Stages of Criminal Trial in India: A Comprehensive Legal Analysis

Introduction

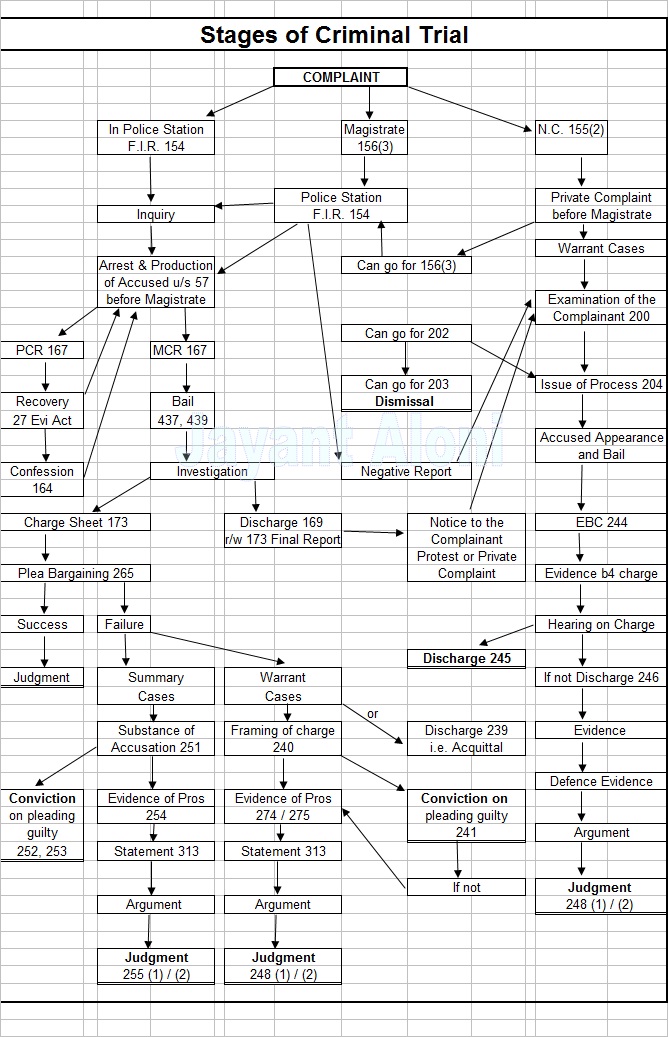

The criminal justice system in India operates through a structured procedural framework that safeguards both the interests of victims seeking justice and the fundamental rights of accused persons. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (hereinafter referred to as CrPC) establishes this comprehensive framework, delineating the various stages of criminal trial through which a case progresses from the moment an offense is reported until the final adjudication. Understanding these stages of criminal trial is essential for legal practitioners, law enforcement officials, and citizens alike, as each phase serves a distinct purpose in the administration of criminal justice. The entire criminal proceeding can be categorically divided into three broad stages: the pre-trial stage, the trial stage, and the post-trial stage. Each stage involves specific procedures, legal safeguards, and judicial oversight mechanisms designed to ensure fairness, transparency, and adherence to the principles of natural justice.

STAGES OF CRIMINAL TRIAL

Pre-Trial Criminal Stages

Registration of First Information Report

The criminal justice process commences with the registration of a First Information Report (FIR) under Section 154 of the CrPC. This provision mandates that when information relating to the commission of a cognizable offense is given orally or in writing to an officer in charge of a police station, such officer shall reduce the information into writing and provide a copy to the informant free of cost. The FIR serves as the foundational document that sets the criminal machinery in motion and provides the initial narrative of the alleged offense. The landmark judgment in Lalita Kumari v. Government of Uttar Pradesh [1] established definitively that registration of an FIR is mandatory when information discloses the commission of a cognizable offense. The Constitution Bench categorically held that the word “shall” in Section 154(1) demonstrates clear legislative intent requiring mandatory registration without preliminary inquiry in most circumstances. The Court observed that if information disclosing a cognizable offense is laid before an officer in charge of a police station satisfying the requirements of Section 154(1), the police officer has no option except to register a case on the basis of such information.

However, the Lalita Kumari judgment also recognized certain exceptional categories of cases where a preliminary inquiry may be conducted before FIR registration. These exceptions include matrimonial disputes, commercial offenses, medical negligence cases, corruption cases, and cases where there is abnormal delay in initiating criminal prosecution. When such preliminary inquiry is warranted, it must be completed within seven days, and the police must record reasons in the General Diary if no cognizable offense is found. For non-cognizable offenses, the procedure differs substantially. Under Section 155 of the CrPC, a Non-Cognizable Report is registered, but the police cannot commence investigation or arrest the accused without obtaining orders from a Magistrate having jurisdiction to try such case. This distinction between cognizable and non-cognizable offenses reflects the legislative balance between expeditious action for serious crimes and judicial oversight for lesser offenses.

Investigation Process

Following FIR registration, the investigation phase begins under the supervision of a police officer empowered under Section 156 of the CrPC. The investigation encompasses collection of evidence, examination of witnesses, forensic analysis, and interrogation of suspects. During this critical phase, investigating officers must meticulously gather and preserve evidence while respecting the legal rights of all parties involved. The investigation culminates in the submission of a charge sheet under Section 173 of the CrPC, which contains the complete investigation report along with all relevant documents and evidence. The charge sheet represents the prosecution’s formal accusation and forms the basis for subsequent judicial proceedings. If the investigation reveals insufficient evidence to proceed, the police may submit a final report recommending closure of the case, though such closure remains subject to judicial scrutiny and the Magistrate retains power to take cognizance despite the closure report.

Cognizance and Process Issuance

After submission of the charge sheet, the Magistrate examines the documents under Section 190 of the CrPC to determine whether to take cognizance of the offense. Taking cognizance is a judicial function that involves application of judicial mind to the suspected commission of an offense, though it does not necessarily involve any formal action. If the Magistrate is satisfied that sufficient grounds exist for proceeding against the accused, process is issued under Section 204 of the CrPC requiring the accused to appear before the court. This stage serves as an initial judicial filter ensuring that only cases with sufficient prima facie evidence proceed to trial, thereby protecting individuals from frivolous or malicious prosecutions.

Trial Stage

Framing of Charges

In cases exclusively triable by the Court of Session, after considering the record of the case and hearing both parties, the Judge must frame charges under Section 228 of the CrPC if there are grounds for presuming that the accused has committed the offense. Conversely, under Section 227 of the CrPC, if upon consideration of the record and documents submitted therewith, and after hearing submissions of both prosecution and defense, the Judge considers that there is not sufficient ground for proceeding against the accused, he shall discharge the accused and record reasons for such discharge. The scope and application of Section 227 has been extensively examined by courts. In State of Orissa v. Debendra Nath Padhi [2], a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court held that Section 227 was incorporated specifically to save the accused from prolonged harassment which is a necessary concomitant of protracted criminal trial. The Court clarified that at the stage of framing charges, no provision in the Code grants the accused any right to file material or documents in his favor, and the Court must confine its examination to the record of the case as submitted by the prosecution along with the charge sheet. This landmark judgment established that defense material cannot be advanced at the stage of discharge since the defense of the accused is irrelevant at that preliminary stage. The standard for discharge under Section 227 requires judicial evaluation of whether prosecution materials, taken at face value, disclose sufficient grounds for trial, without entering into detailed assessment of evidence which is the domain of the trial proper.

Recording of Evidence

Once charges are framed, the prosecution presents its evidence before the court. This stage involves examination-in-chief of prosecution witnesses, cross-examination by the defense, and re-examination if necessary. Both oral testimony and documentary evidence are presented during this crucial phase. The prosecution bears the burden of proving the accused’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt, consistent with the fundamental presumption of innocence that pervades criminal jurisprudence. The adversarial system followed in India places the onus squarely on the prosecution to establish its case, and the accused is under no obligation to prove innocence.

Examination of Accused

After conclusion of prosecution evidence, Section 313 of the CrPC mandates examination of the accused for the purpose of enabling him to personally explain any circumstances appearing in the evidence against him. This provision embodies the fundamental principle of fairness and natural justice, ensuring that the accused has an opportunity to respond to incriminating circumstances. Under Section 313(1)(b), the court shall, after witnesses for prosecution have been examined and before the accused is called upon for his defense, question him generally on the case. Importantly, Section 313(2) provides that no oath shall be administered to the accused when examined under this provision, and Section 313(3) clarifies that the accused shall not render himself liable to punishment by refusing to answer questions or by giving false answers. The answers given by the accused may be taken into consideration in the inquiry or trial and put in evidence for or against him. The examination under Section 313 is not a mere procedural formality but serves vital functions in the criminal trial process. It provides the accused an opportunity to explain incriminating circumstances, helps the court in appreciating the entire evidence adduced during trial, and ensures compliance with principles of natural justice. The proper methodology requires inviting the attention of the accused to specific circumstances and evidence, with questions being clear, specific, and comprehensible to the accused. Circumstances not put to the accused under Section 313 cannot be used against him and must be excluded from consideration.

Defense Evidence

Following examination under Section 313, the accused has the opportunity to present defense evidence. The accused may produce witnesses, documentary evidence, and any other material to disprove the prosecution’s allegations or establish any defense available in law. This stage is crucial as it allows the accused to rebut the prosecution’s case and present an alternative narrative. The general principle that the accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty means that even if the prosecution has presented a strong case, the accused retains the right to present evidence that may cast doubt on the prosecution’s version.

Final Arguments and Judgment

After completion of evidence from both sides, the prosecution and defense present their final arguments before the court. During this stage, both parties summarize the evidence, highlight key points supporting their respective positions, and present legal arguments on the applicability of various provisions of substantive and procedural law. The court then reserves the matter for judgment, during which the presiding officer carefully examines all evidence, assesses witness credibility, applies relevant legal principles, and arrives at a conclusion regarding the accused’s guilt or innocence. The judgment must be reasoned, clear, and based on proper appreciation of evidence. If the accused is found guilty, the court proceeds to the sentencing stage, considering various factors including the severity of the offense, the accused’s criminal record, and any aggravating or mitigating circumstances. In cases involving capital punishment, the “rarest of rare” doctrine established in Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab [3] governs the imposition of death penalty. The Supreme Court in Bachan Singh held that the death penalty should be imposed only in the rarest of rare cases when the alternative option of life imprisonment is unquestionably foreclosed. This doctrine requires judges to balance aggravating and mitigating circumstances while determining whether death sentence is appropriate punishment, ensuring that capital punishment remains an exception rather than the rule. The Court emphasized that special reasons must be provided under Section 354(3) of the CrPC when imposing death penalty, and these reasons must reflect consideration of both the crime and the criminal.

Post-Trial Stage

Appeals and Revisions

The post-trial stage provides mechanisms for reviewing trial court decisions. An accused convicted by a trial court has the statutory right to appeal against both conviction and sentence to the higher court. The appellate court possesses wide powers to examine the entire case afresh, reassess evidence, and determine whether the trial court’s findings are sustainable. In cases where an appeal is not available or appropriate, the remedy of revision may be invoked under Sections 397 and 401 of the CrPC, though revisional jurisdiction is more limited in scope compared to appellate powers. The availability of these remedies ensures that errors committed by trial courts can be corrected and justice is ultimately served.

Sentence Execution

If no appeal is filed or the appellate court upholds the conviction and sentence, the judgment becomes final and executable. The sentence execution stage involves implementation of the punishment imposed by the court, whether it be imprisonment, fine, or in exceptional cases, capital punishment. The execution of sentences is governed by specific provisions in the CrPC and relevant prison manuals, ensuring that even at this final stage, the rights and dignity of the convicted person are respected to the extent compatible with the punishment imposed.

Regulatory Framework and Safeguards

The entire stages of criminal trial is regulated by an intricate framework of procedural laws designed to balance competing interests. The CrPC contains numerous safeguards protecting the rights of the accused, including provisions relating to bail, time limits for completion of investigation and trial, legal aid for indigent accused, and protection against arbitrary arrest and detention. Simultaneously, the procedural framework ensures that victims’ rights are protected and the broader interests of society in maintaining law and order are vindicated. The principle of fair trial permeates every stage of criminal proceedings. Fair trial encompasses several elements including equality before the court, access to legal representation, presumption of innocence, opportunity to present defense, examination of prosecution witnesses, right to appeal, and trial by an impartial tribunal. Courts have consistently emphasized that fair trial is not merely procedural formality but a fundamental right integral to the constitutional guarantee under Article 21 of the Constitution.

Conclusion

The stages of criminal trial in India represent a carefully calibrated system designed to serve multiple objectives simultaneously. The procedural framework ensures that genuine offenses are investigated and prosecuted effectively, innocent persons are protected from wrongful conviction, the rights of accused persons are safeguarded throughout proceedings, and public confidence in the criminal justice system is maintained. Each stage from FIR registration to final appeal serves a specific purpose and contains built-in checks and balances preventing abuse of process. The landmark judgments examined in this article demonstrate how Indian courts have interpreted and applied these procedural provisions to evolve a jurisprudence that balances law enforcement imperatives with constitutional values. As the criminal justice system continues to evolve, these foundational principles and procedures remain essential to ensuring that justice is not only done but also seen to be done in every case.

References

[1] Lalita Kumari v. Government of Uttar Pradesh & Ors., (2014) 2 SCC 1, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/10239019/

[2] State of Orissa v. Debendra Nath Padhi, (2005) 1 SCC 568, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/7496/

[3] Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab, (1980) 2 SCC 684, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1235094/#:~:text=Bachan%20Singh%2C%20appellant%20in%20Criminal,sentence%20and%20dismissed%20his%20appeal.

[4] Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973

[5] Drishti Judiciary – Trial Procedure, https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/to-the-point/bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhita-&-code-of-criminal-procedure/trial-procedure

[6] LawCTopus – Stages of Criminal Proceeding in India, https://www.lawctopus.com/clatalogue/clat-pg/stages-of-criminal-proceeding-crpc/

[7] Legal Service India – Procedures Involved in a Criminal Case, https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-5576-procedures-involved-in-a-criminal-case.html

[8] Indian Kanoon – Section 227 CrPC Judgments, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=section+227+doctypes:judgments

[9] iPleaders – Scope and Significance of Examination of Accused under Section 313, https://blog.ipleaders.in/scope-and-significance-of-examination-of-accused-under-section-313-crpc/

Whatsapp

Whatsapp