Intestate Succession in India: Understanding Inheritance When There Is No Will

When an individual passes away without creating a valid will, their estate does not simply vanish or become ownerless. Instead, a complex legal framework governs how their assets will be distributed among surviving family members. This process, known as intestate succession, operates differently depending on the deceased person’s religion, domicile, and personal circumstances. In India, where personal laws based on religious identity continue to shape family matters, understanding these distinctions becomes crucial for anyone concerned about their family’s financial future.

The Concept of Intestate Succession

Intestate succession refers to the distribution of a deceased person’s property when they have not left behind a legally valid will. The term “intestate” literally means “without a testament,” and such situations trigger specific legal provisions that determine who inherits what portion of the estate. Unlike testamentary succession where the deceased exercises autonomy over asset distribution, intestate succession follows predetermined statutory schemes that aim to provide for family members according to established legal hierarchies.

The rationale behind intestate succession laws stems from the legislature’s attempt to approximate what a reasonable person would have wanted for their family. These laws reflect societal norms about family structures and obligations, though they may not always align with an individual’s actual preferences. This gap between statutory distribution and personal wishes underscores why estate planning through will-making remains advisable for most people.

Religious Personal Laws and Succession

India’s pluralistic legal system maintains separate succession frameworks for different religious communities. Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Parsis, and Jews each have distinct succession laws, while those who do not fall under any specific religious category are governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925[1]. This diversity reflects the constitutional promise to respect religious and cultural practices while gradually moving toward uniformity in certain aspects of personal law.

Hindu Succession: The Hindu Succession Act, 1956

The Hindu Succession Act, 1956[2] governs intestate succession for Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs. This legislation underwent significant amendment in 2005 to address gender discrimination that had persisted in inheritance rights. The Act establishes detailed classifications of heirs and specifies their respective shares in the deceased’s property.

When a Hindu male dies intestate, his property devolves according to the rules specified in Section 8 of the Hindu Succession Act. The property first goes to Class I heirs, which includes the widow, children, and mother of the deceased. If a Hindu man dies leaving behind a wife, two sons, and a daughter, each Class I heir receives an equal share. The 2005 amendment was particularly transformative for daughters, granting them rights as coparceners in Hindu Undivided Family property equal to those of sons, overturning centuries of patriarchal inheritance practices.

The Supreme Court’s judgment in Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma[3] clarified that daughters’ coparcenary rights exist by birth, irrespective of whether the father was alive on the date of the 2005 amendment. This progressive interpretation extended equal inheritance rights retroactively, affirming that daughters born before 2005 also possess these rights if the property remains undivided.

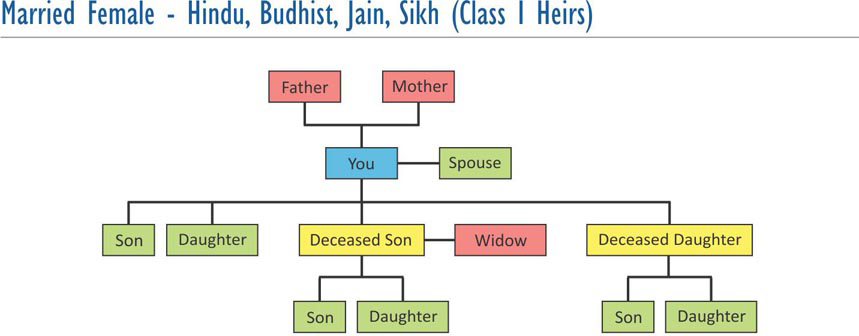

For Hindu females dying intestate, Section 15 of the Hindu Succession Act provides a different succession scheme. Her property first devolves upon her sons and daughters (including children of predeceased children), then to her husband, followed by her parents. If none of these heirs exist, the property passes to her husband’s heirs and finally to her parents’ heirs. This dual-track approach reflects historical distinctions between self-acquired property and property inherited from relatives.

Parsi Succession Under the Indian Succession Act

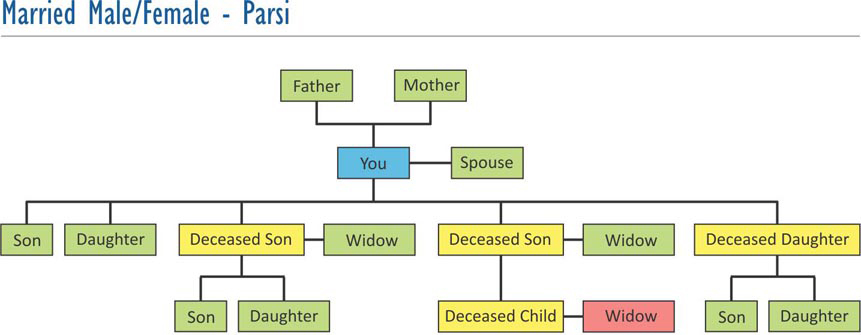

Parsis in India are governed by Part V of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which contains special provisions for this community[1]. When a Parsi dies intestate leaving a widow and children, the widow receives a share equal to that of each child. If there are children but no widow, the children inherit the entire estate in equal shares.

The Act provides detailed rules for various family configurations. If a Parsi dies leaving a widow but no lineal descendants, and the estate’s net value does not exceed one lakh rupees, the widow inherits the entire property. For estates exceeding this value, the widow receives one-half, with the remaining distributed among the deceased’s parents or, if they are deceased, among his siblings. These provisions reflect a balance between protecting the spouse’s interests and maintaining connections with the natal family.

Christian Succession: Indian Succession Act Provisions

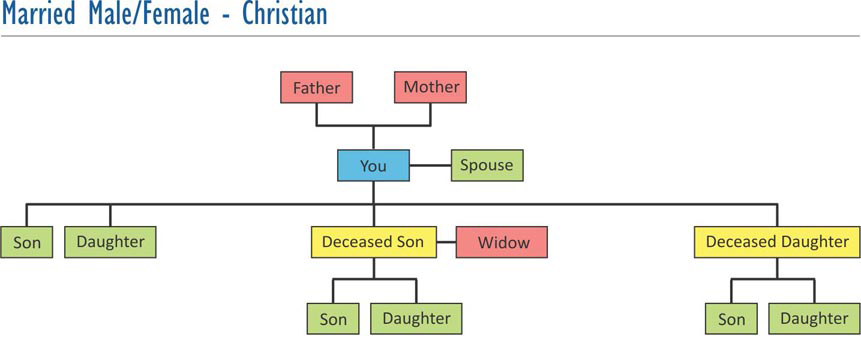

Christians in India are governed by Part VI of the Indian Succession Act, 1925[1]. The succession rules differ based on whether the deceased left lineal descendants. When a Christian dies intestate leaving lineal descendants, the widow receives one-third of the property, with the remaining two-thirds divided equally among the children. Sons and daughters inherit equal shares, reflecting the relatively egalitarian approach of Christian personal law in India.

If a Christian dies leaving a widow but no lineal descendants or father, the widow inherits half the property. The other half is distributed among the deceased’s kindred, following a specific order of preference. In cases where there are lineal descendants but no widow, the children divide the entire estate equally. These provisions demonstrate the Act’s attempt to balance spousal protection with recognition of broader family ties.

Muslim Succession: Islamic Law Principles

Muslim intestate succession in India follows principles derived from Islamic law, specifically Quranic injunctions regarding inheritance shares. Unlike other communities, Muslims are not governed by a comprehensive codified statute but rather by traditional Islamic jurisprudence applied through judicial decisions and scholarly interpretations.

Under Sunni law, which most Indian Muslims follow, specific fractional shares are allocated to different relatives. The widow receives one-eighth of the estate if there are children and one-fourth if there are no children. Daughters receive half the share of sons, a provision that remains contentious in contemporary debates about gender equality. The Quran specifies these shares precisely, and deviation from them is generally not permitted under classical Islamic law.

Shia law, followed by a minority of Indian Muslims, has somewhat different provisions, particularly regarding daughters and certain other relatives. The fundamental difference lies in the recognition of certain heirs and the calculation of shares, though the basic framework of predetermined fractional distribution remains similar.

The Importance of Testamentary Succession

While intestate succession laws provide a safety net, they come with significant limitations that make will-making advisable for most individuals. Intestate succession follows rigid statutory schemes that may not reflect personal preferences, family dynamics, or specific circumstances. A person might wish to provide more generously for a disabled child, recognize a non-traditional family arrangement, or support charitable causes, none of which is possible under intestate succession.

Creating a will allows individuals to exercise autonomy over their property distribution, ensuring that assets reach intended beneficiaries in desired proportions. It can prevent family disputes by clearly articulating the deceased’s wishes, reducing ambiguity and potential litigation. Wills can also include guardianship provisions for minor children, a crucial consideration that intestate succession laws do not address.

The process of will-making need not be complicated. While legal assistance is advisable to ensure validity and prevent future challenges, the basic requirements include testamentary capacity, voluntary execution, and proper attestation by witnesses. The Indian Succession Act specifies formal requirements for executing valid wills, and compliance with these provisions helps ensure that one’s testamentary wishes are honored.

Succession and Property Rights: Recent Developments

Indian succession law has evolved considerably in recent decades, largely driven by constitutional values of equality and non-discrimination. The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005, represents a watershed moment in gender-equal inheritance rights, removing explicit discrimination against daughters that had existed in the original 1956 Act.

Judicial pronouncements have further advanced these reforms. Beyond the landmark Vineeta Sharma judgment[3], courts have interpreted succession laws progressively to protect vulnerable family members and recognize changing social realities. The Kerala High Court in Vijaya Kumari v. Sajitha[4] emphasized that succession laws must be interpreted in light of constitutional principles, particularly the equality guarantee under Article 14.

However, challenges remain. Muslim personal law continues to prescribe unequal shares for male and female heirs, a provision that periodically generates debate about the need for reform. Activists and legal scholars argue for either uniform civil code implementation or at least modification of discriminatory provisions within existing personal laws, while others emphasize religious freedom and community autonomy in personal matters.

Practical Implications and Estate Planning

Understanding intestate succession becomes practically significant during estate administration following a death. Legal heirs must obtain succession certificates or letters of administration to claim the deceased’s assets from banks, financial institutions, and other holders. This process involves court proceedings that can be time-consuming and expensive, particularly when disputes arise among potential heirs.

The absence of a will often leads to prolonged litigation as family members contest their entitlements or challenge the application of succession laws. These disputes not only drain financial resources but also create emotional distress during an already difficult period of bereavement. Property remains locked in legal proceedings, unable to be utilized productively or provide support to dependents.

Estate planning through will-making avoids many of these complications. A properly executed will can be probated relatively smoothly, allowing quicker distribution of assets to beneficiaries. It provides clarity and reduces the scope for disputes, though it does not eliminate the possibility of will contests by dissatisfied family members.

Domicile Considerations in Succession

While religion primarily determines which succession law applies, domicile also plays a significant role, particularly for individuals who have connections with multiple jurisdictions. Domicile refers to the place where a person has their permanent home and to which they intend to return. For succession purposes, the law of the deceased’s domicile typically governs the distribution of movable property, while immovable property is governed by the law of the place where it is situated.

This principle can create complexity for Indians living abroad or foreign nationals with property in India. Non-resident Indians must consider both Indian succession laws and the laws of their country of residence when planning their estates. International conventions and bilateral treaties sometimes address these conflicts of law, but careful planning remains essential to avoid unintended consequences.

Conclusion

Intestate succession in India operates through a complex web of personal laws that reflect the country’s religious diversity and historical traditions. While these laws ensure that property does not remain ownerless and that family members receive support, they cannot accommodate individual preferences or unique family situations. The rigid statutory schemes often fail to address contemporary family structures, including second marriages, adopted children, or non-traditional relationships.

The progressive evolution of succession laws, particularly regarding gender equality, represents positive change, yet gaps and inequities persist. The ongoing tension between religious autonomy and constitutional equality continues to shape debates about personal law reform. In this context, testamentary succession through proper will-making emerges as the most effective tool for ensuring that one’s assets are distributed according to personal wishes while providing security for loved ones.

References

[1] Indian Succession Act, 1925.

[2] Hindu Succession Act, 1956.

[3] Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma, (2020) 9 SCC 1.

[4] Vijaya Kumari v. Sajitha, 2021 SCC OnLine Ker 743.

Whatsapp

Whatsapp