Understanding the Criminal Trial Process in India: A Comprehensive Legal Framework

Introduction to India’s Criminal Justice System

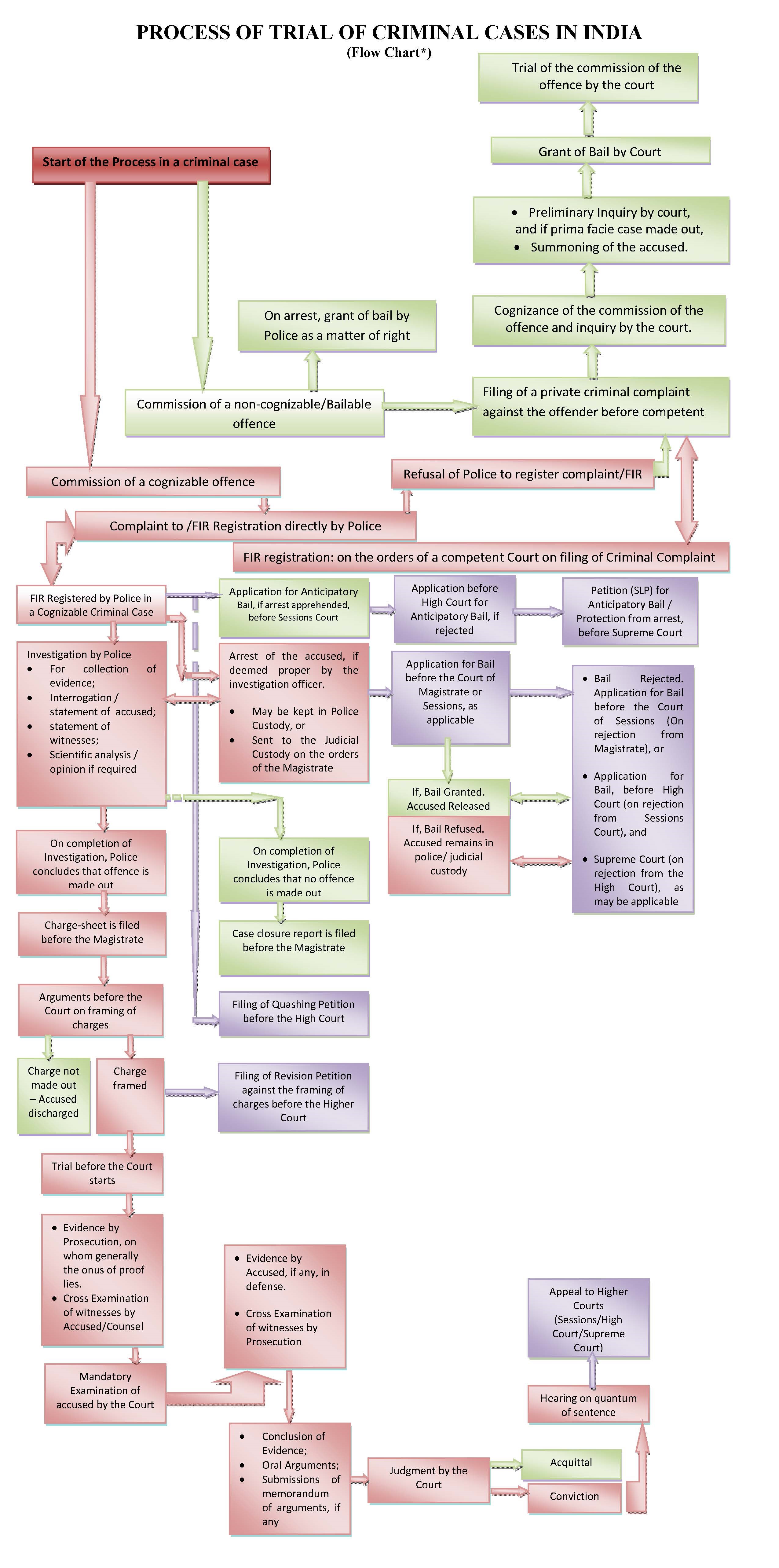

India has developed an elaborate system for administering criminal justice through three principal legislative instruments. The criminal justice architecture in the country rests primarily on the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, which provides the procedural framework for conducting criminal trial Process [1]. This legislation works in conjunction with the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (Act No. 45 of 1860), which defines substantive offences and prescribes punishments, and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, which governs the admissibility and evaluation of evidence in judicial proceedings [2].

The criminal trial process, as outlined in the Code of Criminal Procedure, establishes detailed protocols for investigation, arrest, detention, bail, trial conduct, and the protection of accused persons’ rights. This framework reflects India’s commitment to the adversarial system of justice, in which the prosecution bears the burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, and the accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty. The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that Article 21 of the Constitution of India, which protects the right to life and personal liberty, must be interpreted expansively to safeguard citizens against arbitrary state action and to ensure fair trial procedures guided by principles of natural justice.

The Adversarial System and Burden of Proof

The criminal trial process in India follows the adversarial system, a system inherited from British jurisprudence and refined through post-independence constitutional values. Under this model, the prosecution representing the state must establish the accused’s guilt through credible evidence presented before an impartial tribunal. The standard of proof required in criminal matters is “beyond reasonable doubt,” which is considerably higher than the “preponderance of probabilities” standard used in civil litigation.

This presumption of innocence constitutes a fundamental pillar of criminal jurisprudence recognized in international instruments including the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. The principle places the onus squarely on the investigating agency and prosecution to gather admissible evidence, examine witnesses, and construct a case that satisfies judicial scrutiny. Only in exceptional circumstances involving specific statutes such as anti-terrorism legislation has the legislature imposed a reverse burden on accused persons claiming innocence.

The judiciary has consistently acted as guardian of individual liberty against potential executive overreach. High Courts and the Supreme Court have developed an extensive body of precedent protecting accused persons’ rights while balancing society’s interest in effective law enforcement and crime prevention. This jurisprudence has shaped the interpretation and application of procedural safeguards contained in the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Classification of Offences Under Indian Law

Understanding the criminal trial process requires familiarity with how offences are categorized under Indian law. The First Schedule to the Code of Criminal Procedure provides a classification system that determines the procedures applicable to different offences. This classification operates along two principal dimensions: whether an offence is cognizable or non-cognizable, and whether it is bailable or non-bailable.

Cognizable and Non-Cognizable Offences

Section 2(c) of the Code defines a cognizable offence as one in which a police officer may arrest the accused without a warrant [3]. These typically involve serious crimes where immediate police intervention is necessary to prevent the destruction of evidence or protect public safety. Cognizable offences include murder, rape, theft, robbery, and other grave violations that threaten social order. When a cognizable offence is reported, police are duty-bound to register a First Information Report and commence investigation without requiring prior judicial authorization.

Conversely, Section 2(l) defines a non-cognizable offence as one where police lack authority to arrest without a warrant. These generally involve less serious matters such as defamation, certain assaults, and public nuisances. For non-cognizable offences, police must ordinarily obtain a warrant from a Magistrate before making an arrest. The legislature has drawn this distinction to balance effective law enforcement against the protection of individual liberty from arbitrary detention.

Bailable and Non-Bailable Offences

The Code’s categorization of offences as bailable or non-bailable determines the accused’s entitlement to release pending trial. Under Section 436 of the Code, a person accused of a bailable offence has a statutory right to bail upon arrest, either from the police officer or subsequently from the Magistrate [4]. This right is not discretionary but mandatory, subject only to the accused’s ability to furnish the required bond with or without sureties. Bailable offences typically include those punishable with imprisonment of less than three years or with fine only.

Non-bailable offences, by contrast, do not confer an automatic right to release. Section 437 governs bail applications in such cases, vesting judicial discretion in the Magistrate or Court to determine whether the accused should be released pending trial [5]. The legislature has prescribed that offences punishable with imprisonment of three years or more are generally non-bailable. The distinction reflects legislative judgment about the gravity of different offences and the risk posed by accused persons remaining at liberty during proceedings.

The Second Schedule’s Table II to the Code provides general guidelines for determining an offence’s status when the relevant statute is silent. Offences punishable with imprisonment for less than three years or with fine only are presumptively cognizable and bailable, while those punishable with three years or more imprisonment are cognizable and non-bailable. This default framework ensures consistency across the criminal justice system while allowing specific statutes to prescribe different classifications where warranted.

Initiation of Criminal Proceedings

Criminal proceedings in India may be initiated through multiple pathways depending on the nature of the alleged offence and the circumstances of its commission. The Code provides distinct procedures for cognizable and non-cognizable offences, recognizing the different investigative requirements and urgency associated with various categories of crime. These procedures form the foundation of the criminal trial process in India.

Investigation of Cognizable Offences

Section 156(1) of the Code empowers any police officer to investigate a cognizable offence without requiring orders from a Magistrate [6]. Upon receiving information about the commission of such an offence, the officer in charge of a police station must register a First Information Report documenting the complaint. This FIR marks the commencement of formal criminal investigation and triggers the police’s duty to gather evidence, examine witnesses, and identify suspects.

The investigation process encompasses various powers conferred on police officers including the authority to summon and examine witnesses, conduct searches and seizures upon warrant, and make arrests without warrant in appropriate circumstances. Throughout this process, the Code mandates compliance with procedural safeguards protecting accused persons’ rights, including the requirement that arrested individuals be informed of the grounds for arrest and produced before a Magistrate within twenty-four hours.

Judicial Intervention in Cases of Police Inaction

The framers of the Code recognized that police might sometimes fail to register or properly investigate cognizable offences due to negligence, bias, or external pressure. Section 156(3) provides an important remedy by empowering Magistrates to direct police to register a case and conduct investigation when a complainant demonstrates that police have improperly refused to act [7]. This power serves as a check on police discretion and ensures that complaints of serious offences receive appropriate attention regardless of the complainant’s social or economic status.

Alternatively, aggrieved persons may approach a Magistrate directly under Section 190 of the Code, which authorizes Magistrates to take cognizance of offences based on complaints, police reports, or information from other sources [8]. Upon taking cognizance, the Magistrate may conduct an inquiry personally or direct police to investigate and submit a report. This parallel mechanism prevents police gatekeeping from denying victims access to justice.

Non-Cognizable Offences and Private Complaints

For non-cognizable offences, police lack authority to investigate without Magistrate’s orders. Complainants in such cases must file a criminal complaint directly before the appropriate Magistrate under Section 190 of the Code. The Magistrate then examines whether the complaint discloses sufficient grounds to proceed and may either conduct an inquiry or dismiss the complaint if it appears frivolous or lacking prima facie merit. This procedure ensures judicial oversight of cases involving relatively minor offences where arrest without warrant would be inappropriate.

The Bail Framework Under Indian Law

Bail provisions constitute a critical component of the criminal justice system, balancing society’s interest in ensuring accused persons’ availability for trial against the constitutional imperative to protect personal liberty. Chapter XXXIII of the Code, spanning Sections 436 to 450, establishes a differentiated framework depending on whether the offence is bailable or non-bailable and whether the application is made before or after arrest [9].

Regular Bail for Bailable Offences

Section 436 creates a statutory entitlement to bail for persons accused of bailable offences. This provision recognizes that for less serious crimes, the presumption of innocence and right to liberty outweigh concerns about flight risk or evidence tampering. When a person accused of a bailable offence is arrested, either the police officer at the time of arrest or the Magistrate before whom the accused is produced must release the individual upon execution of a bond with or without sureties. The only discretion permitted concerns whether to require sureties and in what amount, not whether to grant bail itself.

This mandatory character of bail for bailable offences reflects legislative recognition that prolonged pre-trial detention for minor offences inflicts punishment without conviction and violates fundamental fairness. Courts have emphasized that authorities must not use their discretion regarding surety requirements to effectively deny the statutory right to bail by imposing unreasonably onerous conditions.

Discretionary Bail for Non-Bailable Offences

The framework for non-bailable offences operates quite differently, vesting substantial discretion in judicial authorities. Section 437 permits but does not mandate the grant of bail to persons accused of non-bailable offences when they are not charged with offences punishable with death or life imprisonment, or when there appear insufficient grounds for believing the accused has committed such offences. Even when these conditions are satisfied, courts must consider numerous factors including the nature and gravity of the accusation, the character and antecedents of the accused, the likelihood of the accused absconding or interfering with witnesses or evidence, and whether prolonged incarceration would cause undue hardship.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that bail should be the norm and jail the exception even in non-bailable cases, unless specific circumstances justify continued detention. This principle, often summarized as “bail not jail,” reflects constitutional values protecting personal liberty and recognizing that pre-trial detention imposes severe hardship on accused persons who remain legally innocent. Nevertheless, courts must also weigh public safety concerns and the risk that release may enable further offending or obstruction of justice.

Anticipatory Bail: A Unique Indian Innovation

Section 438 of the Code introduces the concept of anticipatory bail, a distinctive feature of Indian criminal procedure that allows persons apprehending arrest to seek protective orders from High Courts or Sessions Courts [5]. This provision enables individuals who reasonably believe they may be arrested for non-bailable offences to obtain directions that, should arrest occur, they must be released on bail immediately. The provision was introduced to protect individuals from harassment through false or politically motivated accusations.

The Sibbia Judgment and Liberal Interpretation

The scope and application of Section 438 received authoritative interpretation from the Supreme Court in the landmark case of Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia v. State of Punjab, decided on April 9, 1980 [9]. In this case, several ministers in the Punjab government facing corruption allegations sought anticipatory bail. The Punjab and Haryana High Court had dismissed their applications while laying down eight restrictive propositions severely limiting the availability of anticipatory bail, including that the power was extraordinary and should be exercised sparingly, that limitations from Section 437 must be read into Section 438, and that anticipatory bail could not be granted for offences punishable with death or life imprisonment.

The Supreme Court, in a judgment authored by Chief Justice Y.V. Chandrachud for a five-judge Constitution Bench, comprehensively rejected these restrictions. The Court held that Section 438 confers wide discretionary power on High Courts and Courts of Session to grant anticipatory bail, and that this discretion should not be curtailed by reading into the statute conditions not placed there by the legislature. The Court emphasized that anticipatory bail serves the important function of protecting individual liberty against wrongful or malicious prosecution while the judicial process determines the truth of allegations.

The Sibbia judgment established several critical principles that continue to guide anticipatory bail jurisprudence. First, the filing of a First Information Report is not a precondition for seeking anticipatory bail; the provision may be invoked based on reasonable apprehension of arrest even before formal charges are filed. Second, courts should not adopt a mechanical approach but must examine each case’s specific facts and circumstances. Third, while granting anticipatory bail, courts may impose conditions including requirements that the accused cooperate with investigation, refrain from tampering with evidence or influencing witnesses, and surrender passport or restrict travel. Fourth, anticipatory bail cannot be granted with blanket protection against all possible accusations but must relate to specific alleged offences.

Balancing Liberty and Investigation

The Supreme Court in Sibbia recognized that anticipatory bail involves balancing two legitimate societal interests: protecting personal liberty and ensuring effective investigation and prosecution of crime. The Court observed that society has a vital stake in both these interests, though their relative weight depends on specific circumstances. In making this balance, courts must consider factors such as the nature and gravity of accusations, the applicant’s antecedents and character, the likelihood of the applicant fleeing from justice, and whether there is reason to believe the accusation is false or motivated by malice.

The judgment emphasized that personal liberty is a fundamental constitutional value that should not be lightly compromised. Pre-arrest detention, even for short periods, can cause humiliation and stigma that persists regardless of eventual acquittal. For individuals of standing in society, the mere fact of arrest may irreparably damage reputation and career prospects. Section 438 was enacted to prevent such unjust consequences when accusations lack foundation or when the accused poses no real threat to the investigative process.

Procedural Rights of Accused Persons

The Code of Criminal Procedure incorporates numerous safeguards protecting the rights of accused persons throughout the investigation and criminal trial process. These protections reflect constitutional values and international human rights standards, ensuring that the state’s coercive power is exercised fairly and in accordance with law.

Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. The Supreme Court has interpreted this provision dynamically to require that such procedures must be just, fair, and reasonable. Any procedural requirement that is arbitrary, oppressive, or violative of natural justice principles will be struck down as unconstitutional even if enacted by a competent legislature.

Accused persons have the right to be informed promptly of the grounds for arrest and the nature of charges against them. They must be produced before a Magistrate within twenty-four hours of arrest, excluding travel time. The Code prohibits police from detaining accused persons for extended periods without judicial authorization, and Magistrates must independently satisfy themselves that continued detention is justified before remanding accused persons to police or judicial custody.

During criminal investigation and trial Process, accused persons enjoy the right against self-incrimination protected by Article 20(3) of the Constitution, which provides that no person accused of an offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself. This right extends not merely to testimonial evidence but to any compelled conduct that may prove incriminating. Police may not subject accused persons to narcoanalysis, polygraph examinations, or brain mapping without their informed consent.

Conclusion

The criminal trial process in India represents a sophisticated attempt to balance multiple imperatives: protecting individual liberty, ensuring effective prosecution of genuine offenders, maintaining public confidence in the justice system, and upholding constitutional values of fairness and due process. The framework established by the Code of Criminal Procedure, interpreted through decades of judicial precedent, provides detailed procedures governing every stage from initial investigation through final appeal.

This Criminal Trial Process architecture reflects India’s commitment to the rule of law and recognition that criminal justice must be administered not merely efficiently but justly. The extensive safeguards protecting accused persons’ rights acknowledge that state power, though necessary for maintaining social order, poses inherent risks of abuse that must be constrained through institutional checks and judicial oversight. The Supreme Court’s robust enforcement of constitutional guarantees has ensured that these procedural protections retain meaningful substance rather than becoming mere formalities.

As India’s criminal justice system continues evolving to address contemporary challenges including organized crime, terrorism, cybercrime, and white-collar offences, the fundamental principles established in the Code of Criminal Procedure remain vital. These principles ensure that the pursuit of security and order never overshadows the protection of human dignity and individual liberty that lie at the heart of constitutional democracy.

References

[1] Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 – India Code. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/16225

[2] Indian Penal Code, 1860 (Act No. 45 of 1860) – India Code. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/12850

[3] Code of Criminal Procedure – Definitions (Section 2) – Devgan.in. Available at: https://devgan.in/crpc/chapter_01.php

[4] Bail Provisions in India – Legal Service India. Available at: https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/legal/article-14917-bail-provisions-in-india-a-comprehensive-guide-to-sections-436-439-of-crpc-1973.html

[5] Bail Provisions in India – Lead India. Available at: https://www.leadindia.law/blog/en/bail-provisions-in-india/

[6] Code of Criminal Procedure (India) – Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Criminal_Procedure_(India)

[7] Understanding the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 – LawCrust. Available at: https://lawcrust.com/criminal-procedure-code-1973/

[8] CrPC: Provisions As To Bail And Bonds – Devgan.in. Available at: https://devgan.in/crpc/chapter_33.php

[9] Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia v. State of Punjab (1980) – iPleaders. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/gurbaksh-singh-sibbia-ors-vs-state-of-punjab/

Whatsapp

Whatsapp