Appeal to CIT(A): A Comprehensive Legal Guide

Introduction

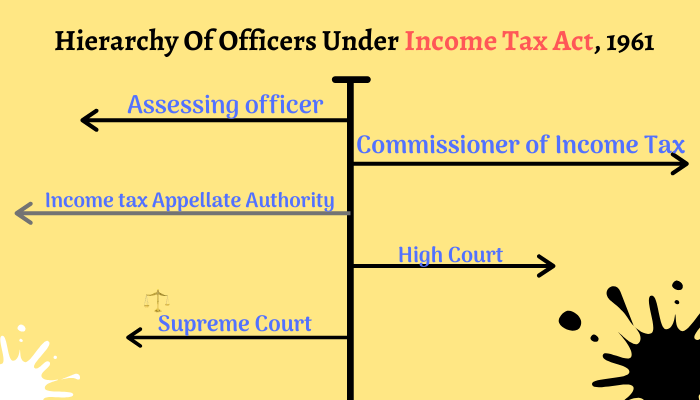

The appellate mechanism under the Income Tax Act, 1961 serves as a fundamental safeguard for taxpayers who find themselves aggrieved by orders passed by assessing officers. The right to appeal represents not merely a procedural formality but embodies the constitutional principle of natural justice, ensuring that taxpayers have access to remedial measures when they believe that assessment orders are erroneous in law or fact. Appeals to CIT(A), the Commissioner of Income Tax (Appeals), provide taxpayers with the first level of independent review, allowing them to seek redress before approaching higher judicial forums.

Understanding the Statutory Framework of Appeals

The statutory provisions governing appeals to the CIT(A) are primarily contained in Chapter XX of the Income Tax Act, 1961. The legislative framework encompasses several interconnected sections that collectively establish the comprehensive appellate mechanism. Section 246A of the Act serves as the cornerstone provision, delineating the specific categories of orders against which an assessee may prefer an appeal before the CIT(A). This section underwent significant amendments through the Finance (No.2) Act, 1998, which introduced a more comprehensive list of appealable orders, thereby expanding the scope of appellate remedies available to taxpayers [1].

The right to appeal is fundamentally statutory in nature, meaning it cannot be denied through administrative circulars or executive orders issued by the Central Board of Direct Taxes. The courts have consistently held that being a statutory right, it must be interpreted liberally to advance the cause of justice rather than to defeat it on technical grounds. This interpretive approach ensures that taxpayers are not deprived of their legitimate right to challenge erroneous orders merely due to procedural technicalities or minor delays that do not prejudice the revenue’s interests.

Parties to an Appeal and Their Rights

The Appeal process to Income tax commissioner involves two distinct parties, each with specific roles and responsibilities. The appellant, also referred to as the applicant, is the person who initiates the appeal by filing Form 35 before the CIT(A). In the context of first appeals under the Income Tax Act, only the assessee can assume the role of appellant. This includes individuals, Hindu Undivided Families, companies, firms, associations of persons, and any other entity that falls within the definition of “assessee” under Section 2(7) of the Act. The definition is deliberately comprehensive, encompassing not only persons liable to pay tax but also those in respect of whom assessment proceedings have been initiated, even if no tax liability ultimately crystallizes.

The respondent in an appeal before the CIT(A) is typically the assessing officer whose order is being challenged. The assessing officer is required to submit a remand report, defend the assessment order, and participate in the appellate proceedings. The dynamic between the appellant and respondent is governed by principles of natural justice, requiring that both parties receive adequate opportunity to present their case and respond to each other’s contentions. The CIT(A) acts as a quasi-judicial authority, examining the evidence and arguments presented by both sides before arriving at an independent conclusion on the merits of the appeal.

Appealable Orders Under Section 246A

Section 246A comprehensively enumerates the orders against which an assessee may file an appeal before the CIT(A). The provision covers a wide spectrum of orders, ensuring that taxpayers have appellate remedies across various stages and types of assessment proceedings. One of the primary categories includes orders where the taxpayer denies liability to be assessed under the Income Tax Act altogether. This encompasses situations where the fundamental question of taxability itself is in dispute, such as cases involving jurisdictional issues, status determination, or applicability of specific provisions.

Intimations issued under Section 143(1) or Section 143(1B) constitute another significant category of appealable orders. These intimations are issued when the Income Tax Department processes returns and makes adjustments to the income declared by the taxpayer. Prior to amendments in the law, such intimations were not appealable, causing considerable hardship to taxpayers who had no remedy against erroneous adjustments made during summary processing. The legislature recognized this anomaly and made these intimations appealable, thereby providing taxpayers with an effective remedy against prima facie incorrect adjustments [2].

Assessment and Reassessment Orders

Regular assessment orders passed under Section 143(3) following scrutiny proceedings constitute the most common category of appealable orders. These orders are passed after the assessing officer conducts detailed examination of the taxpayer’s accounts, evidence, and submissions. Similarly, best judgment assessment orders under Section 144, which are passed in cases of non-cooperation or failure to maintain proper books of account, are also appealable. The provision ensures that even in cases where the assessee has not cooperated fully during assessment proceedings, the right to appeal remains protected.

Reassessment orders passed under Section 147 after reopening concluded assessments on the grounds that income has escaped assessment represent another crucial category. These proceedings often involve complex questions regarding the validity of reasons recorded for reopening and the existence of tangible material justifying the belief that income has escaped assessment. The right to appeal against such orders is particularly significant given the potential for arbitrary exercise of reopening powers by tax authorities.

Penalty Orders and Other Appealable Orders

The legislative framework provides for appeals against penalty orders imposed under various sections of the Income Tax Act. These include penalties for concealment of income under Section 271, failure to furnish returns under Section 271F, failure to deduct tax at source, and numerous other defaults. Penalty proceedings are quasi-criminal in nature, and the right to appeal ensures that taxpayers can challenge penalties imposed without adequate evidence or in violation of principles of natural justice.

Additionally, orders treating persons as assessees in default under Section 201 for failure to deduct or deposit tax at source are appealable. Rectification orders under Sections 154 and 155, orders determining tax refunds under Section 237, and orders passed under Section 163 treating a person as an agent of a non-resident also fall within the ambit of appealable orders. This comprehensive coverage ensures that taxpayers have appellate remedies across the entire spectrum of income tax proceedings.

Time Limit for Filing Appeals

Section 249(2) prescribes a strict time limit of thirty days for filing appeals before the CIT(A). The commencement point for calculating this period varies depending on the nature of the order being appealed. For appeals relating to assessment or penalty orders, the thirty-day period begins from the date of service of the notice of demand relating to such assessment or penalty. This provision recognizes that the notice of demand, which quantifies the tax liability and directs payment, serves as the trigger for the taxpayer to evaluate whether to accept the assessment or challenge it through appeal.

In cases where the appeal relates to other matters not involving assessment or penalty, such as rectification orders or rejection of applications, the time limit runs from the date on which the intimation of the order sought to be appealed is served on the assessee. The calculation of the thirty-day period must be done carefully, excluding the date of service of the order as mandated by Section 268 of the Act. This exclusion principle ensures that taxpayers receive the full benefit of the prescribed limitation period.

Condonation of Delay in Filing Appeals

Recognizing that taxpayers may face genuine difficulties in filing appeals within the prescribed time limit, Section 249(3) empowers the CIT(A) to admit appeals filed beyond thirty days if sufficient cause is shown for the delay. The power to condone delay is discretionary and must be exercised judiciously after examining the reasons for delay and determining whether they constitute sufficient cause. The Supreme Court in the landmark judgment of Collector, Land Acquisition v. Mst. Katiji has laid down comprehensive principles governing condonation of delay, emphasizing that the approach should be liberal rather than pedantic [3].

The Court observed that ordinarily, litigants do not stand to benefit by lodging appeals late, and refusing to condone delay can result in meritorious matters being thrown out at the threshold, thereby defeating the cause of justice. The expression “every day’s delay must be explained” should not be interpreted literally in a pedantic manner. What matters is whether the delay is due to deliberate negligence or mala fide conduct, or whether it results from circumstances beyond the appellant’s reasonable control. When substantial justice and technical considerations are pitted against each other, the cause of substantial justice deserves preference, as the other side cannot claim a vested right in injustice being perpetuated due to non-deliberate delays.

Appeal Fees and Payment Procedures

Section 249(1) mandates payment of prescribed fees at the time of filing appeals before the CIT(A). The quantum of fees is determined based on the total income or loss computed by the assessing officer in the order being appealed. Where the assessed income does not exceed one lakh rupees, the prescribed fee is two hundred fifty rupees. For assessed income exceeding one lakh rupees but not exceeding two lakh rupees, the fee increases to five hundred rupees. In cases where the assessed income exceeds two lakh rupees, the fee payable is one thousand rupees. For appeals relating to matters other than income determination, such as procedural issues, a flat fee of two hundred fifty rupees is prescribed [4].

The fee structure is deliberately kept reasonable to ensure that the right to appeal is not denied to taxpayers due to financial constraints. The payment must be made through the prescribed electronic payment system, and proof of payment in the form of a challan must accompany the appeal. The challan details, including the Bank Scroll Reference (BSR) code, date of payment, serial number, and amount of fee, must be accurately mentioned in Form 35 to establish that the mandatory fee requirement has been fulfilled.

Procedure for Filing Appeals Through Form 35

The procedural requirements for filing appeals are governed by Section 249 read with Rule 45 of the Income Tax Rules, 1962. Form 35 serves as the prescribed format for presenting appeals before the CIT(A). With the advent of electronic filing, the Income Tax Department has mandated online submission of Form 35 through the e-filing portal for all taxpayers for whom electronic filing of returns is compulsory. This digitization initiative has significantly streamlined the appeal filing process, reducing physical paperwork and enabling faster processing of appeals.

The appeal must contain essential elements including a clear statement of facts presenting the chronological sequence of events leading to the assessment, the grounds of appeal articulating specific legal and factual objections to the assessment order, and verification by the authorized signatory. The statement of facts should be concise yet comprehensive, providing the CIT(A) with a complete understanding of the background and context of the dispute. The grounds of appeal constitute the heart of the appeal, delineating the specific errors alleged in the assessment order and the relief sought by the appellant.

Documents Required for Filing Appeals

Several documents must accompany Form 35 to constitute a complete and valid appeal. A certified copy of the order being appealed against must be attached, enabling the CIT(A) to examine the impugned order in detail. The original notice of demand must also be submitted, as it formally communicates the tax liability determined in the assessment. The challan evidencing payment of the prescribed appeal fee is mandatory, and failure to attach it renders the appeal defective. In cases where the appeal is filed belatedly, an application for condonation of delay explaining the reasons for delayed filing must be submitted.

Additionally, taxpayers may attach supporting documents, evidence, and judicial precedents that substantiate their contentions. While the CIT(A) has powers under Rule 46A to admit additional evidence not produced during assessment proceedings, it is prudent for appellants to compile and submit all relevant documents along with the appeal itself. This ensures that the CIT(A) has complete information to adjudicate the appeal effectively without unnecessary delays in calling for additional evidence.

Pre-deposit Requirements and Exemptions

Section 249(4) contains a crucial provision requiring appellants to pay certain amounts before filing appeals. Where the appellant has filed a return of income, the amount of tax determined as per such return must be paid before presenting the appeal. In cases where no return has been filed, an amount equal to the advance tax payable by the assessee must be deposited. This pre-deposit requirement aims to prevent frivolous appeals being filed merely to delay revenue collection, while simultaneously protecting genuine appellants by limiting the pre-deposit to admitted tax liability rather than the disputed demand.

Recognizing that rigid application of the pre-deposit requirement may cause undue hardship in certain situations, the provision empowers the CIT(A) to exempt appellants from making the pre-deposit if good and sufficient reasons are established. Courts have held that this exemption power must be exercised fairly, considering the appellant’s financial circumstances, prima facie merits of the case, and likelihood of success in the appeal. The appellant must make a specific application explaining why the pre-deposit requirement should be waived, supported by relevant evidence and documents [5].

Powers of the Commissioner of Income Tax (Appeals)

The CIT(A) exercises extensive powers while hearing and disposing of appeals. Section 250 confers wide-ranging authority including the power to confirm, reduce, enhance, or annul the assessment. The enhancement power is particularly significant, as it enables the CIT(A) to increase the assessed income even without any appeal by the revenue department. However, this power must be exercised cautiously and only after affording the assessee adequate opportunity to be heard on the proposed enhancement. The principle of natural justice mandates that an assessee should not be taken by surprise with an enhancement without prior notice and opportunity to present submissions.

The CIT(A) also possesses the power to set aside the assessment and direct fresh assessment by the assessing officer when necessary. This power is typically exercised when the CIT(A) finds that the assessing officer has not conducted adequate enquiries or has failed to consider relevant evidence. The power to set aside ensures that the appellate authority can remedy procedural irregularities and ensure that assessments are conducted in accordance with law and principles of natural justice.

Admission of Additional Evidence

Rule 46A of the Income Tax Rules governs the admission of additional evidence during appellate proceedings. The provision recognizes four specific circumstances under which the CIT(A) may admit evidence that was not produced during assessment proceedings. First, if the assessing officer has refused to admit evidence that ought to have been admitted. Second, if the appellant was prevented by sufficient cause from producing the evidence despite having requested the opportunity. Third, if the assessing officer passed the order without giving the appellant reasonable opportunity to adduce relevant evidence. Fourth, if the CIT(A) requires any document to be produced or witness to be examined to enable it to pass orders on the appeal.

Before admitting additional evidence, the CIT(A) must record reasons for such admission and provide the assessing officer an opportunity to examine the evidence and submit a remand report. This procedural safeguard ensures that the revenue’s interests are protected and prevents appellants from introducing entirely new evidence at the appellate stage without justification. The provision strikes a balance between ensuring thorough examination of all relevant evidence and preventing misuse of the appellate process.

Faceless Appeals Scheme and Procedural Reforms

The Central Board of Direct Taxes introduced the Faceless Appeal Scheme in 2020, fundamentally transforming the appellate process by eliminating physical interface between taxpayers and tax authorities. Under this scheme, all communications between the appellant, assessing officer, and CIT(A) occur electronically through the National Faceless Appeal Centre. The scheme aims to enhance transparency, eliminate corruption, and ensure uniform application of law across the country by eliminating regional variations in interpretation and application of provisions [6].

The faceless appeals process begins when the National Faceless Appeal Centre receives Form 35 through the e-filing portal. The Centre then assigns the appeal to an appropriate appeal unit based on automated allocation mechanisms. The entire appellate proceedings, including issuance of notices, submission of responses, and conduct of hearings through video conferencing, are conducted electronically. The final appellate order is also issued electronically through the Centre, ensuring complete auditability and transparency in the decision-making process.

Disposal of Appeals and Time Limits

The Income Tax Act envisions speedy disposal of appeals to reduce litigation pendency and provide timely relief to taxpayers. Section 250 contemplates that the CIT(A) should dispose of appeals within one year from the end of the financial year in which the appeal is filed, wherever possible. While this is a directory provision rather than mandatory, it reflects the legislative intent that appeals should not remain pending indefinitely. Tax authorities are expected to prioritize disposal of appeals and adopt efficient case management practices to achieve timely resolution.

The CIT(A) is required to pass a detailed order addressing each ground of appeal raised by the appellant. The order must contain findings of fact, application of law to those facts, and clear conclusions on each issue. Adequate reasoning must be provided for accepting or rejecting each ground, as appellate orders are subject to further appeal before the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal. A well-reasoned order not only provides clarity to the parties but also facilitates expeditious disposal of subsequent appeals by higher forums.

Judicial Interpretation and Landmark Pronouncements

The appellate provisions have been subject to extensive judicial interpretation over the decades, resulting in a rich body of precedents that guide their application. Courts have consistently emphasized that the right to appeal, being statutory in nature, must be interpreted liberally to advance the cause of justice. Technical objections regarding compliance with procedural requirements should not be permitted to defeat substantive rights unless the defect is fundamental and incurable.

The Supreme Court has held in various judgments that appellate authorities should focus on deciding appeals on merits rather than dismissing them on technical grounds. The Court has emphasized that when two views are possible on a question of law, and the assessing officer has adopted a view favorable to the assessee, the appellate authority should not interfere merely because it prefers a different interpretation. This principle promotes consistency in tax administration and prevents harassment of taxpayers through repeated challenges to settled positions [7].

Recent Developments and Future Directions

Recent years have witnessed significant reforms in the appellate framework aimed at improving efficiency and taxpayer convenience. The introduction of the Joint Commissioner (Appeals) as an additional appellate authority for certain categories of cases has helped reduce the burden on CIT(A) and ensure faster disposal of appeals involving smaller tax effects. The Finance Act 2023 designated the Joint Commissioner (Appeals) to handle appeals in specified categories of cases, particularly those involving lower tax amounts or less complex legal issues [8].

The ongoing digitization of tax administration has transformed the appeals process, making it more accessible and transparent. Taxpayers can now file appeals, track their status, and receive orders electronically without physical visits to tax offices. This technological transformation has been particularly beneficial during the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring continuity of appellate proceedings despite physical restrictions. The success of faceless appeals has led to plans for further enhancement of the digital infrastructure supporting appellate processes.

Practical Considerations for Appellants

Taxpayers contemplating filing appeals must carefully evaluate several practical considerations. First, the grounds of appeal must be drafted precisely, identifying specific errors in the assessment order and providing legal and factual arguments supporting each ground. Vague or omnibus grounds that merely express dissatisfaction with the assessment without identifying specific errors are unlikely to succeed. Each ground should be self-contained, clearly stating the grievance, the applicable law, and the relief sought.

Second, appellants should maintain realistic expectations about the time required for disposal of appeals. While the law envisions disposal within one year, practical experience shows that complex cases may take longer, particularly when additional evidence needs to be examined or remand reports are required from assessing officers. Appellants should maintain regular follow-up with the CIT(A)’s office and respond promptly to any notices or queries issued during the appellate proceedings.

Third, professional representation by qualified chartered accountants or tax advocates can significantly enhance the prospects of success in appeals. These professionals possess expertise in tax law, familiarity with judicial precedents, and experience in presenting cases effectively before appellate authorities. While the law permits appellants to appear personally, complex technical issues and intricate legal questions often benefit from professional expertise and advocacy [9].

Conclusion

The appellate mechanism under the Income Tax Act serves as a vital safeguard for taxpayer rights, providing an institutional framework for correcting errors and ensuring that tax assessments are made in accordance with law and principles of natural justice. The comprehensive statutory framework governing appeals to the CIT(A) balances the interests of revenue collection with the protection of taxpayer rights, ensuring that genuine grievances receive fair and impartial adjudication. The first level of appeal before the CIT(A) plays a crucial role in filtering cases, resolving disputes expeditiously, and reducing the burden on higher appellate forums.

As tax administration continues to evolve with technological advancement and procedural reforms, the appellate process has become more accessible, transparent, and efficient. The faceless appeals scheme represents a paradigm shift in how appellate proceedings are conducted, eliminating human interface and promoting uniformity in decision-making. However, the fundamental principles underlying the appellate process remain unchanged: ensuring that every taxpayer receives a fair hearing, decisions are based on merits rather than technicalities, and substantial justice prevails over procedural formalities.

Taxpayers must remain informed about their appellate rights and exercise them judiciously when faced with erroneous assessment orders. The success of the appellate mechanism depends not only on the statutory framework and institutional arrangements but also on the active participation of taxpayers in presenting their cases effectively and engaging constructively with the appellate process. By understanding the procedural requirements, time limits, and substantive provisions governing appeals, taxpayers can navigate the appellate process successfully and secure appropriate relief against unjust tax demands.

References

[1] Taxmann. (2022). “Which Orders are Appealable Before the CIT Appeals?” Taxmann Blog. Available at: https://www.taxmann.com/post/blog/appealable-orders-before-the-commissioner-appeals/

[2] Income Tax Department. (n.d.). “Form 35 FAQ.” Official Portal of Income Tax Department. Available at: https://www.incometax.gov.in/iec/foportal/help/statutory-forms/popular-form/form35-faq

[3] Supreme Court of India. (1987). Collector, Land Acquisition, Anantnag v. Mst. Katiji & Ors., (1987) 2 SCC 107, AIR 1987 SC 1353. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1117226/

[4] KanoonGPT. (n.d.). “Section 249: Form of Appeal and Limitation – The Income Tax Act 1961.” Available at: https://kanoongpt.in/bare-acts/the-income-tax-act-1961/section-249-70c0a6e591abc0d7

[5] TaxGuru. (2024). “All About Filing an Appeal Before CIT(A).” TaxGuru. Available at: https://taxguru.in/income-tax/filing-appeal-cita.html

[6] Taxmann. (2024). “All About Appeal Before CIT/JCIT (Appeals) – Time Limit, Procedure, Fee.” Taxmann Blog. Available at: https://www.taxmann.com/post/blog/all-about-appeal-before-cit-appeals/

[7] Supreme Court of India. (2007). Max India Ltd. v. Commissioner of Income Tax, (2007) 295 ITR 282 (SC). Available at: https://www.lawfinderlive.com/archivesc/197391.htm

[8] Indian Kanoon. (n.d.). “Section 249(2) in The Income Tax Act, 1961.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1905543/

[9] IndiaFilings. (2024). “Appeal to Commissioner of Income Tax.” IndiaFilings. Available at: https://www.indiafilings.com/learn/appeal-to-commissioner-of-income-tax/

Authorized and Published by

Prapti Bhatt

Whatsapp

Whatsapp