Understanding Criminal Trial Procedure in Indian Law

(Note: This is an article written for layman having no knowledge of law. If you are a lawyer or a legal expert, please feel free to point out if there is any mistake in the article. If you want to give your inputs to make this better, please leave a comment at the bottom.)

(Note: This is an article written for layman having no knowledge of law. If you are a lawyer or a legal expert, please feel free to point out if there is any mistake in the article. If you want to give your inputs to make this better, please leave a comment at the bottom.)

The criminal justice system in India operates through a structured framework that balances the rights of the accused with the interests of society. Understanding the criminal trial procedure in India is essential to comprehending how this balance is maintained and how justice is delivered through the judiciary. At the heart of this framework lies the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, which provides a detailed roadmap for how criminal cases progress from the moment an offense is reported until a final judgment is delivered. This procedural law ensures that justice is not only done but is seen to be done, maintaining public confidence in the judicial system. The criminal trial procedure in India is designed to ensure that every accused person receives a fair hearing while the state pursues legitimate interests in prosecuting crime and maintaining social order.

Classification of Criminal Trials

The Criminal Procedure Code divides criminal trials into distinct categories based on the severity of offenses and the corresponding punishment they attract. This classification is fundamental to understanding the criminal trial procedure in India, as it determines which court will hear the case, what procedures will be followed, and how expeditiously the matter should be resolved. The three primary types are warrant cases, summons cases, and summary trials, each serving a specific purpose in the broader criminal justice landscape.

Warrant Cases: Handling Serious Offenses

Warrant cases represent the most serious category of criminal offenses under Indian law. According to Section 2(x) of the Criminal Procedure Code, a warrant case relates to any offense punishable with death, imprisonment for life, or imprisonment exceeding two years [1]. The designation “warrant case” stems from the fact that in such serious matters, the court may issue a warrant for the arrest of the accused rather than merely summoning them to appear.

The trial procedure for warrant cases is outlined in Chapter XIX of the Code, spanning Sections 238 to 250. The procedure differs depending on whether the case has been instituted on a police report or through a private complaint. When a case is instituted on a police report, the magistrate must first comply with Section 207, which requires supplying the accused with copies of the police report and related documents. After considering these documents and hearing both the prosecution and the accused, the magistrate determines whether there is sufficient ground to proceed with the case. If the magistrate finds no prima facie case, the accused may be discharged at this preliminary stage itself.

In cases instituted otherwise than on a police report, the magistrate must first hear the prosecution and examine the evidence presented. This ensures that frivolous or malicious complaints do not result in protracted trials. Only after satisfying himself that there is sufficient ground to proceed does the magistrate frame charges against the accused. The framing of charges in a warrant case must be done in writing, clearly specifying the offense with which the accused is charged. This written charge serves as the foundation for the entire trial that follows.

An important procedural safeguard in warrant cases is the requirement under Section 193 that a Sessions Court cannot take cognizance of any offense as a court of original jurisdiction unless the case has been committed to it by a Magistrate [2]. This provision ensures that serious cases undergo preliminary scrutiny before reaching the higher court. The process of committal serves as a filter, preventing the Sessions Court from being burdened with cases that lack merit while simultaneously protecting the accused from being subjected to a Sessions Court trial without adequate justification.

Summons Cases: Streamlined Procedures for Lesser Offenses

By definition under Section 2(w) of the Criminal Procedure Code, summons cases encompass all offenses that are not warrant cases. In practical terms, these are cases relating to offenses punishable with imprisonment of two years or less [3]. The distinction is significant because summons cases follow a considerably simplified procedure compared to warrant cases, reflecting the less serious nature of the offenses involved.

The trial procedure for summons cases is detailed in Chapter XX, covering Sections 251 to 259. When the accused appears before the magistrate in a summons case, the particulars of the offense are stated to him orally, and he is asked whether he pleads guilty or has any defense to make. Notably, it is not necessary to frame a formal charge in a summons case, which expedites the proceedings considerably. This dispensation with formal charges does not mean that the accused is left uninformed; rather, the substance of the accusation must be clearly communicated, ensuring the accused understands what he is being called upon to answer.

If the accused pleads guilty, the magistrate has the discretion to convict him based on that plea alone. The law even permits the accused to plead guilty in absentia by transmitting a letter containing his plea along with the fine amount specified in the summons. This provision, found in Section 253, demonstrates the flexibility built into the system for dealing with minor offenses where the accused acknowledges his guilt and is willing to accept the consequences.

An important provision in summons trial procedure is Section 259, which empowers the magistrate to convert a summons case into a warrant case if, during the course of the trial, it appears that in the interests of justice, the offense should be tried according to the more elaborate warrant case procedure. This conversion mechanism ensures that cases initially perceived as minor but later revealed to be more serious can receive the appropriate level of judicial scrutiny.

Summary Trials: Swift Justice for Petty Offenses

Summary trials represent the most expedited form of criminal adjudication under Indian law. These trials are designed to deal swiftly with petty offenses, thereby reducing the burden on the judiciary and ensuring that minor matters do not clog the system. The legal framework for summary trials is found in Chapter XXI, covering Sections 260 to 265 of the Criminal Procedure Code [4].

Section 260 delineates which cases may be tried summarily. These include offenses not punishable with death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment exceeding two years. Additionally, specific offenses like theft under Sections 379, 380, or 381 of the Indian Penal Code where the stolen property value does not exceed two thousand rupees can be tried summarily. The Chief Judicial Magistrate, Metropolitan Magistrate, or any Magistrate of the first class specially empowered by the High Court possesses the authority to conduct summary trials.

The procedure followed in summary trials mirrors that of summons cases, as prescribed by Section 262. However, a crucial limitation exists: no sentence of imprisonment exceeding three months can be passed in any conviction under this chapter. This restriction ensures that even though the procedure is expedited, the punishment remains proportionate to the simplified process. The court must record the substance of the evidence and provide a brief statement of its findings along with reasons in the judgment.

The rationale behind summary trials is clear: expeditious disposal of cases helps maintain the efficiency of the criminal justice system while still affording the accused a fair opportunity to present his case. However, the accused is not without recourse; he retains the right to request that his case be tried according to regular procedures if he believes the summary process does not adequately serve the interests of justice in his particular circumstances.

Pre-Trial Proceedings: From FIR to Charge Sheet

Before a criminal trial can commence, several crucial Procedure must be completed. These pre-trial stages serve multiple purposes: they initiate the criminal justice machinery, allow for investigation of the alleged offense, and provide preliminary evaluation of whether there is sufficient evidence to proceed to trial. Understanding these stages is essential to comprehending how cases move through the system.

Registration of First Information Report

The First Information Report, commonly known as FIR, marks the starting point of criminal proceedings in cognizable offenses. Section 154 of the Criminal Procedure Code mandates that every information relating to the commission of a cognizable offense, if given orally to an officer in charge of a police station, shall be reduced to writing [5]. The officer must read over the information to the informant, who then signs it, and its substance must be entered in a book maintained in the prescribed form.

The importance of the FIR cannot be overstated. It serves as the foundation for the entire investigation and subsequent trial. In Lalita Kumari v. State of Uttar Pradesh, the Supreme Court held that registration of an FIR is mandatory when information discloses commission of a cognizable offense, and no preliminary inquiry is permissible in such situations [6]. This landmark judgment curtailed the discretion of police officers to refuse registration of FIRs, thereby strengthening the rights of complainants.

The FIR need not be a detailed account of the entire incident; rather, it should contain sufficient information to set the criminal law in motion. It establishes the time at which information about the offense first reached the police, which can be crucial for evaluating subsequent developments in the case. Importantly, a copy of the FIR must be provided to the informant free of cost, as mandated by Section 154(2), ensuring transparency in the process.

Investigation: Gathering Evidence

Following the registration of an FIR, the investigation phase begins. This is when the police collect evidence, examine witnesses, inspect the scene of the crime, and generally attempt to ascertain whether an offense has indeed been committed and, if so, by whom. The investigation is governed by Sections 154 to 173 of the Criminal Procedure Code, which outline the powers and duties of investigating officers.

During investigation, the police have extensive powers including the authority to examine witnesses, search premises with or without warrant depending on circumstances, seize material objects that may serve as evidence, and arrest suspects. However, these powers are subject to important limitations designed to protect individual rights. For instance, statements made to police officers during investigation cannot be used as evidence at trial, though they may be used to contradict or corroborate the witness if he testifies during trial.

The investigation culminates in either the filing of a charge sheet or a closure report. If the investigating officer concludes that sufficient evidence exists to proceed against the accused, he files a charge sheet under Section 173. The charge sheet is not merely a list of charges; it is a document that contains the results of the investigation, including details of the offense, the role of each accused person, the evidence collected, and the sections of law under which the accused are proposed to be charged. If, however, the investigation reveals insufficient evidence or establishes that no offense was committed, a closure report is filed before the court.

Framing of Charges: Defining the Accusation

Once the charge sheet has been filed and the magistrate has determined that a prima facie case exists, the next critical step is the framing of charges. This stage serves multiple important functions: it informs the accused of the precise accusation he must meet, it defines the scope of the trial, and it provides the accused an opportunity to plead guilty if he so chooses.

In warrant cases, charges must be framed in writing as per Sections 211 to 224 of the Code. The charge should contain such particulars as to the time and place of the alleged offense, and the person against whom the offense was committed, as are reasonably sufficient to give the accused notice of the matter he is called upon to answer. The importance of proper charge framing cannot be understated, as defects in charges can lead to acquittal if they cause prejudice to the accused.

When charges are framed and read out to the accused, he is asked whether he pleads guilty or claims to be tried. If he pleads guilty, the court may convict him based on that plea, though it must satisfy itself that the plea was made voluntarily and the accused understands its consequences. If the accused claims to be tried, the trial proceeds to the evidence stage. Importantly, if the court finds that no offense is made out against the accused at this stage, it has the power to discharge him before the trial even begins, preventing unnecessary litigation.

Trial Proceedings: Examination of Evidence and Arguments

The trial stage represents the culmination of the criminal trial procedure in India, where all the evidence collected during investigation is presented before the court, witnesses are examined, and arguments are heard. This is where the adversarial nature of the Indian criminal justice system becomes most apparent, with the prosecution seeking to prove the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt, while the defense attempts to create reasonable doubt or establish innocence.

Recording of Prosecution Evidence

After charges have been framed, the prosecution bears the burden of proving its case. This is done through the presentation of evidence, which typically consists of witness testimony and documentary or material evidence. The witnesses called by the prosecution, known as prosecution witnesses, are examined in court. Their initial testimony is called examination-in-chief, during which the prosecution elicits testimony supporting its case.

The evidence presented must be relevant and admissible under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Documents produced before the court and accepted by it are marked as exhibits, each assigned a unique identification for record-keeping purposes. Material objects recovered during investigation, such as weapons allegedly used in the crime, are also produced and marked as exhibits. The prosecution must establish the chain of custody for such objects to ensure their integrity.

A significant challenge in criminal trials arises when prosecution witnesses turn hostile. A hostile witness is one who, despite being called by the prosecution, gives testimony that contradicts or fails to support the prosecution’s case. When a witness turns hostile, the prosecution may seek the court’s permission to cross-examine that witness, treating him as though he were called by the opposite party. The phenomenon of witnesses turning hostile is unfortunately common in the Indian criminal justice system and poses serious challenges to the effective prosecution of crimes.

Cross-Examination and Defense Evidence

Following examination-in-chief, the defense has the right to cross-examine prosecution witnesses. Cross-examination is a powerful tool that serves multiple purposes: it tests the credibility of witnesses, exposes inconsistencies or contradictions in their testimony, and brings out facts favorable to the defense that may not have emerged during examination-in-chief. The right to cross-examination is considered so fundamental that denial of this right can vitiate the entire trial.

After the prosecution closes its case, the court examines the accused under Section 313 of the Criminal Procedure Code. This provision serves a unique purpose in Indian criminal procedure. Unlike in many other jurisdictions, the examination under Section 313 is not conducted under oath, and the accused cannot be compelled to answer questions. The purpose is to give the accused an opportunity to explain incriminating circumstances appearing in the evidence against him [7].

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that the examination under Section 313 is not a mere formality but a substantial right of the accused. In Naresh Kumar v. State of Delhi, the Court held that failure to question the accused about incriminating circumstances constitutes a material irregularity that may vitiate the conviction [8]. The court must put all incriminating material to the accused and give him a fair chance to explain, though the accused’s explanation need not be on oath and cannot be used as substantive evidence against him.

Following the Section 313 examination, the defense may present its own evidence. This might include defense witnesses who testify about facts favorable to the accused, or documentary evidence supporting the defense theory. However, in practice, the defense often chooses not to lead evidence, relying instead on the principle that the burden of proof lies entirely on the prosecution. The prosecution must prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt, and if it fails to do so, the accused is entitled to acquittal regardless of whether he has offered any evidence in his defense.

Final Arguments and Judgment

Once all evidence has been recorded, both sides present their final arguments. The prosecution goes first, summarizing its case, highlighting the evidence that establishes guilt, and addressing any weaknesses in its case or strengths in the defense case. The defense then presents its arguments, pointing out gaps in the prosecution evidence, highlighting inconsistencies in witness testimony, and arguing why the prosecution has failed to prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

After hearing final arguments, the court reserves judgment or may pronounce it immediately depending on the complexity of the case. The judgment must contain a clear finding on each charge, along with the reasons for that finding. If the accused is convicted, a separate hearing on sentence follows in cases of serious offenses. During the arguments on sentence, both sides present submissions on what punishment should be awarded, considering factors such as the gravity of the offense, the circumstances in which it was committed, the criminal history of the accused, and the potential for reformation.

The final judgment with sentence represents the culmination of the trial. In pronouncing sentence, courts in India consider multiple theories of punishment. The deterrent theory emphasizes punishment severe enough to deter both the offender and others from committing similar crimes. The reformative theory focuses on rehabilitating the offender and reintegrating him into society. Courts must strike a balance between these competing considerations while ensuring that the sentence is proportionate to the offense and the offender’s circumstances.

Judicial Hierarchy and Jurisdiction

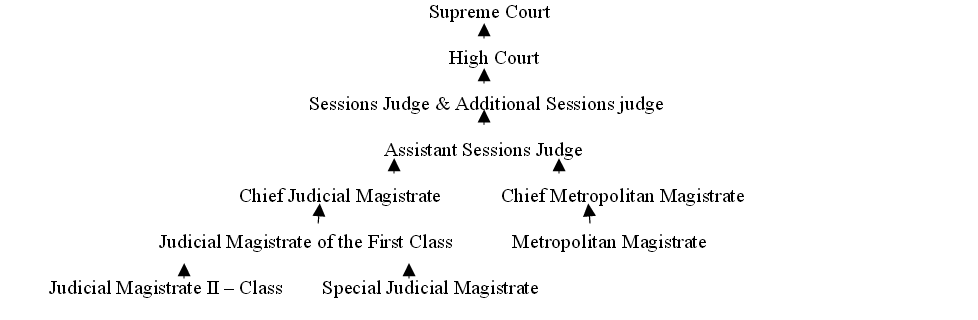

Understanding the criminal trial procedure requires familiarity with the hierarchy of criminal courts in India and their respective jurisdictions. At the lowest level are the Magistrates’ Courts, divided into Chief Judicial Magistrates, Additional Chief Judicial Magistrates, and Judicial Magistrates of the First and Second Class. These courts handle the vast majority of criminal cases, including all summons cases and warrant cases where the offense is punishable with imprisonment up to seven years.

For more serious offenses punishable with imprisonment exceeding seven years, life imprisonment, or death, jurisdiction lies with the Sessions Court. However, as discussed earlier, the Sessions Court cannot take cognizance directly; cases must be committed to it by a Magistrate. Above the Sessions Courts sit the High Courts, which exercise appellate and revisional jurisdiction over lower courts, and at the apex stands the Supreme Court of India, the highest court of appeal in criminal matters.

The jurisdictional framework ensures that cases are heard at appropriate levels based on their seriousness. It also provides multiple tiers of review, allowing errors or injustices at lower levels to be corrected through appeals and revisions. This multilayered structure is fundamental to ensuring fairness and maintaining public confidence in the criminal justice system.

Conclusion

The criminal trial Procedure in India represents a carefully calibrated balance between competing interests: the state’s interest in prosecuting crime and maintaining social order, the rights of the accused to a fair trial and the presumption of innocence, and society’s interest in seeing justice done expeditiously and transparently. The procedural framework established by the Criminal Procedure Code, enriched by judicial interpretation over decades, provides the structure within which this balance is maintained.

From the initial registration of an FIR through investigation, filing of charge sheet, framing of charges, trial, and finally judgment, each stage of the criminal trial procedure in India serves specific purposes and is governed by detailed procedural requirements. While the system is not without its challenges, including delays in trial, witness protection issues, and problems with hostile witnesses, the fundamental framework remains sound. Periodic amendments to the Code and progressive judicial interpretation continue to refine the criminal trial procedure in India, addressing emerging challenges while preserving core principles of justice and fairness that have guided Indian criminal law since independence.

References

[1] Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, Section 2(x). Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/15247

[2] Drishti Judiciary. (2024). Cognizance by Sessions Courts – Section 193 CrPC. Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/to-the-point/bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhita-&-code-of-criminal-procedure/cognizance-by-sessions-courts-section-193-crpc

[3] Rest The Case. (2024). Types of Trials in CrPC: A Complete Guide. Available at: https://restthecase.com/knowledge-bank/types-of-trial-in-crpc

[4] iPleaders. (2022). Summary Trial under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/summary-trial-code-criminal-procedure-1973/

[5] iPleaders. (2022). Section 154 CrPC. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/section-154-crpc/

[6] Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. (2020). Handbook of Landmark Judgments on Human Rights and Policing in India. Available at: https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/download/1619069016Human%20Rights%20Judgments%20on%20Human%20Rights%20and%20Policing%20in%20India.pdf

[7] Drishti Judiciary. (2024). Section 313 of CrPC. Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/current-affairs/section-313-of-crpc

[8] Drishti Judiciary. (2024). Non-Examination of Accused under Section 313 of CrPC. Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/current-affairs/non-examination-of-accused-under-section-313-of-crpc

[9] Rest The Case. (2024). CrPC Section 193 – Cognizance Of Offences By Courts Of Session. Available at: https://restthecase.com/knowledge-bank/crpc/section-193

Whatsapp

Whatsapp