Village Form No. 7/12: A Complete Understanding

Introduction to Village Form 7/12

The Village Form 7/12, commonly known as Saat Baara Utara in Maharashtra, represents one of the most crucial land record documents in the state’s revenue administration system. This document serves as the backbone of land ownership verification in rural Maharashtra, combining information from two distinct village forms to create a single extract that details both ownership rights and agricultural usage of land parcels. For anyone involved in property transactions, agricultural operations, or land-related legal proceedings in Maharashtra, understanding this document becomes essential.

The 7/12 extract derives its nomenclature from the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code, 1966, specifically combining Village Form VII and Village Form XII [1]. This merger creates a detailed record that traces land ownership, occupancy rights, cultivation patterns, and various encumbrances that may affect a particular piece of land. While the document has evolved significantly with digitization efforts, its fundamental purpose of maintaining accurate land records for revenue collection and property rights verification remains unchanged.

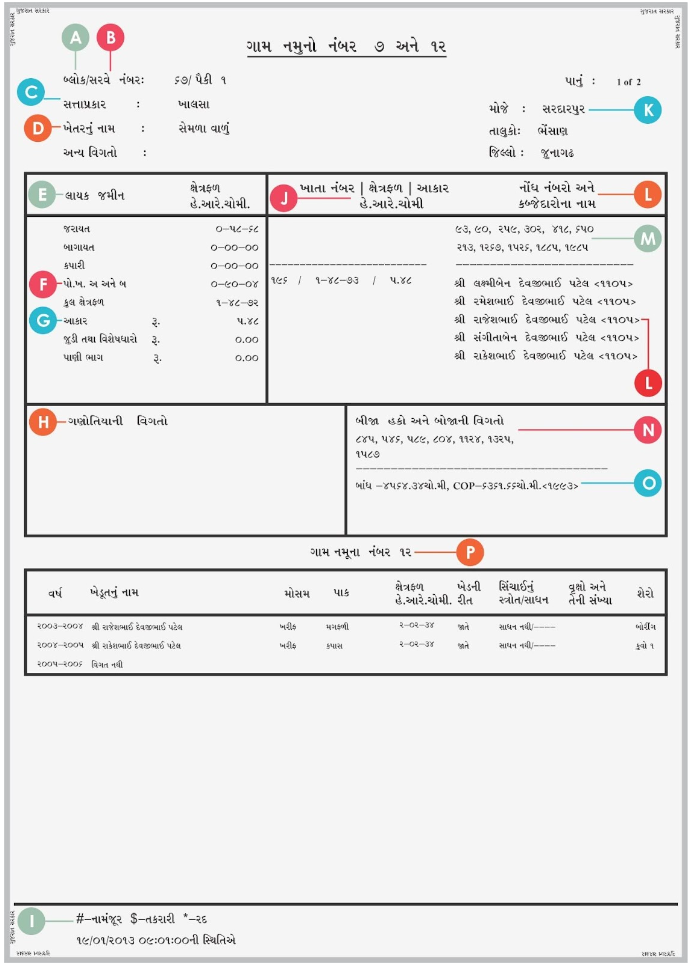

A Typical 7/12 Extract looks like this

Legislative Framework Governing Village Form 7/12

The legal foundation for Village Form 7/12 rests primarily on the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code, 1966 (Mah. XLI of 1966), which came into force on August 15, 1967, replacing various earlier revenue codes that existed in different regions of Maharashtra [2]. This Code established a unified system for land revenue administration across the entire state, though certain provisions do not apply to the City of Bombay. The Code extends to the whole State of Maharashtra but specifically excludes certain chapters from application in Mumbai city, maintaining the distinct character of urban land administration.

The procedural aspects of preparing and maintaining the 7/12 extract are governed by the Maharashtra Land Revenue Record of Rights and Registers (Preparation and Maintenance) Rules, 1971 [3]. These rules prescribe the specific format, contents, and procedures for creating village forms, including the detailed structure of Form VII and Form XII. Rule 3 of these Rules specifies that in areas other than those surveyed under Section 126 of the Code, a record of rights shall be prepared and maintained in the form of a separate card in Form I for each survey number or subdivision of survey number.

The maintenance responsibility falls on the Talathi, who is the primary land record officer at the village level. The Talathi’s duties are defined under the Code and the 1971 Rules, requiring them to maintain accurate mutation entries, collect tax revenue, and update cultivation details regularly. The Circle Inspector exercises supervisory authority, ensuring that village records are maintained in accordance with statutory provisions. This hierarchical structure ensures accountability and accuracy in land record maintenance.

Recent legislative developments include the Maharashtra Land Measurement and Record Keeping Act, 2025, which has introduced provisions for digital signatures and enhanced authentication mechanisms [4]. This new Act aims to streamline the process for citizens seeking official land documentation by introducing digital signatures of Land Revenue Officers, QR codes, and 16-digit verification numbers, eliminating the previous dependency on physical Talathi stamps.

Understanding the Components of Village Form 7/12

Village Form VII constitutes the upper portion of the 7/12 extract and contains critical information about land ownership and occupancy rights. This form includes details such as the survey number, which is the unique identifier assigned to each piece of land within a village during land surveys. The survey numbers may be further divided into sub-divisions when land parcels are split due to inheritance, sales, or other transactions. The form also displays the Gat number, which represents consolidated survey numbers created by the Maharashtra government to simplify land identification.

One of the most important entries in Form VII is the occupancy class designation. The Maharashtra Land Revenue Code recognizes different types of occupancies, with Occupant Class I representing freely transferable lands where owners hold unrestricted rights subject only to payment of land revenue. Section 36(1) of the Code establishes that every occupancy, subject to Section 72 and any lawfully annexed conditions, shall be transferable without any restriction imposed by or under the Code [5]. This provision grants landholders the freedom to alienate their property through sale, gift, mortgage, or any other mode of transfer.

Occupant Class II includes a distinct category of lands that face transfer restrictions. These encompass lands purchased by tenants under the Bombay Tenancy and Agricultural Lands Act, 1948, as well as lands granted by the government to scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, freedom fighters, ex-servicemen, and members of armed forces. Section 36(2) of the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code specifically provides that occupancies held by persons belonging to scheduled tribes cannot be transferred without obtaining permission from the Collector [6]. This protective provision aims to prevent alienation of tribal lands and preserve their economic interests.

The mutation entry, displayed as a circled number in the 7/12 extract, holds particular significance as it reflects the historical changes in ownership or rights over the land. These entries are sourced from Village Form VI, which is the Register of Mutation. Mutations record various types of transfers including sales, gifts, inheritance, mortgages, leases, exchanges, divisions, and court-ordered transfers. However, the legal status of these mutation entries requires careful understanding within the broader framework of property law.

Village Form XII forms the lower portion of the 7/12 extract and documents agricultural characteristics of the land. This section records the types of crops grown, whether the cultivation is irrigated or rain-fed, the area under different crops, details of the cultivator if different from the owner, and the agricultural season. This information serves multiple purposes including assessment of agricultural productivity, verification of land use patterns, and administration of agricultural support schemes.

Legal Interpretation and Limitations of 7/12 Extract

The legal status of the 7/12 extract and its evidentiary value in property disputes has been extensively examined by Indian courts. The Supreme Court has consistently held that revenue records do not constitute documents of title. In the case of Kishore Kumar v. Vittal Patkar (2023), the Supreme Court reiterated the settled legal position that mutation in revenue records neither creates nor extinguishes title, nor does it have any presumptive value on title [7]. The Court emphasized that all a mutation entry does is entitle the person in whose favor it is recorded to pay land revenue for the concerned land.

This principle was elaborated in Prahlad Pradhan v. Smt. Bijoya Kumar Pattnaik (2023), where the Supreme Court observed that revenue entries are maintained for fiscal purposes to determine who is primarily responsible to pay revenue to the Government. The Court stated that revenue entries do not decide title, which can only be decided by civil courts through proper adjudication of title suits. The judgment clarified that while revenue records cannot be direct evidence of legal title, they may nevertheless be used for corroboration purposes when supported by other substantive evidence.

The Court has repeatedly emphasized that in title disputes, the plaintiff cannot succeed by merely pointing out lacunae in the defendant’s title. In Akula Satyanarayana v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2023), the Supreme Court held that having instituted a suit for declaration of title, the burden of proof rests squarely on the plaintiff to reasonably establish the probability of better title [8]. The plaintiff must stand on the strength of their own title rather than relying on weaknesses in the opponent’s case. Revenue documents alone, being fiscal in nature, are insufficient to discharge this burden.

The maxim “nemo dat quod non habet” (no one can confer a better title than what they themselves possess) applies with full force to transactions recorded in revenue records. The Supreme Court has held that a vendor cannot transfer title to a vendee better than what they themselves possess. Therefore, if mutation entries favor a person who never held valid title, subsequent mutations based on transactions with such person will not confer valid title to the transferees.

Despite these limitations, the 7/12 extract serves important practical functions in land administration. It provides prima facie evidence of possession and cultivation, which can be relevant in certain legal proceedings. It helps establish the chain of possession, though not ownership. The document is accepted by banks and financial institutions as supporting documentation for agricultural loans, though lenders typically require additional title verification. Government departments rely on 7/12 extracts for implementing various welfare schemes and subsidies targeted at farmers and landholders.

Mutation Proceedings and Their Legal Significance

The mutation process in Maharashtra follows specific procedures outlined in the 1971 Rules. When any change in ownership or rights occurs, Section 149 of the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code requires that information about transactions affecting land rights must be reported to revenue authorities. The Talathi then makes a pencil entry in the record of rights and issues notices to interested parties under Rule 13 of the 1971 Rules [9]. This notice-based system ensures that all affected parties have an opportunity to raise objections before mutation entries are certified.

After issuing notice, if objections are received, the Talathi records them in the register of disputed cases (Village Form III). The disputes are then decided by a revenue officer not below the rank of Aval Karkun after providing opportunity for hearing to all interested parties. Once disputes are resolved or if no objections are raised within the prescribed period, the certifying officer certifies the mutation entry, which is then recorded in permanent ink in the record of rights.

The Supreme Court has clarified the nature of mutation proceedings in recent judgments. In Tarachandra v. Bhawarlal (2025), the Court held that revenue authorities may effect mutation based on a registered Will, emphasizing that mutation proceedings are summary and administrative in nature. The Court observed that revenue officers do not exercise judicial or quasi-judicial powers to determine title; their role is confined to maintaining updated revenue records for fiscal purposes. The judgment stated that mutation entries do not create, extinguish, or confirm ownership rights, nor do they bar civil suits for title determination.

The administrative character of mutation proceedings means that even certified mutations can be challenged in civil courts. Section 257 of the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code provides for filing revision applications before higher revenue authorities, while civil courts retain jurisdiction to determine questions of title independently of revenue entries. This dual remedy system ensures that fiscal administration through mutation does not prejudice substantive property rights that must be adjudicated by civil courts.

Recent amendments have introduced provisions allowing mutation based on various documents including registered sale deeds, gift deeds, court decrees, succession certificates, and testamentary documents. However, the fundamental principle remains that mutation is purely administrative and does not settle disputed questions of ownership. Where serious disputes exist regarding genuineness of documents, execution formalities, or competing claims, such matters must be resolved by civil courts before mutation can conclusively reflect ownership.

Practical Applications and Verification Procedures

The 7/12 extract finds extensive practical application in various transactions and administrative processes. In property purchases, particularly in rural areas, buyers examine the 7/12 extract to understand the current recorded holder, check for any encumbrances like mortgages noted in the document, verify the survey number and boundaries, and confirm the occupancy class to understand transfer restrictions. While this document alone does not prove ownership, it provides essential preliminary information about the property’s status in revenue records.

Banks and financial institutions require 7/12 extracts when processing agricultural loan applications. The document helps verify that the applicant is the recorded holder entitled to pay land revenue, check the extent of land being offered as security, examine crop patterns and irrigation status for assessing agricultural viability, and identify any existing loans or mortgages recorded in revenue documents. However, prudent lending institutions conduct additional title verification through legal opinion before sanctioning substantial loans.

Government welfare schemes and agricultural subsidies often require submission of 7/12 extracts to establish eligibility. Schemes providing seeds, fertilizers, irrigation subsidies, or crop insurance use these documents to verify that applicants are actual cultivators or landholders. The cultivation details in Form XII help determine eligibility for crop-specific support programs. However, the Maharashtra government has increasingly moved toward digital verification systems that directly access land records databases rather than requiring paper submissions.

The digitization initiative through the Mahabhulekh portal has transformed access to 7/12 extracts. Citizens can now view these records online by selecting district, taluka, and village, then searching by survey number or owner name. The online system displays 7/12 extracts along with Village Form VIII-A and mutation registers. However, for legal and official purposes, certified copies with digital signatures must be obtained either online through the Aaple Sarkar portal or from the Talathi’s office. The 2025 amendments have made these digitally signed copies legally valid for all purposes, eliminating the need for Talathi’s physical stamp.

Comparative Analysis with Other Land Records

The 7/12 extract should be understood in relation to other land records maintained in Maharashtra. The Village Form VIII-A, also known as the Khatedar register, provides information about land revenue assessment, ownership shares in jointly held properties, and taxation liability. While the 7/12 extract focuses on rights and cultivation, the 8-A record deals specifically with financial obligations and revenue assessment. Both documents together provide a complete picture of land status in revenue administration.

The Property Card, introduced for areas surveyed under Section 126 of the Code, serves a similar function to the 7/12 extract but follows the format prescribed in Rule 7 of the Maharashtra Land Revenue (Village, Town and City Survey) Rules, 1969. These property cards are used primarily in urban and semi-urban areas where city surveys have been conducted. The format differs from traditional 7/12 extracts but contains comparable information about ownership, boundaries, and land use.

Village Form VI, the Mutation Register, complements the 7/12 extract by providing detailed history of all mutations affecting a piece of land. While the 7/12 extract shows only the current certified mutation as a circled entry, the mutation register contains the complete chronological record of all ownership changes. Examining this register helps trace the chain of title and identify any disputed mutations that may affect current ownership status.

Registered sale deeds, gift deeds, and other transfer documents registered under the Registration Act, 1908, hold superior legal status compared to revenue records. Section 17 of the Registration Act mandates registration of documents affecting immovable property worth more than one hundred rupees. The Supreme Court has consistently held that title to immovable property can only be conveyed by registered documents, and unregistered agreements to sell or general powers of attorney cannot transfer ownership. Revenue records may reflect transactions, but they cannot substitute for properly registered transfer documents.

Practical Challenges and Resolution Mechanisms

Discrepancies in 7/12 extracts pose common challenges for landholders and transaction parties. Errors may occur in recording names, survey numbers, land area, or occupancy details. The Maharashtra Land Revenue Code provides mechanisms for correction of such errors through applications to the Talathi, who examines relevant records and documents. If the error is undisputed and clearly established, the Talathi can make corrections subject to supervisory approval. For disputed corrections, formal proceedings with notice to interested parties become necessary.

Disputed mutations require resolution through the dispute settlement mechanism under the 1971 Rules. When objections are raised against proposed mutation entries, the matter is recorded in the register of disputed cases and decided by competent revenue officers after conducting inquiries and providing hearing opportunities. Aggrieved parties can appeal against such decisions to higher revenue authorities under Section 247 of the Code, with the appeal hierarchy extending up to the Maharashtra Revenue Tribunal established under the Code.

The Maharashtra Revenue Tribunal was revived through the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code (Second Amendment) Act, 2007, which transferred all pending cases from Divisional Commissioners to the Tribunal. The Tribunal exercises powers of appeal and revision in revenue matters, providing a specialized forum for resolution of land revenue disputes. However, the Tribunal’s jurisdiction is limited to revenue matters, and it cannot adjudicate questions of title which remain within the exclusive domain of civil courts.

Encroachments and unauthorized occupations present another category of challenges. Section 53 of the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code empowers revenue authorities to take action against unauthorized occupation of government land or land occupied in violation of legal provisions. However, such proceedings are administrative in nature and do not finally determine ownership rights. Persons claiming rights in encroached land must establish their title through civil suits rather than relying on revenue proceedings.

Recent Developments and Digital Initiatives

The Maharashtra government’s digitization drive has significantly modernized land records administration. The Mahabhulekh portal provides online access to 7/12 extracts, 8-A records, and mutation registers across the state. This initiative has reduced the time and effort required to obtain land records, eliminated the need for physical visits to government offices for preliminary verification, and increased transparency in land records maintenance. Citizens can now access these records from anywhere with internet connectivity.

The implementation of the Maharashtra Land Measurement and Record Keeping Act, 2025, marks a significant milestone in land records digitization. The Act provides for digital signatures by Land Revenue Officers on official land documents, authentication through QR codes and 16-digit verification numbers, and legal validity of digitally signed documents for all official purposes. Under the new system, citizens can obtain certified 7/12 extracts for a nominal fee of fifteen rupees, with the digital extract carrying full legal validity without requiring physical Talathi stamps.

The integration of revenue records with the sub-registrar’s office represents another important development. Online mutation systems initiated in 2012 aimed to create connectivity between registration offices and revenue departments, enabling automatic updating of revenue records when property transactions are registered. While implementation has faced challenges, the system continues to evolve toward seamless integration of registration and mutation processes, potentially reducing delays and discrepancies.

Looking forward, the government’s vision includes comprehensive digitization of all land records, integration with geographic information systems for accurate spatial data, blockchain-based record keeping for enhanced security and transparency, and artificial intelligence tools for detecting discrepancies and preventing fraudulent entries. These technological advancements aim to transform land records administration while maintaining the fundamental legal framework established under the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code.

Conclusion

Village Form 7/12 remains an essential component of Maharashtra’s land revenue administration despite its limitations as a title document. Understanding that these records serve primarily fiscal purposes rather than proving ownership is crucial for all stakeholders. The extract provides valuable information about recorded holders, cultivation patterns, and revenue obligations, but cannot substitute for properly registered title documents in establishing ownership rights.

The legislative framework under the Maharashtra Land Revenue Code, 1966, and the Rules made thereunder provides a structured system for maintaining land records. The recent digitization initiatives have enhanced accessibility and authenticity of these records while preserving their administrative character. As technology continues to reshape land administration, the fundamental principles established by statute and judicial interpretation will continue guiding the proper use and interpretation of Village Form 7/12 in property transactions and legal proceedings throughout Maharashtra.

References

[1] Maharashtra Land Revenue Record of Rights and Registers (Preparation and Maintenance) Rules, 1971. Available at: https://www.latestlaws.com/bare-acts/state-acts-rules/maharashtra-state-laws/maharashtra-land-revenue-code-1966/maharashtra-land-revenue-record-of-rights-and-registers-preparation-and-maintenance-rules-1971/

[2] Maharashtra Land Revenue Code, 1966 (Mah. XLI of 1966). Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/15974

[3] Village Form VII Record of Rights (Adhikar Abhilekh Patrak). Available at: https://forestsclearance.nic.in/writereaddata/Addinfo/0_0_31129121612171Catergory5.pdf

[4] Free Press Journal. (2024). Maharashtra Govt Grants Full Legal Validity To Digital 7/12 Extracts. Available at: https://www.freepressjournal.in/mumbai/maharashtra-govt-grants-full-legal-validity-to-digital-712-extracts-other-vital-land-records

[5] Maharashtra Land Revenue Code, 1966, Section 36. Available at: https://bombayhighcourt.nic.in/libweb/acts/1966.41.pdf

[6] India Code. Maharashtra Land Revenue Code, 1966. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15974/5/the_maharashtra_land_revenue_code.pdf

[7] LiveLaw. (2024). Revenue Records Won’t Confer Title: Supreme Court. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/supreme-court-judgment-burden-of-proof-land-title-dispute-kishore-kumar-vs-vittal-patkar-242714

[8] Supreme Court of India. (2023). Akula Satyanarayana v. State of Andhra Pradesh. Available at: https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2011/10304/10304_2011_5_1501_48291_Judgement_20-Nov-2023.pdf

[9] Maharashtra Land Revenue Record of Rights and Registers (Preparation and Maintenance) Rules, 1971, Rule 13. Available at: http://www.landsofmaharashtra.com/rules1971.html

Whatsapp

Whatsapp