Constitutional Morality Vs Popular Morality: A Judicial Discourse on Rights and Freedoms in India

Introduction

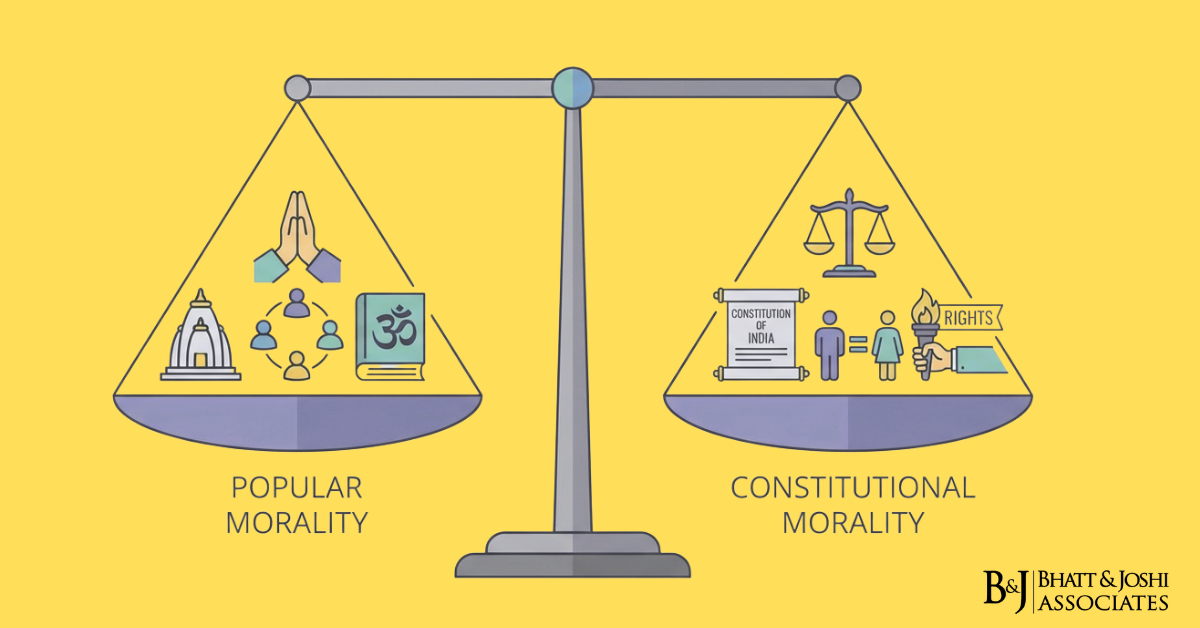

The tension between constitutional morality and popular morality represents one of the most significant debates in contemporary Indian jurisprudence. This conflict arises when societal norms, customs, and traditions clash with the fundamental principles enshrined in the Constitution of India. The doctrine of constitutional morality has emerged as a powerful judicial tool to protect individual rights and freedoms against majoritarian sentiments that may perpetuate discrimination or violate constitutional values. Understanding this concept requires examining its philosophical foundations, legislative frameworks, and the landmark judicial pronouncements that have shaped its application in modern India.

Conceptual Framework of Constitutional Morality

Historical Origins and Development

The term “constitutional morality” finds its intellectual roots in the works of George Grote, a nineteenth-century historian who analyzed Athenian democracy. Grote described constitutional morality as a supreme reverence for the forms of the Constitution, extending beyond mere obedience to encompass a deeper respect for constitutional principles and democratic governance. This concept was later embraced by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar during the Constituent Assembly debates on November 4, 1948, when he emphasized that constitutional morality meant effective coordination between conflicting interests of different people and administrative cooperation to resolve them amicably without confrontation.[1]

Dr. Ambedkar’s vision of constitutional morality was intrinsically linked to his fight against social inequalities, particularly the caste system. He viewed it as a solution to existing inequalities in society, representing respect among parties in a republic for constitutional democracy as the preferred form of governance. Unlike Grote’s emphasis on procedural adherence, Ambedkar’s interpretation was more substantive, focusing on the Constitution’s role in achieving social transformation and protecting vulnerable minorities from majoritarian tyranny.

Constitutional Provisions and Legal Framework

While the term “constitutional morality” does not appear explicitly in the Constitution of India, its essence permeates the document’s core provisions. The fundamental framework is built upon the Preamble, which enshrines justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity as cardinal constitutional values. These principles find concrete expression in Part III of the Constitution, which guarantees fundamental rights to all persons within Indian territory.

Article 14 guarantees equality before law and equal protection of laws, prohibiting arbitrary state action and ensuring that legislative classifications must be based on intelligible differentia with a rational nexus to the object sought to be achieved. Article 15 specifically prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth, though it permits affirmative action for socially and educationally backward classes. Article 19 protects fundamental freedoms including freedom of speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, and profession, subject to reasonable restrictions in the interests of sovereignty, integrity, public order, decency, or morality. Article 21, perhaps the most expansive fundamental right, protects life and personal liberty, which judicial interpretation has expanded to include dignity, privacy, and various other rights essential for meaningful human existence.[2]

Articles 25 and 26 protect freedom of religion, guaranteeing individuals the right to profess, practice, and propagate religion, while also conferring on religious denominations the right to manage their own affairs in matters of religion. However, these rights are subject to public order, morality, and health. The critical question that has repeatedly come before courts is whether the “morality” mentioned in these provisions refers to popular morality or constitutional morality.

Landmark Judicial Pronouncements

Naz Foundation v. Government of NCT of Delhi (2009)

The Delhi High Court’s decision in Naz Foundation v. Government of NCT of Delhi marked a watershed moment in Indian jurisprudence by distinguishing between constitutional morality and popular morality.[3] The case challenged Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalized consensual sexual acts between adults of the same sex as “carnal intercourse against the order of nature.” The Naz Foundation, an organization working on HIV/AIDS prevention, argued that this colonial-era provision violated fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 15, 19, and 21 of the Constitution.

The High Court held that Section 377, insofar as it criminalized consensual sexual acts between adults in private, was unconstitutional. The judgment emphasized that constitutional morality, not popular morality, must guide judicial interpretation of fundamental rights. The Court observed that public animus or disgust toward a particular social group cannot constitute a valid ground for classification under Article 14. The decision recognized that sexual orientation is analogous to the protected ground of “sex” under Article 15, and discrimination on this basis violates constitutional guarantees of equality and non-discrimination.

Significantly, the Court held that the right to privacy under Article 21 includes decisional autonomy regarding intimate personal choices. The judgment stated that if individuals act consensually without harming others in expressing their sexuality, state invasion of that sphere breaches constitutional privacy protections. This landmark decision was, however, subsequently overturned by the Supreme Court in 2013, only to be ultimately vindicated in 2018.

Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018)

The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India represents the most authoritative pronouncement on constitutional morality in Indian legal history.[4] A five-judge Constitution Bench comprising Chief Justice Dipak Misra, Justice R.F. Nariman, Justice A.M. Khanwilkar, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, and Justice Indu Malhotra delivered four concurring opinions, each providing unique perspectives on constitutional morality while arriving at the same conclusion.

The Court partially struck down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, decriminalizing consensual sexual relations between adults of the same sex while maintaining the provision’s applicability to non-consensual acts, acts involving minors, and bestiality. The judgment held that Section 377 violated Articles 14, 15, 19, and 21 of the Constitution by arbitrarily criminalizing individuals based on their sexual orientation, thereby treating them as “less than humans” and perpetuating prejudice and discrimination.

Justice Chandrachud’s opinion emphasized that constitutional morality reflects the ideal of justice as an overriding factor against social acceptance. He observed that constitutional morality requires conscious efforts to cultivate norms of fidelity to constitutional values such as equality, liberty, and fraternity. The judgment clarified that Victorian morality, which formed the basis of Section 377, had long become obsolete and could not justify continuing criminalization of consensual adult relationships. Justice Nariman’s opinion imposed an obligation on the Union of India to publicize the judgment widely to eliminate stigma faced by the LGBTQ community.

Joseph Shine v. Union of India (2018)

Shortly after the Navtej Singh Johar decision, the Supreme Court again invoked constitutional morality in Joseph Shine v. Union of India, striking down Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code which criminalized adultery.[5] Section 497 made adultery a criminal offense only for men who engaged in sexual intercourse with another man’s wife without the husband’s consent, while exempting women from prosecution even as abettors. Section 198(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure further provided that only the husband could file a complaint in adultery cases.

The five-judge Constitution Bench unanimously held that Section 497 violated Articles 14, 15, and 21 by treating women as property of their husbands and denying them sexual autonomy and agency. Chief Justice Misra’s opinion emphasized that husbands are not masters of their wives, and the provision was based on outdated patriarchal notions inconsistent with constitutional values of gender equality and dignity. The Court observed that while adultery might constitute grounds for civil remedies like divorce, criminalizing it amounted to state intrusion into the extreme privacy sphere of matrimonial relationships.

Justice Chandrachud’s concurring opinion drew parallels with Navtej Singh Johar, highlighting that sexual autonomy constitutes an essential aspect of individual liberty protected under Article 21. The judgment represented another victory for constitutional morality over traditional social morality that had long perpetuated gender stereotypes and women’s subordination in marriage.

Indian Young Lawyers Association v. State of Kerala (2018)

The Sabarimala Temple case presented the Supreme Court with perhaps its most controversial application of constitutional morality.[6] The case challenged the prohibition on entry of women aged 10 to 50 years into the Sabarimala Temple in Kerala, which was justified on the ground that Lord Ayyappa, the presiding deity, was a celibate and the presence of menstruating women would violate this celibacy. Rule 3(b) of the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Rules, 1965, provided legal sanction to this exclusionary practice based on custom.

By a 4:1 majority, the Supreme Court held that the exclusion violated Articles 14, 15, 17, 21, and 25 of the Constitution. The majority opinions, authored by Chief Justice Misra, Justice Nariman, Justice Chandrachud, and Justice Khanwilkar, held that constitutional morality must prevail over customs that discriminate against women based on biological characteristics. The Court ruled that devotees of Lord Ayyappa did not constitute a separate religious denomination under Article 26, and even if they did, the exclusionary practice was not an essential religious practice deserving constitutional protection.

The judgment emphasized that physiological features like menstruation cannot determine rights of worship, and such exclusion perpetuates notions of women being “impure” during menstruation, which contradicts constitutional values of equality and dignity. Justice Chandrachud’s opinion articulated that the term “morality” in Articles 25 and 26 must mean constitutional morality, not popular morality based on social acceptance or traditional customs. However, Justice Indu Malhotra dissented, arguing that courts should not interfere with matters of religion and faith in a secular polity, and that the issue was essentially one for the religious community to decide.

The Sabarimala judgment sparked unprecedented public protests and led to over fifty review petitions being filed. In 2019, a five-judge bench by a 3:2 majority referred the matter to a larger nine-judge bench to consider broader questions about the interplay between constitutional morality and religious freedom. This reference remains pending, highlighting the ongoing tension between judicial interpretation of constitutional values and religious practices rooted in tradition.

Regulatory Framework and Legislative Response

Constitutional Amendments and Statutory Provisions

The application of constitutional morality has not required formal constitutional amendments, as courts have derived this principle from existing constitutional provisions. However, various statutes reflect the Parliament’s recognition of constitutional values over traditional social norms. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, recognizes women’s right to live free from violence regardless of marital status. The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, implements constitutional mandates of gender equality in employment. The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006, criminalizes a practice that was once widely accepted as social custom but violates constitutional guarantees of children’s rights.

Judicial Review and Constitutional Supremacy

Article 13 of the Constitution declares that any law inconsistent with fundamental rights shall be void to the extent of inconsistency. This provision empowers courts to strike down legislation and invalidate customs that violate constitutional morality. The doctrine of constitutional morality strengthens judicial review by providing courts with a principled framework to evaluate whether laws and practices conform to constitutional values beyond mere textual compliance.

The basic structure doctrine, established in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), holds that certain fundamental features of the Constitution cannot be altered even through constitutional amendments. In Government of NCT of Delhi v. Union of India (2018), the Supreme Court equated constitutional morality to a “second basic structure doctrine,” emphasizing that adherence to constitutional principles is essential for preserving democratic governance and institutional integrity.[7]

Challenges and Criticisms

Democratic Legitimacy and Judicial Overreach

Critics argue that the doctrine of constitutional morality enables judicial activism that undermines democratic principles by allowing unelected judges to override popularly enacted laws and long-standing social practices. Former Attorney General K.K. Venugopal described constitutional morality as a “dangerous weapon” that could transform the Supreme Court into a “third parliamentary chamber.” This criticism reflects concerns about separation of powers and the proper boundaries between legislative policymaking and judicial interpretation.

Definitional Ambiguity and Subjective Interpretation

The absence of a precise definition of constitutional morality in the Constitution or statute leaves its scope open to individual judicial interpretation. This ambiguity creates unpredictability in legal outcomes and raises concerns about judicial subjectivity replacing legislative deliberation. Different judges may have varying conceptions of what constitutional morality requires, potentially leading to inconsistent applications of the doctrine.

Conflict with Religious Freedom and Cultural Diversity

India’s constitutional framework protects both individual rights and collective religious freedoms, creating inherent tensions when these values conflict. Critics of the Sabarimala judgment argue that imposing a uniform standard of constitutional morality on diverse religious traditions fails to respect the autonomy of religious communities guaranteed under Article 26. They contend that courts should adopt a more nuanced approach that balances constitutional values with religious and cultural pluralism.

Conclusion

The doctrine of constitutional morality has emerged as a transformative principle in Indian constitutional law, providing courts with a framework to protect fundamental rights against majoritarian sentiments and discriminatory traditions. Through landmark judgments in cases involving sexual orientation, gender equality, and religious practices, the Supreme Court has established that constitutional values must prevail over popular morality when the two conflict. While this doctrine faces criticism regarding democratic legitimacy and judicial overreach, it remains essential for safeguarding individual dignity and liberty in a diverse democracy. The ongoing debate about constitutional morality’s proper scope and limits will continue to shape Indian jurisprudence as courts navigate the complex relationship between constitutional values, legislative authority, and social transformation. As the larger bench consideration of the Sabarimala case demonstrates, finding the appropriate balance between constitutional principles and religious freedom remains one of the most challenging tasks facing Indian constitutional law today.

References

[1] Constitutional Morality, Drishti IAS. Available at: https://www.drishtiias.com/to-the-points/Paper2/constitutional-morality

[2] Fundamental Rights in India, Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_rights_in_India

[3] Naz Foundation v. Government of NCT of Delhi, WP(C) 7455/2001, Delhi High Court (2009). Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/100472805/

[4] Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India, AIR 2018 SC 4321. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/168671544/

[5] Joseph Shine v. Union of India, AIR 2019 SC 1601. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/42184625/

[6] Indian Young Lawyers Association v. State of Kerala, (2019) 11 SCC 1. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/163639357/

[7] Constitutional Morality in India, iPleaders. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/constitutional-morality-in-india/

Whatsapp

Whatsapp