The Indian Banking System: Regulatory Framework, Legal Foundations and Judicial Interpretations

Introduction to the Indian Banking System

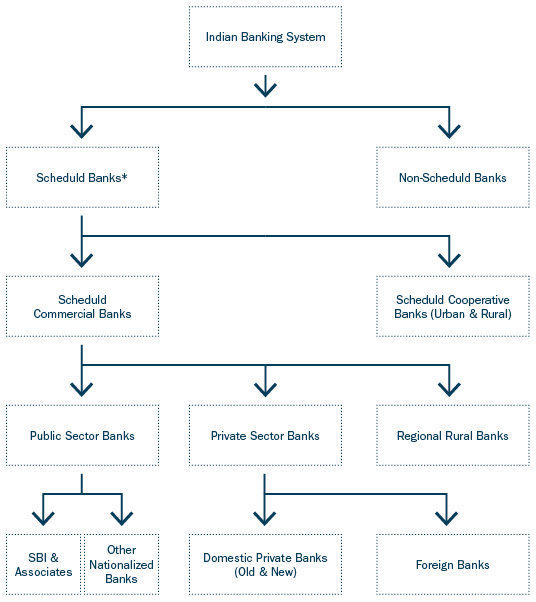

The Indian banking system stands as one of the most sophisticated financial infrastructures in the developing world, characterized by its multi-layered regulatory framework and judicial oversight mechanisms. This banking architecture has evolved significantly since independence, transitioning from a fragmented colonial-era system to a robust, regulated framework that balances financial stability with economic growth imperatives. The system operates under the primary supervision of the Reserve Bank of India, which functions as the central banking authority and regulatory overseer of all banking operations within the country. Understanding the legal and regulatory foundations of this system requires examining the statutory framework, administrative regulations, and judicial interpretations that collectively shape banking operations in India.

The Indian banking system encompasses various categories of institutions, including commercial banks, cooperative banks, regional rural banks, and non-banking financial companies. Each category operates under specific regulatory requirements designed to ensure financial stability, protect depositor interests, and facilitate credit flow to productive sectors of the economy. The regulatory architecture has been carefully constructed through multiple legislative enactments, each addressing specific aspects of banking operations and financial intermediation.

Legislative Structure of the Indian Banking System

The Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934

The foundational legislation establishing India’s central banking authority and regulating the Indian banking system is the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 [1]. This Act came into force on March 6, 1934, creating a statutory body responsible for regulating currency issuance, maintaining monetary stability, and operating the country’s credit system. The preamble to the Act articulates its primary objective: “to constitute a Reserve Bank for India to regulate the issue of Bank notes and the keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary stability in India and generally to operate the currency and credit system of the country to its advantage.”

The Act underwent significant amendments in subsequent years, particularly with the insertion of provisions establishing a modern monetary policy framework. The amended preamble now recognizes that “it is essential to have a modern monetary policy framework to meet the challenge of an increasingly complex economy” and that “the primary objective of the monetary policy is to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth.” This legislative recognition of dual objectives reflects the evolution of central banking philosophy in India.

The RBI Act establishes the institutional structure of the Reserve Bank, including its capital structure, management framework, and operational powers. According to the statutory provisions, the Reserve Bank’s affairs are managed by a Central Board of Directors, which exercises all powers and performs all functions of the Bank. The Act also establishes Local Boards for specific regions, each comprising five members appointed by the Central Government for a maximum term of four years. The governance structure ensures both centralized policy-making and regional representation in the Bank’s operations.

One of the most significant provisions relates to the Bank’s exclusive authority over currency issuance. The Act grants the Reserve Bank exclusive rights to issue currency notes in India, with detailed provisions governing note design, denominations, and legal tender status. The maximum denomination permitted under the Act is specified, and comprehensive procedures are established for the exchange of damaged or imperfect notes. These provisions ensure orderly currency management and maintain public confidence in the monetary system.

The Reserve Bank’s role as banker to the government represents another critical function established under the Act. The Bank conducts banking affairs for the Central Government, manages public debt, and handles the operational aspects of government borrowing. The debt management policy aims at minimizing borrowing costs, reducing rollover risk, smoothening maturity structures, and improving the depth and liquidity of government securities markets through active secondary market development.

The Banking Regulation Act, 1949

The Banking Regulation Act, 1949 represents the principal regulatory statute governing banking companies in India [2]. Originally enacted as the Banking Companies Act, 1949, it came into force on March 16, 1949, and was subsequently renamed as the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 with effect from March 1, 1966. The Act initially applied only to banking companies but was amended in 1965 to extend its provisions to cooperative banks, significantly expanding its regulatory scope.

The Act defines “banking” to mean “the accepting, for the purpose of lending or investment, of deposits of money from the public, repayable on demand or otherwise, and withdrawable by cheque, draft, order or otherwise.” This definitional framework establishes the essential characteristics that distinguish banking activities from other forms of financial intermediation. The Act further defines “banking company” as any company engaged in the banking business in India, thereby establishing the regulatory perimeter for its application.

Under the statutory framework, no company can use the words “bank,” “banker,” or “banking” as part of its name or in connection with its business unless it is a banking company. Similarly, no company can carry on banking business in India unless it uses at least one of these words as part of its name. These naming requirements serve important public policy objectives by preventing misleading representations and ensuring that only properly licensed and regulated entities can hold themselves out as banks.

The Act establishes detailed requirements for minimum capital, reserve funds, and paid-up capital that banking companies must maintain. Banking companies operating in India must comply with specified capital adequacy requirements based on their places of business and operational scope. The Reserve Bank has the authority to prescribe the form and manner in which capital and reserves must be maintained, ensuring that banks maintain adequate financial strength to support their operations and protect depositor interests.

Provisions relating to the management and operations of banking companies occupy a substantial portion of the Act. Banking companies must have a whole-time chairman who may be appointed on either a full-time or part-time basis. The Act prohibits common directors across different banking companies, preventing conflicts of interest and ensuring independent governance. Banking companies incorporated in India cannot have any person serving as a director who also serves on the board of another banking company. Furthermore, no banking company can have more than three directors who collectively are entitled to exercise voting rights exceeding ten percent in companies among themselves.

The Act grants the Reserve Bank extensive supervisory and regulatory powers over banking companies. The RBI can inspect any banking company and its books and accounts, inquire into the affairs of the company, and direct banks to take specific actions in the public interest, in the interest of banking policy, or in the interest of depositors. These powers enable the central bank to maintain effective oversight of the banking sector and intervene when necessary to protect financial stability.

A 2020 amendment brought cooperative banks comprehensively under the supervision of the Reserve Bank of India [3]. This amendment brought 1,482 urban cooperative banks and 58 multi-state cooperative banks under RBI supervision, addressing long-standing concerns about regulatory gaps in the cooperative banking sector. The amendment empowers the RBI to reconstruct or merge cooperative banks without imposing moratoriums, providing additional tools for addressing distressed institutions.

The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002

The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, commonly known as the SARFAESI Act, represents a landmark legislation addressing non-performing assets in the banking sector [4]. This Act empowers banks and financial institutions to recover non-performing assets without court intervention, significantly expediting the recovery process and strengthening the rights of secured creditors.

The Act allows banks and financial institutions to auction residential or commercial properties of defaulters to recover loans, though agricultural land remains exempt from its provisions. The statutory framework provides three primary methods for recovery of non-performing assets: asset securitisation, asset reconstruction, and enforcement of security interests. Each method offers distinct mechanisms for addressing distressed assets and recovering outstanding dues.

Under the enforcement provisions, when a borrower defaults on repayment and their account is classified as a non-performing asset by the secured creditor, the creditor may repossess the security asset by written notice before the expiry of the limitation period. The secured creditor must issue a written notice to the borrower requiring discharge of liabilities within sixty days from the date of notice. If the borrower fails to discharge the liability within the specified period, the secured creditor may take possession of the secured asset and proceed with its sale or lease.

The Act established the framework for Asset Reconstruction Companies, which can acquire financial assets from banks and financial institutions and issue security receipts to qualified institutional buyers. The first Asset Reconstruction Company of India, ARCIL, was established under this Act. By virtue of the SARFAESI Act, the Reserve Bank of India has the authority to register and regulate Asset Reconstruction Companies, ensuring that these entities operate within proper supervisory frameworks.

The constitutional validity of the SARFAESI Act was upheld by the Supreme Court of India in the landmark judgment of Mardia Chemicals Ltd. v. Union of India [5]. In this case decided on April 8, 2004, the Supreme Court declared that the Act does not violate the Constitution and provides secured creditors with legitimate mechanisms for recovering their dues. The Court held that borrowers may appeal against lenders in the Debt Recovery Tribunal without having to deposit seventy-five percent of the debt amount, balancing creditor rights with borrower protections. This judgment established important principles regarding the constitutionality of non-judicial recovery mechanisms and the scope of borrower remedies under the Act.

The 2016 amendments to the SARFAESI Act introduced significant changes to strengthen the recovery process. The Enforcement of Security Interest and Recovery of Debts Laws and Miscellaneous Provisions (Amendment) Act, 2016 granted banks and Asset Reconstruction Companies the power to convert debt into equity shares of the defaulting company. This debt-to-equity conversion mechanism provides additional flexibility in restructuring distressed assets and potentially recovering value through ownership stakes rather than merely liquidating assets.

The Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation Act, 1961

The Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation Act, 1961 establishes the framework for protecting depositors and guaranteeing credit facilities [6]. This Act came into force on January 1, 1962, creating the Deposit Insurance Corporation, which was later merged with the Credit Guarantee Corporation of India Ltd. to form the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation in 1978.

The Act mandates that the DICGC insures all bank deposits including savings, fixed, current, and recurring deposits for up to a specified limit per depositor in a bank. The insurance coverage limit has been progressively increased over the years, with the most recent increase raising the limit from one lakh rupees to five lakh rupees with effect from February 4, 2020. This enhanced coverage provides greater protection to depositors and strengthens public confidence in the banking system.

The statutory definition of “deposit” under the Act means “the aggregate of the unpaid balances due to a depositor in respect of all his accounts by whatever name called,” thereby including fixed deposits and accrued interest within its ambit. The insurance cover applies to deposits held by a depositor “in the same right and same capacity” at all branches of an insured bank taken together, ensuring that depositors receive appropriate protection regardless of how many branches they maintain accounts with.

A significant amendment was introduced through the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (Amendment) Act, 2021, which came into force with effect from September 1, 2021 [7]. This amendment inserted a new Section 18A enabling depositors to receive easy and time-bound access to their deposits through interim payments by DICGC in cases where restrictions are imposed on banks under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. When banks are placed under “All Inclusive Directions” by the RBI, DICGC becomes liable to make interim payments to depositors up to the deposit insurance cover within ninety days of imposition of such directions. This provision ensures that depositors can access their funds even when banks face operational restrictions, providing crucial liquidity support during periods of financial distress.

Regulatory Powers and Administrative Framework

Reserve Bank of India’s Supervisory Authority

The Reserve Bank of India exercises comprehensive supervisory and regulatory authority over the Indian banking system through powers conferred by multiple statutes. These powers enable the RBI to maintain financial stability, protect depositor interests, and ensure the soundness of individual banks and the banking system as a whole. The supervisory framework encompasses licensing, prudential regulation, inspection, and enforcement actions.

The licensing function represents a fundamental regulatory power whereby the RBI controls entry into the banking sector. No entity can commence banking business without obtaining a license from the Reserve Bank. The licensing process involves detailed scrutiny of the applicant’s capital adequacy, management competence, ownership structure, and business plan. This gatekeeping function ensures that only financially sound and well-managed entities enter the banking sector, protecting the integrity of the financial system.

Prudential regulations issued by the RBI govern critical aspects of banking operations including capital adequacy requirements, asset classification norms, provisioning standards, exposure limits, and risk management frameworks. These regulations establish minimum standards that banks must maintain to ensure their financial soundness and ability to absorb losses. The Basel capital adequacy framework has been progressively implemented in India, with banks required to maintain minimum capital ratios calculated according to prescribed methodologies.

The inspection function enables the RBI to examine banks’ operations, assess their financial condition, and identify emerging risks. The Reserve Bank conducts both on-site examinations and off-site surveillance, analyzing banks’ financial statements, regulatory returns, and operational data. Inspection findings inform supervisory assessments and may trigger enforcement actions when deficiencies or violations are identified.

When banks fail to comply with regulatory requirements or face financial difficulties, the RBI can exercise various enforcement powers. These include issuing directions to banks, removing managerial personnel, superseding boards of directors, imposing penalties, and in extreme cases, placing banks under moratorium or initiating liquidation proceedings. These graduated enforcement measures enable the RBI to address problems at early stages while retaining stronger tools for dealing with severe situations.

Monetary Policy Framework

The monetary policy framework underwent significant reforms with amendments to the Reserve Bank of India Act establishing a formal Monetary Policy Committee. The statutory framework recognizes that “it is essential to have a modern monetary policy framework to meet the challenge of an increasingly complex economy” and mandates that “the primary objective of the monetary policy is to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth.”

The Monetary Policy Committee consists of six members, including the Governor of the Reserve Bank who serves as the Chairperson, a Deputy Governor nominated by the Governor, one official selected by the Board, and three external members appointed by the Central Government. This composition balances institutional expertise with external perspectives, enhancing the credibility and effectiveness of monetary policy decisions.

The Committee meets at least four times per year, with the meeting schedule published at least one week before the first meeting. Decisions are taken by majority vote, with each member having one vote, and the Governor having a casting vote in case of a tie. The transparency requirements include publishing minutes of meetings and maintaining public accountability for policy decisions, fostering public understanding and confidence in the monetary policy process.

Judicial Interpretations and Landmark Cases

Constitutional Validity and Bank Nationalization

The landmark case of R.C. Cooper v. Union of India decided in 1969 represents a seminal judgment addressing bank nationalization and fundamental rights [8]. This case arose from the government’s decision to nationalize fourteen major commercial banks through the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Ordinance, 1969. The petitioners challenged the ordinance on grounds that it violated their fundamental rights to property and freedom to conduct business.

The Supreme Court examined whether the nationalization violated Article 19 relating to freedom to practice any profession or carry on any occupation, trade or business, and Article 31 concerning the right to property. The Court developed the “effect test” to determine whether a law that ostensibly regulates property actually amounts to acquisition, examining the real impact rather than merely the stated purpose of the legislation.

The majority opinion held that the ordinance was unconstitutional because it failed to provide adequate compensation as required under Article 31. The Court emphasized that even when pursuing legitimate policy objectives like socialism and equitable distribution of resources, the government must respect constitutional safeguards protecting fundamental rights. This decision led to the enactment of the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertaking) Act, 1970, which addressed the constitutional deficiencies identified by the Court.

The judgment expanded the scope of Article 31 while examining its relationship with Article 19, establishing important principles regarding the protection of property rights and the extent of permissible state intervention in the economy. The case also became the basis for subsequent landmark judgments including Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala and Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, which further developed constitutional jurisprudence regarding fundamental rights.

Enforcement of Security Interests

The Supreme Court has delivered numerous judgments clarifying the scope and application of the SARFAESI Act. These decisions have established important principles regarding the rights of secured creditors, borrower remedies, and the interaction between the SARFAESI Act and other legal frameworks. The judicial interpretations have generally upheld the constitutionality of the Act while ensuring that borrower rights receive adequate protection.

In cases involving the enforcement of security interests, courts have emphasized that the SARFAESI Act provides a legitimate mechanism for secured creditors to recover their dues without lengthy court proceedings. However, the courts have also recognized that borrowers retain the right to challenge the enforcement actions by filing applications before Debt Recovery Tribunals. The tribunals can grant stay orders and provide appropriate relief when enforcement actions are shown to be unjustified or procedurally defective.

The Supreme Court has clarified that the SARFAESI Act’s provisions do not contain any embargo on the category of persons to whom mortgaged property can be sold by banks for realization of their dues. The Act’s provisions prevail over state laws that might impose restrictions on property transfers, reflecting the principle that central legislation enacted for the benefit of the banking system takes precedence over potentially conflicting state enactments.

Depositor Protection and Banking Regulation

Judicial pronouncements have reinforced the importance of depositor protection within the regulatory framework. In K. Sashidhar v. Indian Overseas Bank decided in 2021, the Supreme Court held that banks cannot arbitrarily freeze customer accounts without notice and an opportunity to be heard, as such actions would violate customers’ property rights and due process protections. This judgment establishes important procedural safeguards preventing arbitrary banking actions that could harm customers.

The courts have also addressed the regulatory powers of the Reserve Bank of India, generally upholding broad supervisory authority while ensuring that regulatory actions remain within statutory limits. In HDFC Bank Ltd. v. Union of India, the Supreme Court established that banks are entitled to file writ petitions under Article 32 of the Constitution against directions issued by the Reserve Bank of India, ensuring that regulatory actions remain subject to judicial review when they allegedly violate constitutional rights.

Challenges and Contemporary Developments

The Indian banking system continues to evolve in response to changing economic conditions, technological innovations, and emerging risks. Non-performing assets remain a persistent challenge, requiring coordinated efforts by banks, regulators, and the government to strengthen recovery mechanisms and improve credit discipline. The insolvency and bankruptcy framework has been strengthened through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, which provides an additional mechanism for addressing corporate distress and recovering bank dues.

Digital banking and financial technology innovations are transforming the delivery of banking services, creating both opportunities and regulatory challenges. The Reserve Bank of India has issued various guidelines and frameworks to govern digital payments, mobile banking, and fintech partnerships, balancing innovation with prudential concerns and consumer protection. Cybersecurity risks have assumed greater importance as banking systems become increasingly digitized, requiring enhanced security measures and incident response capabilities.

Climate-related financial risks are emerging as a new area of regulatory focus, with the Reserve Bank beginning to incorporate environmental, social, and governance considerations into its supervisory framework. Banks are being encouraged to develop frameworks for assessing and managing climate risks in their lending and investment activities, recognizing that environmental factors can materially affect credit quality and financial stability.

The cooperative banking sector remains an area requiring continued attention, despite the recent regulatory reforms bringing cooperative banks under RBI supervision. Governance weaknesses, operational inefficiencies, and capital constraints continue to affect many cooperative banks, necessitating capacity building and institutional strengthening efforts. The regulatory framework must balance the unique characteristics of cooperative institutions with the need for prudential oversight and depositor protection.

Conclusion

The Indian banking system operates under a sophisticated legal and regulatory framework that has evolved over decades to address changing economic conditions and financial sector challenges. The statutory architecture established through the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, the SARFAESI Act, 2002, and related legislation provides comprehensive authority for regulating banking operations, protecting depositors, and maintaining financial stability. Judicial interpretations have further refined these statutory provisions, balancing the rights of various stakeholders and ensuring that regulatory actions remain within constitutional bounds. As the banking sector continues to evolve, the legal and regulatory framework must adapt to address emerging challenges while preserving the core principles of financial stability, depositor protection, and efficient credit intermediation that underpin a sound banking system.

References

[1] Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. India Code. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2398/1/a1934-2.pdf

[2] Banking Regulation Act, 1949. India Code. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1885/1/A194910.pdf

[3] Banking Regulation Act, 1949 – Amendments. Reserve Bank of India. Available at: https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/BANKI15122014.pdf

[4] Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002. India Code. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2006/1/A2002-54.pdf

[5] Landmark Judgments on Banking Laws [2022] Part I. SCC Online. Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/03/22/landmark-judgments-on-banking-laws-2022-part-i/

[6] Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation Act, 1961. India Code. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1655/5/a1961-47.pdf

[7] Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation – About Us. DICGC. Available at: https://www.dicgc.org.in/sites/default/files/2024-11/About%20Us_final.pdf

[8] R.C. Cooper v. Union of India: Bank Nationalisation Case. iPleaders. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/r-c-cooper-v-union-india-bank-nationalisation-case-case-summary/

[9] SARFAESI Act, 2002 – Applicability and Process. ClearTax. Available at: https://cleartax.in/s/sarfaesi-act-2002

Whatsapp

Whatsapp