title, and other judicial determinations affecting land rights. When courts pass decrees relating to land, the court typically sends intimation to the revenue authorities, which then triggers the mutation process.

Government orders and acquisitions represent a distinct category of mutations. When government acquires land for public purposes under land acquisition laws, or when government makes other orders affecting land rights such as allotment of government land or cancellation of previous grants, these changes must be recorded through mutation entries. Similarly, changes in land classification, such as conversion from agricultural to non-agricultural use or vice versa, also necessitate mutation entries.

Financial encumbrances and their releases constitute yet another category of mutation entries. When landowners create mortgages or other charges on their property as security for loans, these encumbrances must be recorded in the mutation register. Subsequently, when loans are repaid and encumbrances are released, these releases too must be mutated. The 2021 amendments to the Gujarat Land Revenue Rules specifically address online creation of encumbrances by banks, streamlining the process for financial institutions while maintaining safeguards through the Section 135D notice procedure.

Family arrangements including partition of joint family property among co-sharers, rectification of previous errors in land records, and corrections based on survey operations also require mutation entries. Each of these transaction types follows the same basic procedural framework established under Section 135D, though specific requirements may vary depending on the nature of the transaction and the documents required to support it.

The Critical Role of the Talati

In the traditional conception of land revenue administration in Gujarat, the Talati occupies a position of special significance. An old saying compares the Talati to Chitragupta, the divine bookkeeper in Hindu mythology who maintains records of human deeds. Just as Chitragupta is believed to keep an account of every action, good or bad, that humans perform during their lives, the Talati maintains a meticulous record of every transaction and change affecting land within their jurisdiction. This comparison, while folksy, captures an essential truth about the Talati’s role as the primary custodian of land records at the grassroots level.

The office of Talati, also known as the Village Accountant, is established under the Gujarat Land Revenue Code and related rules. The Talati performs multiple functions extending well beyond mutation entries. These include maintaining various village-level registers and records, conducting land surveys and measurements, assessing land revenue, collecting certain categories of government dues, serving notices on behalf of revenue authorities, assisting in the preparation of electoral rolls, participating in disaster management activities at the village level, and serving as the first point of contact between villagers and the revenue administration.

In the mutation process specifically, the Talati bears several critical responsibilities. They must receive and process mutation applications, verify the authenticity of documents submitted with applications, conduct physical inspections when necessary, make provisional entries in Village Form No. 6, issue notices under Section 135D to all interested parties, maintain the register of disputed cases when objections are received, provide written acknowledgments for objections filed, and forward cases with objections to the Mamlatdar for adjudication.

The Talati’s position requires both technical knowledge of land records and revenue procedures, as well as judgment in identifying interested parties who should receive notice of proposed mutations. The accuracy of land records depends heavily on the diligence and integrity with which Talatis perform their duties. Recognition of this importance has led to various training programs and modernization initiatives aimed at enhancing the capacity of Talatis and reducing opportunities for corruption or negligence.

The digitization of land records through initiatives like E-Dhara and AnyRoR has significantly transformed the Talati’s working methods. Many functions that were previously manual are now performed through computerized systems, reducing the scope for manipulation of records and creating audit trails that enhance accountability. However, the Talati remains central to the system, as human judgment continues to be necessary for verification, identification of interested parties, and initial assessment of documents.

Hierarchical Structure and Appeals in Revenue Administration

The revenue administration system in Gujarat operates through a well-defined hierarchy, with each level possessing specific powers and responsibilities. Understanding this hierarchy is crucial because it determines how disputes are resolved and how decisions can be challenged. At the foundation of this hierarchy stands the Talati at the village level, responsible for maintaining day-to-day land records and initiating the mutation process. The Talati’s decisions and actions, however, are subject to supervision and review by higher authorities.

The Mamlatdar, appointed under Section 12 of the Gujarat Land Revenue Code, heads the revenue administration at the taluka level. Each taluka, representing an administrative subdivision of a district, typically comprises fifty or more villages. The Mamlatdar exercises supervisory authority over Talatis within the taluka and possesses quasi-judicial powers to resolve disputes arising from mutation entries and other land matters. When objections are filed against proposed mutations, the Mamlatdar conducts hearings, examines evidence, and passes binding orders disposing of the objections. The Mamlatdar also holds powers as an Executive Magistrate under Section 20 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, though these criminal jurisdiction powers are separate from revenue functions.

Above the Mamlatdar in the hierarchy stands the Collector, who heads the revenue administration of the entire district. The Collector, appointed under Sections 8 and 9 of the Gujarat Land Revenue Code, serves as the principal revenue authority and possesses extensive powers including supervision of all revenue officers within the district, hearing appeals against orders of Mamlatdars, exercising suo motu powers to review and revise orders of subordinate revenue authorities, sanctioning certain types of mutations that require higher approval, and coordinating between various departments on matters affecting land and revenue administration. The Collector represents the district in dealings with the state government and serves as the key link between grassroots administration and state-level policymaking.

The appellate structure within the revenue administration provides multiple tiers of review. When a Mamlatdar passes an order in a mutation dispute, the aggrieved party has the right to file an appeal before the Sub-Divisional Officer or the Collector, depending on the value and nature of the dispute. From the Collector’s orders, further appeals lie to the Special Secretary Revenue Department (SSRD), who exercises appellate and revisional jurisdiction over revenue matters across Gujarat. The SSRD’s orders generally represent the final word within the revenue administration hierarchy, though judicial review before the Gujarat High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution of India remains available for challenging orders on grounds of illegality, procedural irregularity, or violation of principles of natural justice.

This hierarchical structure ensures that errors can be corrected, disputes can be heard at multiple levels, and no single official exercises unchecked power over land matters. The system balances efficiency with fairness, allowing for quick resolution at lower levels while preserving opportunities for review when justice demands it.

The Digital Revolution: E-Dhara and AnyRoR

Gujarat has been at the forefront of digitizing land records in India, with initiatives dating back to the 1990s. The E-Dhara system, launched as part of the state’s broader e-governance efforts, represents one of the most significant modernization initiatives in land revenue administration. E-Dhara encompasses the digitization of all land records, online processing of mutations and other transactions, creation of digital archives of historical records, and integration with other government systems such as the registration department and banking sector.

The E-Dhara Kendras, established at the taluka level across Gujarat, serve as one-stop centers for land record services. Citizens can visit these centers to obtain certified copies of land records, submit applications for mutation, check the status of pending applications, file objections to proposed mutations, and access various other land-related services. The computerization has dramatically reduced the time required for various processes and minimized opportunities for corruption that previously plagued manual systems.

The AnyRoR (Any Records of Rights Anywhere) portal represents the public face of Gujarat’s digitized land record system.[6] Launched by the Revenue Department, Government of Gujarat, this online portal allows anyone with internet access to view land records from anywhere at any time. The portal provides access to various types of records including Village Form No. 7/12 which shows details of land ownership, cultivation status, and other vital information, Village Form No. 6 showing mutation history, Village Form No. 8A containing details of the landholder’s account, Section 135D notices for proposed mutations, and various other land-related records and documents.

The AnyRoR portal offers both free informational access and paid services for obtaining digitally signed Record of Rights that can be used for official purposes. The digitally signed documents carry legal validity equivalent to physical documents issued by revenue offices, having been authenticated through digital signature certificates issued under the Information Technology Act, 2000. This feature has eliminated the need for citizens to make repeated trips to revenue offices for obtaining certified land documents.

The digitization drive has yielded multiple benefits beyond mere convenience. Transparency has been enhanced as land records are now accessible to anyone, reducing information asymmetry between buyers and sellers in land transactions. Corruption opportunities have been minimized as automated systems leave audit trails and reduce scope for manipulation of records. Efficiency has improved dramatically, with many processes that previously took months now being completed in days or weeks. Accuracy has been enhanced through validation checks built into computerized systems and reduction of manual transcription errors. Accessibility has been transformed, with rural citizens able to access their land records without traveling to distant taluka or district headquarters.

The integration of the registration system with the revenue system represents another significant achievement. When a property is registered under the Registration Act, 1908, through the GARVI (Gujarat Automated Registration and Valuation of Immovables) portal, the system automatically triggers a mutation in the Record of Rights. This automation ensures that ownership records are updated without delay and reduces the burden on citizens who previously had to separately approach both the registration office and the revenue office for completing land transactions.

Legal Precedents and Judicial Interpretation

The interpretation and application of Section 135D and related provisions have been shaped significantly by judicial decisions, particularly from the Gujarat High Court. These precedents establish important principles that guide the administration of mutation procedures and protect the rights of property owners. Several landmark cases merit particular attention for the principles they establish and the impact they have had on mutation practice.

The mandatory nature of the notice requirement under Section 135D has been consistently emphasized by courts. Mutations conducted without proper notice to interested parties have been held to be legally invalid and susceptible to being set aside even years after their execution. The rationale behind this strict approach is that the notice procedure under Section 135D constitutes a fundamental safeguard of property rights, and failure to follow this procedure amounts to a breach of natural justice that renders subsequent mutation entries void from the beginning.

Courts have also clarified the nature of mutation entries and their evidentiary value. While Section 135J of the Gujarat Land Revenue Code creates a presumption of correctness for entries in the record of rights and register of mutations, courts have repeatedly held that this presumption is rebuttable and that mutation entries are not conclusive proof of ownership. A mutation entry creates a presumption in favor of the person in whose name the mutation stands, but this presumption can be rebutted by producing evidence showing that the mutation was obtained through fraud, misrepresentation, or without following proper procedures.

The burden of proof in disputes concerning mutations has been addressed in several cases. Generally, the party challenging a mutation entry bears the burden of proving that the entry is incorrect or was obtained improperly. However, if the challenger can show that basic procedural requirements like notice under Section 135D were not followed, the burden may shift to the party relying on the mutation to prove that proper procedures were followed. This allocation of burden ensures that parties cannot benefit from their own procedural violations while protecting those who have complied with legal requirements.

The scope of the Mamlatdar’s quasi-judicial powers under Section 135D has also been subject to judicial interpretation. Courts have held that the Mamlatdar exercises limited quasi-judicial functions in mutation disputes, primarily to determine whether a proposed mutation should be recorded based on the documents presented and whether all interested parties have been given an opportunity to object. However, the Mamlatdar cannot adjudicate questions of title in the full sense. If a dispute involves complex questions of title or requires interpretation of wills or other instruments, the Mamlatdar may note the dispute but cannot conclusively determine ownership. Such matters must be resolved by civil courts exercising regular jurisdiction over property disputes.

The relationship between registration of documents under the Registration Act and mutation under the Gujarat Land Revenue Code has been clarified through judicial pronouncements. Registration of a sale deed or other document creates a legal obligation on revenue authorities to record the mutation, provided proper notice is given and procedures are followed. However, registration alone does not automatically entitle a person to mutation if there are valid objections from interested parties. The revenue authorities must still follow the full Section 135D procedure and adjudicate any objections before recording the mutation.

Practical Implications and Best Practices

For anyone involved in land transactions in Gujarat, understanding the mutation process and following best practices can prevent future complications and protect property rights effectively. Before purchasing land, prospective buyers should invariably obtain and examine a copy of Village Form No. 6 for the property. This examination should verify the chain of title by checking whether the current seller’s name appears as the owner in the most recent certified mutation entry, ensuring that there are no gaps or unexplained breaks in the ownership chain, confirming that previous mutations were properly conducted with notices under Section 135D, and checking for any pending disputes recorded in the register of disputed cases.

Beyond examining Village Form No. 6, purchasers should also verify other related documents including Village Form No. 7/12 showing current ownership and land characteristics, certified copies of previous sale deeds and other transfer documents in the chain of title, no-objection certificates from revenue authorities confirming that there are no outstanding demands or disputes affecting the property, and encumbrance certificates from the registration office showing all registered transactions affecting the property.

After completing a purchase, the buyer must promptly initiate the mutation process. Delay in applying for mutation can create complications, as subsequent transactions by other parties might occur in the interim or questions might arise about the buyer’s intentions. The mutation application should be filed as soon as the sale deed is registered, accompanied by all necessary documents including the original registered sale deed, certified copy of the sale deed, proof of payment of stamp duty and registration fees, identity documents of both buyer and seller, proof of payment of any applicable revenue dues on the property, and any other documents specifically required by the revenue authorities.

During the mutation process, the applicant should actively monitor the progress by regularly checking the status of the application through the AnyRoR portal or by visiting the E-Dhara Kendra, ensuring that notices under Section 135D have been properly served to all interested parties, responding promptly to any queries or requirements from revenue authorities, and attending hearings if objections are filed. If objections are received, the applicant should engage legal representation or at least seek legal advice to understand the implications and formulate an appropriate response.

For those who discover that mutations have been wrongly recorded affecting their property, prompt action becomes essential. The first step should be filing a written objection with the Talati if the mutation is still in the objection period. If the mutation has already been certified, an application for cancellation or correction should be filed with the Mamlatdar, setting out the grounds on which the mutation is claimed to be improper and providing evidence supporting those grounds. If the Mamlatdar’s decision is unfavorable, appeals to higher revenue authorities including the Collector and Special Secretary Revenue Department should be pursued. As a last resort, a writ petition in the Gujarat High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution can be filed to challenge orders that are illegal or procedurally defective.

Conclusion

The mutation process and the role of Village Form No. 6 in Gujarat’s land revenue administration represent far more than bureaucratic procedures. They form the backbone of a system designed to maintain clear and reliable records of land ownership, prevent fraudulent transactions, provide transparency in land dealings, and protect the property rights of all citizens. The legal framework established by the Gujarat Land Revenue Code, particularly Section 135D, creates a balance between efficiency and fairness, allowing for timely recording of legitimate transactions while providing safeguards against improper changes.

Understanding this system becomes imperative for anyone involved in land transactions within Gujarat. The consequences of ignoring proper mutation procedures can be severe, including challenges to title, difficulty in obtaining financing, complications in further transfers, and protracted litigation. Conversely, careful attention to mutation procedures and thorough verification of land records before transactions can prevent most problems and ensure that property rights are secure.

The digitization initiatives undertaken by Gujarat, including E-Dhara and AnyRoR, have transformed access to land records and made the mutation process more transparent and efficient. These technological advances, combined with the solid legal framework established through decades of legislative development and judicial interpretation, position Gujarat’s land revenue administration among the most advanced in India. However, the ultimate success of any system depends on the vigilance of citizens in protecting their rights and their willingness to follow prescribed procedures. By understanding the mutation process, respecting legal requirements, and utilizing available tools like the AnyRoR portal, property owners and prospective buyers can navigate the land revenue system effectively and safeguard their interests.

References

[1] Gujarat Land Revenue Code, 1879. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/3215

[2] Revenue Department, Government of Gujarat. E-Dhara and Digitization of Land Records. Available at: https://revenuedepartment.gujarat.gov.in

[3] Government of Gujarat. Gujarat Land Revenue (Amendment) Rules, 2021. Available at: https://revenuedepartment.gujarat.gov.in/downloads/Notification_22122021.pdf

[4] AnyRoR Portal, Government of Gujarat. Available at: https://anyror.gujarat.gov.in

[5] Section 135D, Gujarat Land Revenue Code, 1879. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/2887119/

[6] Government of Gujarat. Gujarat Land Revenue (Amendment) Rules, 2022. Available at: https://revenuedepartment.gujarat.gov.in/downloads/rules_rd_31032022.pdf

Whatsapp

Whatsapp