Individual Insolvency Under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC)

Introduction

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 represents a watershed moment in India’s insolvency jurisprudence, establishing a unified legislative framework to address financial distress among corporate entities, individuals, and partnership firms. While much attention has focused on corporate insolvency under Part II of the statute, Part III addresses insolvency resolution and bankruptcy for individuals and partnership firms, representing an equally significant yet underutilized aspect of the legislative framework. This system aims to provide honest but unfortunate debtors with mechanisms for financial rehabilitation while protecting creditor interests through transparent and time-bound processes. The individual insolvency provisions under the IBC recognize that financial distress among natural persons requires distinct treatment from corporate insolvency, necessitating sensitivity to human dignity, livelihood considerations, and prospects for economic rehabilitation.

Legislative Evolution and Constitutional Foundation

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) received Presidential assent on May 28, 2016, consolidating and amending laws relating to insolvency resolution for companies, partnership firms, and individuals [1]. Prior to this enactment, individual insolvency was governed primarily by the Presidency Towns Insolvency Act, 1909 and the Provincial Insolvency Act, 1920, both archaic statutes reflecting colonial-era approaches to debt recovery that lacked emphasis on debtor rehabilitation. The Bankruptcy Law Reforms Committee, chaired by T.K. Viswanathan, submitted its report in November 2015, proposing a modern insolvency framework drawing on international best practices while adapting to Indian economic and social realities. The Committee recognized that individual insolvency provisions must balance multiple objectives including providing honest debtors with fresh starts, preventing abuse by strategic defaulters, ensuring adequate creditor recovery, and maintaining credit discipline within the economy.

Part III of the IBC extends to personal guarantors to corporate debtors, partnership firms and proprietorship firms, and individuals other than personal guarantors. However, these provisions remained unnotified for several years after the enactment of the principal statute. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs issued a notification on November 15, 2019, bringing into force provisions of Part III specifically concerning personal guarantors to corporate debtors [2]. This selective notification reflected the government’s strategy of phased implementation, prioritizing the resolution of guarantor insolvency given its immediate relevance to non-performing assets in the banking sector. The constitutional validity of this selective notification was subsequently upheld by the Supreme Court in Lalit Kumar Jain v. Union of India, where the Court recognized the legislative objective behind phased implementation and rejected contentions that selective notification exceeded governmental powers [3].

Structure of Part III of the IBC: Individual Insolvency Framework

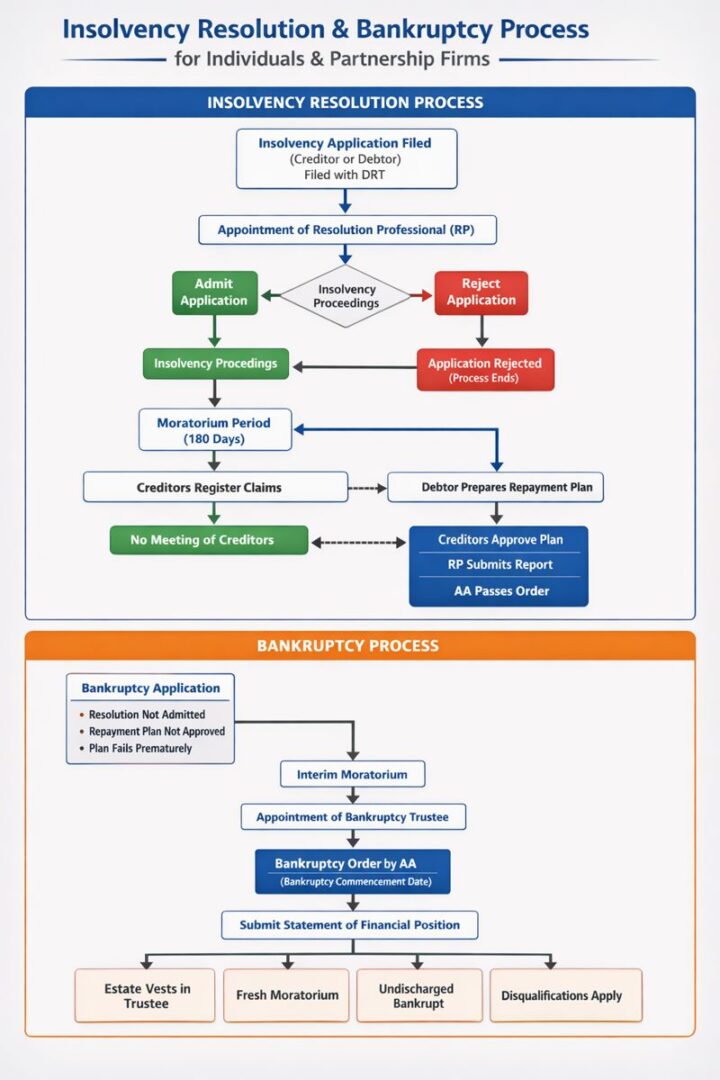

Part III of the IBC comprises seven chapters establishing a layered framework for individual insolvency. Chapter I contains preliminary provisions including definitions and applicability. Chapter II prescribes the Fresh Start Process, a simplified mechanism for discharge of qualifying debts by low-income individuals meeting specified thresholds. Chapter III establishes the Insolvency Resolution Process for individuals, providing a structured mechanism for debt restructuring through repayment plans negotiated with creditors. Chapter IV addresses bankruptcy orders for individuals and partnership firms when resolution efforts fail. Chapter V governs administration and distribution of the bankrupt’s estate. Chapter VI designates the Debt Recovery Tribunal as the adjudicating authority for individual insolvency matters, except for personal guarantors to corporate debtors whose matters lie before the National Company Law Tribunal. Chapter VII prescribes offenses and penalties for violations of individual insolvency provisions.

The Code distinguishes between financial creditors, operational creditors, secured creditors, and unsecured creditors, though Part III does not create the same categorical distinctions found in Part II regarding corporate insolvency. The definition of creditor under Section 3(10) applies uniformly across the Code, meaning any person to whom debt is owed, including financial creditors, operational creditors, secured creditors, unsecured creditors, and decree holders. This inclusive definition ensures that all categories of creditors can participate in individual insolvency proceedings, though their rights and priorities differ depending on the nature of their claims.

Fresh Start Process: Providing a Second Chance

The Fresh Start Process constitutes one of the most progressive features of individual insolvency law, designed specifically for persons who owe relatively modest amounts and possess minimal assets to repay their debts. Section 80 establishes eligibility criteria for this mechanism, requiring that the debtor’s gross annual income does not exceed sixty thousand rupees, the aggregate value of assets does not exceed twenty thousand rupees, and the aggregate value of qualifying debts does not exceed thirty-five thousand rupees [4]. Additionally, the debtor must not own any dwelling unit or agricultural land, no fresh start process or insolvency resolution process must be subsisting against them, and no previous fresh start order must have been made in relation to them in the preceding twelve months. These stringent thresholds were derived from the Socio-Economic and Caste Census 2011 data, reflecting the economic profile of the poorest sections of Indian society. However, these thresholds have remained static since the Code’s enactment, raising concerns about their continued relevance given inflation and income growth over the intervening years.

Qualifying debts under Section 79(19) include amounts due along with interest or any other sum due, excluding certain categories of excluded debts. Excluded debts comprise amounts payable under court decrees, debts incurred through fraud or misrepresentation, student loans unless the loan has been outstanding for seven years or repayment would impose undue hardship, debts arising from liability to pay maintenance, and debts which have been incurred within three months prior to the application for fresh start process. This exclusion framework ensures that certain socially important obligations remain enforceable while providing relief from commercial debts that prevent economic rehabilitation.

The procedural framework for fresh start begins with the filing of an application under Section 81, which triggers an interim moratorium from the date of filing. This interim moratorium stays all legal proceedings against the debtor in respect of any debt and prohibits creditors from initiating new proceedings until the application is admitted or rejected. The application must contain prescribed information supported by affidavit, including a list of all debts with amounts due and creditor details, interest payable and rates stipulated in contracts, lists of security held against debts, financial information of the debtor and immediate family for the preceding two years, personal details and reasons for the application, details of pending legal proceedings, and confirmation that no previous fresh start order has been issued in the preceding twelve months.

Upon receiving the application, the Debt Recovery Tribunal appoints a resolution professional who must scrutinize the application within ten days and recommend acceptance or rejection. The resolution professional examines whether the debtor satisfies eligibility criteria, verifies the accuracy of information provided, and assesses whether the debtor has acted in good faith. If the resolution professional recommends acceptance and the Tribunal admits the application under Section 84, a moratorium commences covering all debts mentioned in the application. During the moratorium period, the debtor faces certain restrictions under Section 85, including prohibitions on acting as a company director, participating in company management, entering into financial transactions above specified values without disclosure, traveling outside India without permission, and various other activities designed to prevent dissipation of assets or incurring additional debts.

The resolution professional prepares a final list of qualifying debts after considering creditor claims and objections, which the Tribunal considers before issuing a discharge order. The discharge relieves the debtor from liability to pay qualifying debts, effectively providing a fresh start. However, the resolution professional can seek revocation of the fresh start order under Section 91 if the debtor’s financial circumstances change such that they become ineligible, if the debtor violates restrictions imposed during the process, or if the debtor acts in a mala fide manner willfully failing to comply with Code provisions.

Insolvency Resolution Process for Individuals

Where the Fresh Start Process applies only to low-income debtors with minimal debts and assets, Chapter III establishes the Insolvency Resolution Process for individuals who do not qualify for fresh starts but seek to avoid bankruptcy through negotiated debt restructuring. This process can be initiated either by the debtor under Section 94 or by creditors under Section 95. When a debtor initiates the process, they must demonstrate inability to pay debts and must not have undergone fresh start, insolvency resolution, or bankruptcy proceedings in the preceding twelve months. When creditors initiate the process, they must first deliver a demand notice under Section 95(4) calling upon the debtor to repay the unpaid debt within specified time. If the debtor fails to make payment, creditors can file an application seeking initiation of insolvency resolution.

Section 96 provides for an interim moratorium from the date of filing until admission or rejection of the application, mirroring the protection available in fresh start proceedings. Upon admission of the application, the Tribunal appoints a resolution professional who takes control of the debtor’s estate and assets. The resolution professional invites claims from creditors, prepares a list of creditors and their claims, and facilitates negotiations aimed at developing a repayment plan acceptable to both the debtor and creditors.

The resolution professional must complete the insolvency resolution process within one hundred and eighty days from the commencement date, extendable by a further ninety days. During this period, the debtor and creditors negotiate a repayment plan that may involve debt restructuring, extended payment schedules, partial debt forgiveness, or other arrangements that maximize creditor recovery while providing the debtor with a viable path to solvency. The repayment plan requires approval by a specified majority of creditors by value of claims and must be sanctioned by the Tribunal under Section 114.

If no repayment plan is approved within the prescribed timeline or if an approved plan is subsequently violated, the Tribunal may pass a bankruptcy order under Section 121, triggering the bankruptcy process for individuals. This transition from resolution to bankruptcy reflects the Code’s recognition that not all financial distress can be resolved through negotiation and that formal bankruptcy proceedings become necessary when compromise proves impossible.

Bankruptcy for Individuals and Partnership Firms

Chapter IV addresses bankruptcy orders and their consequences when insolvency resolution fails. Upon passing a bankruptcy order, the Tribunal appoints a bankruptcy trustee who takes custody and control of the bankrupt’s estate. The bankruptcy trustee’s role encompasses realizing assets, distributing proceeds among creditors according to the prescribed priority waterfall, and administering the bankruptcy process until discharge. The bankrupt faces various disabilities during bankruptcy, including restrictions on obtaining credit above specified thresholds without disclosure, acting as company director or participating in management, traveling abroad without permission, and engaging in certain business activities.

The Code prescribes a detailed framework for administration and distribution of the bankrupt’s estate under Chapter V. Section 149 and subsequent provisions establish that the bankruptcy trustee must identify and take possession of all assets forming part of the estate, realize these assets through sale or other disposition, and distribute the proceeds to creditors according to statutory priority. Secured creditors enjoy priority regarding assets subject to their security interests, while unsecured creditors share proportionately in any surplus after satisfaction of secured claims and specified preferential debts.

Discharge from bankruptcy typically occurs after a specified period during which the bankrupt complies with obligations imposed by the Tribunal and the bankruptcy trustee. Upon discharge, the individual is released from liability for debts included in the bankruptcy proceeding, subject to certain exceptions for debts that survive bankruptcy such as maintenance obligations, student loans, and debts arising from fraud. The discharge enables the former bankrupt to re-enter economic life without the burden of pre-bankruptcy debts, effectuating the rehabilitative purpose underlying modern bankruptcy law.

Personal Guarantors to Corporate Debtors

The notification of November 15, 2019 bringing Part III provisions into force specifically for personal guarantors to corporate debtors reflected the pressing need to address guarantee enforcement in the context of rising corporate defaults. Section 5(22) defines personal guarantor as an individual who is the surety in a contract of guarantee to a corporate debtor. The liability of personal guarantors derives from Section 128 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, which establishes that the surety’s liability is co-extensive with that of the principal debtor. This co-extensive nature means the guarantor’s obligation runs parallel to rather than subsequent to the principal debtor’s liability, enabling creditors to proceed against guarantors without first exhausting remedies against the principal debtor [5].

The constitutional validity of individual insolvency provisions under IBC concerning personal guarantors was challenged in numerous writ petitions consolidated before the Supreme Court. Petitioners contended that Sections 95 to 100 violated principles of natural justice by allegedly condemning personal guarantors unheard and vesting excessive powers in resolution professionals. In Dilip B. Jiwrajka v. Union of India, decided on November 9, 2023, the Supreme Court dismissed these contentions and upheld the constitutionality of the impugned provisions [6]. The Court clarified that resolution professionals function as facilitators rather than adjudicators, their role being to scrutinize applications, verify eligibility, and recommend acceptance or rejection to the Tribunal. The Tribunal retains exclusive adjudicatory authority, ensuring compliance with principles of natural justice through opportunities for hearing and reasoned orders.

The question of whether discharge of a corporate debtor through approved resolution plans automatically discharges personal guarantors generated significant litigation. The Supreme Court in Lalit Kumar Jain v. Union of India definitively held that approval of a resolution plan does not per se discharge the guarantor’s liability [7]. The Court reasoned that the Indian Contract Act distinguishes between voluntary and involuntary discharge of principal debtors. Sections 133 through 141 of the Contract Act specify circumstances warranting guarantor discharge, including voluntary releases, composition agreements, or creditor conduct impairing surety rights. However, discharge through operation of law, such as insolvency proceedings or liquidation, does not automatically absolve the guarantor whose obligation arises from an independent contract. This interpretation aligns with established jurisprudence recognizing the co-extensive yet independent nature of guarantee obligations.

Subsequent decisions reinforced this position. In State Bank of India v. Mahendra Kumar Jajodia, the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal held that creditors can initiate insolvency resolution proceedings against personal guarantors without any pending corporate insolvency resolution process or liquidation proceedings against the corporate debtor [8]. The Supreme Court upheld this ruling, confirming that simultaneous or independent proceedings against guarantors are permissible. This position recognizes practical realities where corporate debtors may lack assets sufficient for creditor recovery, making guarantor assets essential for meaningful debt resolution. The jurisdiction for personal guarantor insolvency lies with the National Company Law Tribunal having territorial jurisdiction over the corporate debtor’s registered office, rather than the Debt Recovery Tribunal which handles other individual insolvency matters, reflecting the intimate connection between corporate debtor insolvency and guarantor liability.

Adjudicating Authority and Appellate Framework

Chapter VI of the IBC designates adjudicating authorities for individual insolvency matters. Section 179 specifies that the Debt Recovery Tribunal established under the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 serves as the adjudicating authority for individuals and partnership firms. However, Section 60 provides that where corporate insolvency resolution or liquidation proceedings against a corporate debtor are pending before the National Company Law Tribunal, applications relating to insolvency resolution or bankruptcy of personal guarantors to that corporate debtor shall be filed before the same National Company Law Tribunal. This jurisdictional allocation ensures coordination between related proceedings and prevents forum shopping or conflicting determinations.

Appeals from orders of the Debt Recovery Tribunal lie to the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal under Section 202, while appeals from National Company Law Tribunal orders concerning personal guarantors lie to the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal under Section 61. Further appeals on substantial questions of law lie to the Supreme Court. This appellate structure provides multiple layers of judicial scrutiny while maintaining specialized expertise in insolvency matters at the tribunal level. The Code prescribes time limits for disposing of appeals at various levels, reflecting the emphasis on expeditious resolution that pervades the entire legislative scheme.

Offenses, Penalties, and Compliance Framework

Chapter VII of the IBC establishes offenses and penalties for violations of individual insolvency provisions. Section 184 penalizes false representations or fraud in connection with insolvency proceedings, recognizing that the effectiveness of insolvency processes depends on accurate disclosure and honest conduct by debtors. Section 185 addresses concealment of property or documents, failure to deliver property or books to the resolution professional or bankruptcy trustee, and other conduct designed to defeat creditor rights. Section 186 penalizes creditors who make false claims or produce false proofs of debt, ensuring that creditors cannot abuse insolvency processes to extract payments exceeding legitimate entitlements.

These penal provisions complement the civil remedies available under the Code, creating a robust deterrent against abuse by either debtors or creditors. However, the Code recognizes that many instances of individual financial distress result from misfortune rather than misconduct. The legislative framework thus seeks to distinguish between honest but unfortunate debtors deserving of fresh starts and strategic defaulters who abuse insolvency mechanisms. This distinction pervades the eligibility criteria, disclosure requirements, and compliance obligations throughout Part III.

Challenges and Implementation Concerns

Despite the progressive framework established by Part III of the IBC, significant implementation challenges have hindered effective operationalization of individual insolvency provisions. The restrictive eligibility thresholds for fresh start have attracted sustained criticism from commentators who observe that even the poorest sections of Indian society may fail to qualify given current income and debt levels. The sixty thousand rupee annual income threshold, twenty thousand rupee asset ceiling, and thirty-five thousand rupee debt limit were derived from 2011 census data and have not been adjusted for inflation or economic growth since the Code’s enactment. Research suggests that these static thresholds render the fresh start mechanism accessible to an extremely limited population, potentially defeating its intended purpose of providing widespread debt relief to vulnerable individuals.

The non-notification of Part III provisions beyond personal guarantors to corporate debtors has created an anomalous situation where partnership firms, proprietorship firms, and individuals other than personal guarantors cannot access the insolvency resolution and bankruptcy mechanisms established by the Code. These categories of debtors remain subject to the archaic Presidency Towns Insolvency Act and Provincial Insolvency Act, both of which lack the modern rehabilitative features characterizing the Code. The Insolvency Law Committee Report 2020 recognized this gap and recommended comprehensive notification of Part III, but implementation has not occurred.

The procedural framework for personal guarantors raises specific concerns regarding simultaneous proceedings against corporate debtors and their guarantors. Critics argue that allowing creditors to proceed simultaneously against both principal debtors and guarantors creates possibilities for double recovery, particularly where resolution plans approved for corporate debtors do not adequately account for amounts already recovered from guarantors. While the co-extensive liability doctrine provides legal justification for parallel proceedings, practical mechanisms ensuring proper accounting and preventing unjust enrichment require further development. The interim moratorium provisions have also drawn scrutiny, with contentions that imposing moratoriums immediately upon application filing without prior adjudication or notice to guarantors potentially violates natural justice principles, though these contentions were rejected by the Supreme Court in the Dilip B. Jiwrajka judgment.

International Comparisons and Best Practices

Examining international personal insolvency frameworks provides instructive comparisons highlighting potential improvements for Indian law. The United Kingdom operates a sophisticated personal insolvency system featuring Debt Relief Orders for low-income individuals with debts below thirty thousand pounds and minimal assets. These thresholds are periodically revised to reflect economic conditions, unlike the static thresholds in the Indian Code. The UK system also provides Individual Voluntary Arrangements enabling debt restructuring over five years through negotiations facilitated by insolvency practitioners. Bankruptcy in the UK typically results in discharge after one year for compliant bankrupts, substantially shorter than discharge periods in many jurisdictions and reflecting policy emphasis on rehabilitation over punishment.

The United States bankruptcy system under the Bankruptcy Code provides Chapter 7 liquidation for individuals seeking discharge of debts upon liquidation of non-exempt assets, and Chapter 13 reorganization enabling wage earners to develop plans repaying debts over three to five years. Generous exemption regimes allow debtors to retain essential assets including homesteads up to specified values, vehicles, household goods, and tools of trade, recognizing that effective fresh starts require debtors to maintain minimum living standards and earning capacity. Automatic stay provisions immediately halt all collection activities upon bankruptcy filing, providing comprehensive relief from creditor pressure during reorganization efforts.

These international models share common themes including periodic revision of eligibility thresholds, generous exemptions preserving essential assets, relatively short discharge periods for compliant debtors, and comprehensive stays preventing creditor harassment. The Indian framework could benefit from incorporating these features through periodic threshold adjustments tied to inflation indices, expanded exemption categories protecting essential assets, clarified discharge timelines, and enhanced monitoring of debtor compliance to ensure that only good faith debtors benefit from rehabilitative provisions.

Future Directions and Reform Imperatives

The path forward for individual insolvency law in India requires addressing multiple dimensions of current deficiencies. First, the Central Government should notify the remaining provisions of Part III, extending insolvency resolution and bankruptcy mechanisms to partnership firms, proprietorship firms, and all categories of individuals. This comprehensive notification would fulfill the legislative intent of providing uniform insolvency treatment across all debtor categories while retiring the obsolete colonial-era statutes that currently govern most individual insolvency.

Second, eligibility thresholds for the Fresh Start Process require immediate revision and should be indexed to inflation or per capita income measures ensuring periodic automatic adjustment. The Bankruptcy Law Reforms Committee recommended that thresholds should increase at regular intervals aligned with Consumer Price Index movements, a recommendation that remains unimplemented. Raising thresholds to reflect current economic realities would extend fresh start benefits to broader segments of the population facing genuine financial distress.

Third, procedural frameworks governing personal guarantor insolvency require refinement to address concerns about simultaneous proceedings and accounting for amounts recovered from multiple sources. Clear rules specifying how creditor recoveries from corporate debtors affect claims against personal guarantors would prevent double recovery while respecting the co-extensive liability doctrine. The Code could prescribe that creditors must account for amounts recovered through corporate insolvency resolution when calculating claims against personal guarantors, ensuring that total recovery does not exceed the original debt plus permitted costs and interest.

Fourth, institutional capacity building remains essential for effective implementation. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India must develop regulations, forms, and guidance materials facilitating smooth operation of individual insolvency processes. Training programs for resolution professionals handling individual cases should emphasize the human dimensions of personal insolvency, distinguishing these proceedings from corporate insolvency in terms of sensitivity to debtor welfare and family circumstances. Debt Recovery Tribunals and National Company Law Tribunals require adequate resources and personnel to handle anticipated caseloads as individual insolvency provisions achieve full operationalization.

Fifth, public awareness campaigns explaining individual insolvency options and processes would enable eligible debtors to access relief mechanisms. Many individuals experiencing financial distress lack awareness of legal options available for debt restructuring or discharge. Civil society organizations, consumer protection agencies, and financial literacy programs should disseminate information about insolvency processes, eligibility criteria, and procedures for seeking relief.

Conclusion

The individual insolvency framework under Part III of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) represents a forward-looking legislative initiative aimed at providing honest but unfortunate debtors with pathways to financial rehabilitation while maintaining appropriate protections for creditor rights. The Fresh Start Process offers streamlined debt discharge for low-income individuals, the Insolvency Resolution Process enables negotiated debt restructuring for those with greater means and debts, and the bankruptcy framework provides for orderly liquidation and distribution when resolution proves impossible. The specific provisions addressing personal guarantors to corporate debtors reflect recognition of guarantee liability’s importance in the Indian credit market and the need for effective mechanisms enabling creditors to access guarantor assets when corporate debtors default.

However, significant challenges impede full realization of Part III’s potential. Restrictive eligibility thresholds, incomplete notification, procedural complexities, and limited institutional capacity have constrained the impact of individual insolvency provisions. International experience demonstrates that effective personal insolvency systems require regular threshold adjustments, generous exemptions preserving essential assets, expedited discharge for compliant debtors, and strong institutional infrastructure supporting timely case resolution.

Addressing these deficiencies through comprehensive notification of remaining provisions, threshold revisions, procedural refinements, capacity building, and public awareness initiatives would transform individual insolvency from a nascent legal construct into a functional mechanism providing meaningful relief to distressed debtors. Such transformation would serve both individual welfare and broader economic efficiency by enabling productive individuals to recover from financial setbacks, reducing the stigma associated with financial distress, promoting entrepreneurship by mitigating fear of permanent debt bondage, and channeling resources away from hopeless collection efforts toward productive economic activities. The individual insolvency framework thus stands at a critical juncture where thoughtful reforms and committed implementation can fulfill the rehabilitative vision underlying the IBC.

References

[1] The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (Act No. 31 of 2016). Available at: https://ibbi.gov.in/uploads/legalframwork/547c9c2af074c90ac5919fa8a5c60bd4.pdf

[2] Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Notification dated November 15, 2019, bringing Part III provisions into force for personal guarantors to corporate debtors. Available at: https://www.mca.gov.in/

[3] Lalit Kumar Jain v. Union of India, (2021) ibclaw.in 61 SC. Available at: https://ibclaw.in/analysis-of-initiation-of-insolvency-proceedings-against-personal-guarantors-in-light-of-lalit-kumar-vs-union-of-india-by-ms-nandini-shenai-mr-miheer-jain/

[4] Section 80, Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016. Available at: https://ibclaw.in/section-80-eligibility-for-making-an-application/

[5] State Bank of India, Stressed Asset Management Branch v. Mahendra Kumar Jajodia, (2022) ibclaw.in 32 SC. Available at: https://ibclaw.in/supreme-court-personal-guarantors-can-be-made-liable-under-insolvency-code-prior-to-any-action-against-principal-borrower/

[6] Dilip B. Jiwrajka v. Union of India, decided November 9, 2023. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/law-firms/law-firm-articles-/supreme-court-personal-guarantors-ibc-presidency-towns-insolvency-act-cirp-nclat-resolution-professional-248885

[7] Lalit Kumar Jain v. Union of India, (2021) ibclaw.in 61 SC. Available at: https://www.mondaq.com/india/insolvencybankruptcy/1072832/personal-guarantors-to-corporate-debtors-liable-under-the-ins olvency-and-bankruptcy-code-2016-supreme-court-of-india

[8] State Bank of India v. Mahendra Kumar Jajodia, NCLAT judgment upheld by Supreme Court. Available at: https://www.acmlegal.org/blog/supreme-courts-ruling-on-the-validity-of-provisions-of-personal-guarantors-under-the-insolvency-and-bankruptcy-code/

[9] Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India, Working Group Report on Individual Insolvency (June 2017). Available at: https://ibbi.gov.in/Agenda_9_210917.pdf

Authorized by: Rutvik Desai

Whatsapp

Whatsapp