Probate, Letter of Administration and Succession Certificate: Legal Framework and Judicial Interpretation in India

\

\

Introduction

The Indian legal system provides a structured framework for dealing with the property and assets of deceased individuals through three primary legal instruments: Probate, Letter of Administration and Succession Certificate. These mechanisms, primarily governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925[1], ensure orderly transmission of property rights while protecting the interests of legal heirs, creditors, and other stakeholders. Understanding the distinctions between these instruments, their applicability, and the legal procedures involved is essential for anyone dealing with estate matters in India. This article examines the legislative provisions, regulatory requirements, and judicial interpretations that shape the law of succession in contemporary India.

Probate: Definition and Legal Framework

Statutory Definition

Probate is defined under Section 2(f) of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, as “the copy of a will certified under the seal of a court of competent jurisdiction with a grant of administration to the estate of the testator.”[1] This judicial certification serves a dual purpose: it validates the authenticity of the will and grants authority to the executor to administer the deceased’s estate. Through the probate process, courts verify that the document presented is indeed the last will and testament of the deceased, executed in accordance with legal requirements.

Mandatory Requirements for Probate

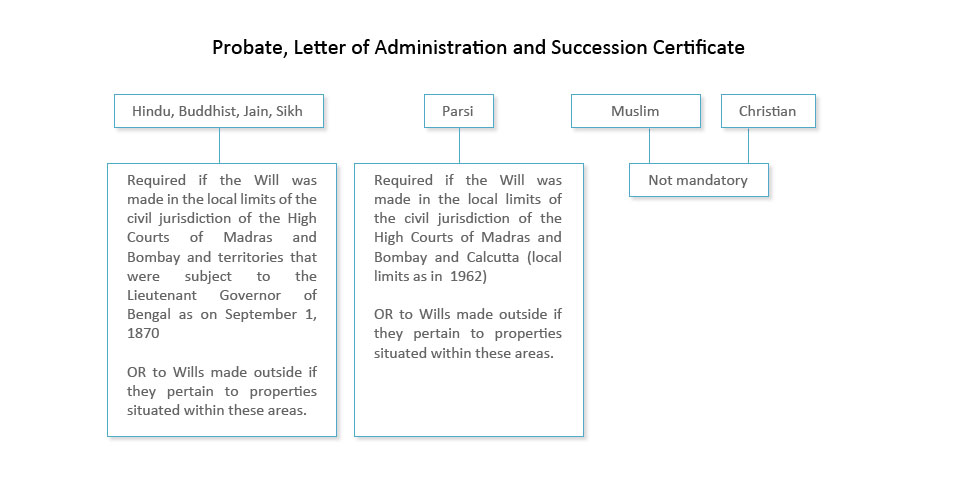

Section 213 of the Indian Succession Act establishes that no right as executor or legatee can be established in any court unless probate has been granted by a competent court.[1] However, this requirement is not universal. The provision contains significant exceptions that reflect India’s religious and regional diversity. According to Section 213(2) read with Section 57, probate is mandatory only in specific circumstances. For instance, wills made by Muslims and Indian Christians are exempted from the probate requirement. For Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains, probate is mandatory only for wills executed within the ordinary original civil jurisdiction of the High Courts at Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay (now Kolkata, Chennai, and Mumbai).[1]

Who May Apply for Probate

The law places certain restrictions on who may be granted probate. Section 223 of the Indian Succession Act clearly states that probate cannot be granted to any person who is a minor or of unsound mind.[2] This safeguard ensures that only individuals with legal capacity can undertake the responsibility of administering an estate. Furthermore, the provision extends this restriction to associations of individuals unless they constitute a company satisfying prescribed conditions.

Letter of Administration: Legal Provisions and Application

Nature and Purpose

A Letter of Administration serves a similar function to probate but applies in different circumstances. This document is obtained from courts by legal heirs when the deceased has died intestate, meaning without leaving a valid will. The critical distinction lies in the source of authority: while probate validates a will and empowers the executor named therein, a Letter of Administration derives its authority directly from the court’s grant, appointing an administrator to manage the estate.

Circumstances Requiring Letter of Administration

Section 234 of the Indian Succession Act governs situations where a Letter of Administration becomes necessary.[2] These include cases where the deceased left a will but did not appoint an executor, or where the appointed executor refuses to act, has become incapable of acting, or cannot be located. In such scenarios, the court grants administration rights to individuals who would have been entitled to administer the estate had the deceased died intestate. This provision ensures that estates are not left in administrative limbo due to the absence or incapacity of an appointed executor.

Rights Conferred by Letter of Administration

Section 212 of the Indian Succession Act establishes that no right to any property of a person who has died intestate can be established in any court unless letters of administration have been granted by a court of competent jurisdiction.[3] Once granted, the Letter of Administration entitles the administrator to all rights belonging to the intestate as effectively as if administration had been granted immediately upon death. The administrator assumes responsibilities similar to those of an executor, including paying debts, distributing assets, and representing the estate in legal proceedings.

Succession Certificate: Scope and Limitations

Legal Definition and Purpose

A Succession Certificate is a specialized document issued by courts to facilitate the collection of debts and securities belonging to a deceased person. Unlike probate and letters of administration, which grant broad administrative powers over an entire estate, a Succession Certificate has a more limited scope. It specifically authorizes the holder to collect debts owed to the deceased and to deal with securities such as bonds, debentures, and shares.

Statutory Restrictions

Section 370 of the Indian Succession Act contains important restrictions on when Succession Certificates may be granted.[4] The provision explicitly states that a Succession Certificate cannot be granted with respect to any debt or security to which a right must be established by letters of administration or probate under Sections 212 or 213. This means that if the deceased left a will, the estate must be administered through probate or letters of administration rather than a Succession Certificate. The restriction prevents circumvention of the more rigorous probate process and ensures that testamentary wishes are properly honored.

Effect and Protection

Section 381 of the Indian Succession Act defines the legal effect of a Succession Certificate.[4] The certificate provides conclusive protection to parties paying debts or dealing with securities specified therein. It affords full indemnity to persons making payments in good faith to the certificate holder, even if the certificate was granted in contravention of Section 370 or contains other defects. This protection encourages banks, companies, and other institutions to release funds and transfer securities without fear of later claims, thereby facilitating the administration of estates.

Comparative Analysis and Practical Distinctions

Testamentary versus Intestate Succession

The fundamental difference between these instruments lies in whether the deceased left a valid will. Probate applies exclusively to testamentary succession, where the deceased has executed a will designating beneficiaries and, typically, an executor. Letters of Administration apply both to intestate succession and to situations where a will exists but no executor was appointed or the appointed executor cannot act. Succession Certificates, while applicable to intestate estates, are limited to debts and securities rather than the entire estate.

Scope of Authority

Probate and Letters of Administration confer broad administrative authority over the deceased’s entire estate, including immovable property, movable assets, debts, and securities. The holder can represent the estate in legal proceedings, pay creditors, and distribute assets to beneficiaries. In contrast, Succession Certificates authorize only the collection of specific debts and securities listed in the certificate. They do not confer rights over immovable property or general administrative powers.

Jurisdictional Variations

The requirement for probate varies significantly based on geography and religious community. Within the former presidencies of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, probate requirements are more stringent. Outside these areas, many communities can establish rights under a will without obtaining probate, though doing so may still be advisable for practical reasons such as dealing with banks or transferring property.

Procedural Requirements and Court Practice

Petition and Documentation

Section 276 of the Indian Succession Act prescribes that applications for probate or letters of administration must be made by petition distinctly written in English or the language ordinarily used in proceedings before the court.[1] The petition must be accompanied by the will or authenticated copies thereof, along with evidence establishing the death of the testator, the authenticity of the will, and the petitioner’s right to apply. Courts may require additional documentation depending on the complexity of the estate and the presence of competing claims.

Verification and Investigation

Courts exercise summary jurisdiction in matters of Succession Certificates but conduct more thorough investigations for probate and letters of administration. The testamentary court must satisfy itself regarding the validity of the will, the testator’s mental capacity at the time of execution, and the absence of fraud, coercion, or undue influence. Section 61 of the Indian Succession Act explicitly provides that wills obtained through fraud, coercion, or undue influence are void.[3] Courts typically require attestation by at least two witnesses who saw the testator sign or affix their mark to the will, as mandated by Section 63.

Judicial Interpretation: Landmark Judgments

Banarsi Dass v. Teeku Dutta (2005)

The Supreme Court’s decision in Banarsi Dass v. Teeku Dutta addressed fundamental questions about the scope of inquiry in succession certificate proceedings and the use of scientific evidence.[5] In this case, the appellant contested the grant of a Succession Certificate, arguing that DNA testing should be ordered to establish whether the applicant was truly the deceased’s daughter. The trial court had initially ordered DNA testing, but the High Court set aside this order.

The Supreme Court upheld the High Court’s decision, establishing several important principles. First, it clarified that the grant of a Succession Certificate does not establish the title of the grantee as heir of the deceased but merely furnishes authority to collect debts and allows debtors to make payments without risk. Second, the Court emphasized that DNA tests should not be ordered routinely in succession proceedings. Such tests are appropriate only in exceptional circumstances where conventional evidence is insufficient and the test would serve a legitimate purpose. The Court noted that succession proceedings involve limited inquiry and that parties should prove their claims through oral and documentary evidence rather than creating evidence through scientific testing.

Practical Implications

This judgment has significant implications for succession practice. It reinforces the principle that Succession Certificates serve a limited protective function rather than definitively resolving questions of inheritance rights. Parties dissatisfied with the grant of a certificate must pursue their claims through regular civil suits where broader factual inquiry is possible. The decision also reflects judicial caution about ordering invasive procedures that may infringe on personal dignity and privacy without compelling justification.

Interaction with Personal Laws

Hindu Succession Act, 1956

While the Indian Succession Act provides the general framework for succession, personal laws govern intestate succession for various religious communities. The Hindu Succession Act, 1956, determines inheritance rights for Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs dying intestate. This Act establishes a hierarchy of heirs and rules for distribution that differ significantly from the Indian Succession Act’s provisions. However, the procedural mechanisms of probate, letters of administration, and Succession Certificates remain relevant even for these communities when dealing with wills or requiring court authorization to collect debts.

Muslim Personal Law

Muslim succession is governed by personal law rather than the Indian Succession Act, except for matters of testamentary succession where Muslim law permits bequests up to one-third of the estate. Probate is not required for Muslim wills under Section 213(2) of the Indian Succession Act. However, Succession Certificates may still be useful for Muslim heirs needing to collect debts or deal with securities, as they provide statutory protection to paying parties.

Regulatory Compliance and Administrative Practice

Banking and Financial Institutions

Financial institutions typically require production of probate, letters of administration, or Succession Certificates before releasing deposits, transferring securities, or closing accounts of deceased customers. These requirements serve both legal and practical purposes. Legally, institutions protect themselves from future claims by other potential heirs. Practically, these documents provide clear evidence of who has authority to deal with the deceased’s assets. Section 215 of the Indian Succession Act provides that grant of probate or letters of administration supersedes any previously granted Succession Certificate, giving priority to the more authoritative documents.

Property Registration

Transfer of immovable property following death requires appropriate succession documents. While Succession Certificates explicitly do not extend to immovable property, probate or letters of administration are generally required for registration of property transfers. State registration departments typically maintain specific requirements regarding the documents they will accept for mutation of property records and registration of transmission of title.

Contemporary Challenges and Reforms

Delays and Backlog

One significant challenge in succession law administration is the delay in obtaining necessary court orders. Probate and administration proceedings can take months or years, particularly when disputes arise or documentation is incomplete. This delay creates hardship for families needing to access assets for living expenses or business continuity. Some courts have established dedicated succession cells to expedite processing, but significant backlogs remain in many jurisdictions.

Digital Assets and Modern Securities

The rise of digital assets, cryptocurrency, and dematerialized securities raises questions about how traditional succession mechanisms apply. While Section 370 defines securities broadly enough to encompass modern forms through state government notification, practical challenges remain in identifying and accessing digital assets. Legal practitioners increasingly recommend that individuals maintain comprehensive asset inventories and provide necessary access information to executors.

Conclusion

Probate, Letters of Administration, and Succession Certificates form essential components of India’s succession law framework, each serving distinct purposes within a carefully structured legal regime. The Indian Succession Act, 1925, as interpreted by courts over decades, provides clear guidance on when each instrument is appropriate and what authority it confers. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for legal practitioners, financial institutions, and families navigating the complex process of administering estates. While the fundamental statutory framework remains robust, ongoing challenges related to delays, modern assets, and the intersection of multiple legal systems suggest areas where continued evolution and reform may be necessary to ensure that succession law serves contemporary needs effectively.

References

[1] The Indian Succession Act, 1925. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2385

[2] S.S. Rana & Co. (2023). “Probate, Letter of Administration, and Succession Certificate.” Available at: https://ssrana.in/articles/probate-letter-of-administration-succession-certificate/

[3] Sarin Advocate. “Probate of a Will – Indian Succession Act 1925.” Available at: https://sites.google.com/site/sarinadvocate/indian-succession-act-1925/probate-of-a-will

[4] iPleaders (2022). “Succession Certificate – All You Need to Know.” Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/all-you-need-to-know-about-succession-certificate/

[5] Banarsi Dass v. Teeku Dutta (Mrs) and Anr., Civil Appeal No. 2918 of 2005, Supreme Court of India (2005). Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/505918/

[6] The Legal Quotient (2022). “Letter of Administration Under the Indian Succession Act.” Available at: https://thelegalquotient.com/family-laws/indian-succession-act/letter-of-administration/138/

[7] Indian Kanoon. “Section 370 in The Indian Succession Act, 1925.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1494917/

[8] LegalServiceIndia. “Succession Certificate.” Available at: https://www.legalservicesindia.com/article/1182/Succession-Certificate.html

[9] Yellow (2024). “Indian Succession Act 1925: Understanding Succession Laws In India.” Available at: https://www.getyellow.in/resources/indian-succession-act-1925-understanding-succession-laws-in-india

Whatsapp

Whatsapp