Summons, Warrant and Sessions Cases in Indian Criminal Law

Introduction

The Indian criminal justice system operates through a well-structured procedural framework established under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC). This framework categorizes criminal cases into distinct types based on the severity of offenses and prescribes specific trial procedures for each category. The three primary classifications that form the backbone of criminal trials in India are summons cases, warrant cases, and sessions trials. Understanding these classifications is crucial for legal practitioners, accused persons, and anyone seeking to comprehend how criminal justice is administered in India.

The classification system serves multiple purposes within the criminal justice framework, distinguishing between Summons, Warrant, and Sessions Cases. It ensures that minor offenses in Summons Cases receive expeditious disposal through simplified procedures, while more serious offenses in Warrant and Sessions Cases undergo rigorous scrutiny through elaborate trial mechanisms. This tiered approach balances the need for swift justice with the requirement of thorough examination in grave matters. The distinction between these case types affects everything from the manner of securing the accused’s presence in court to the length and complexity of the trial procedure itself.

Summons Cases: Definition and Legal Framework

Statutory Definition and Scope

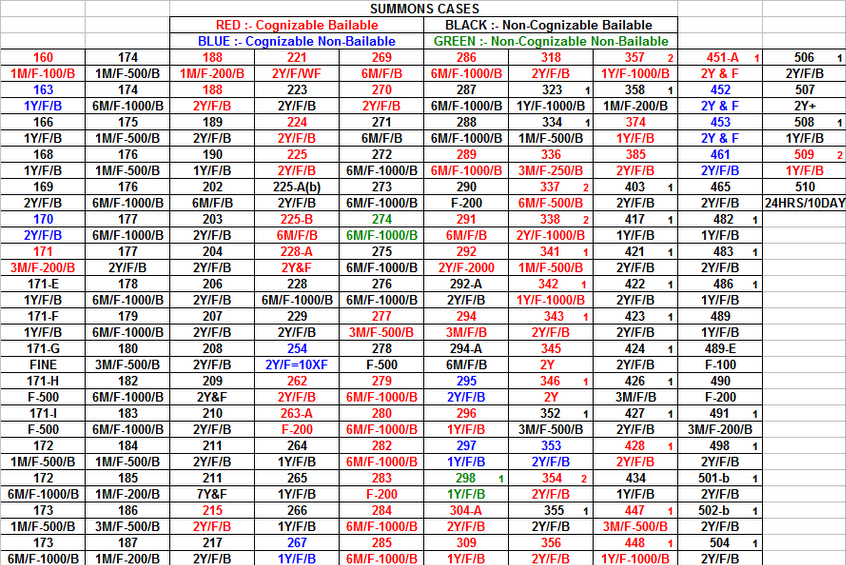

Summons cases represent the least serious category of criminal offenses under the CrPC. According to Section 2(w) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, a summons case is defined as “a case relating to an offence, and not being a warrant-case” [1]. This definition operates through exclusion, meaning any offense that does not fall within the warrant case category automatically becomes a summons case. The legislative intent behind this classification was to create a streamlined procedure for offenses of a less serious nature.

The scope of summons cases encompasses offenses punishable with imprisonment for a term of two years or less, or with fine only, or with both such imprisonment and fine. These are typically minor offenses that do not pose a grave threat to society or individuals. Common examples include simple hurt under Section 323 of the Indian Penal Code, criminal trespass under Section 447, defamation under Section 500, and various offenses under special and local laws that carry lesser punishments.

Procedural Aspects of Summons Cases

The trial procedure for summons cases is governed by Chapter XX of the CrPC, specifically Sections 251 to 259. The procedure is notably simpler and more expeditious compared to warrant cases. When a Magistrate takes cognizance of a summons case, the accused is not arrested but merely summoned to appear before the court. A summons is a written order issued by the court directing a person to appear before it at a specified date and time. This reflects the legislative recognition that accused persons in minor offense cases need not be subjected to the rigors of arrest and detention.

Under Section 251 of the CrPC, when the accused appears or is brought before the Magistrate, the particulars of the offense of which he is accused shall be stated to him. The Magistrate is required to ask the accused whether he pleads guilty or has any defense to make. If the accused pleads guilty, the Magistrate may convict him accordingly. However, if the accused refuses to plead or claims to be tried or makes a defense, the Magistrate must proceed to hear the prosecution and take all such evidence as may be produced in support of the prosecution [2].

The examination of witnesses in summons cases follows a less formal structure. The Magistrate has the discretion to proceed with the case even in the absence of the accused if the offense charged may be lawfully tried in his absence. Section 252 permits the Magistrate to dispense with the personal attendance of the accused and permit him to appear through a pleader if the offense is punishable with fine only or with imprisonment for a term not exceeding one year. This provision acknowledges the minor nature of such offenses and reduces the burden on accused persons.

Recording of Evidence and Judgment

In summons cases, the Magistrate is not required to record the evidence of witnesses in full. Section 258 of the CrPC provides that in summons cases, the Magistrate shall make a memorandum of the substance of the evidence of each witness as the examination proceeds. This is a significant departure from the detailed recording required in warrant cases. The memorandum must be signed by the Magistrate and form part of the record. This abbreviated form of evidence recording expedites the trial process while maintaining a sufficient record for any future reference or appeal.

Upon conclusion of the trial, the Magistrate must deliver judgment in accordance with Section 353 or Section 354 of the CrPC, either convicting or acquitting the accused. The judgment must contain the points for determination, the decision thereon, and the reasons for the decision. Even in summons cases, the requirement of a reasoned judgment ensures judicial accountability and provides a basis for any appellate review that may follow.

Warrant Cases: Nature and Trial Procedure

Definition and Classification

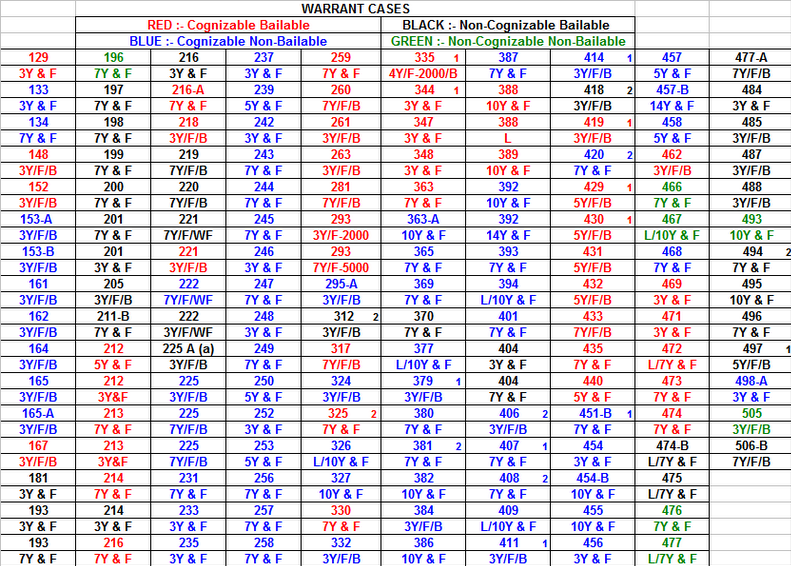

Warrant cases constitute a more serious category of criminal offenses compared to summons cases. Section 2(x) of the CrPC defines a warrant case as “a case relating to an offence punishable with death, imprisonment for life or imprisonment for a term exceeding two years” [3]. This definition encompasses a broad spectrum of serious crimes including murder, grievous hurt, robbery, theft of significant value, cheating involving substantial amounts, and numerous other grave offenses against person and property.

The classification as a warrant case has profound implications for the trial procedure. It signifies that the offense is of such gravity that the legislature has mandated a more elaborate and careful trial procedure. The designation as a warrant case also affects the manner in which the accused’s presence is secured. Unlike summons cases where a mere summons suffices, warrant cases typically require the issuance of a warrant of arrest to ensure the accused’s appearance before the court.

Trial Procedure in Warrant Cases

The procedure for trial of warrant cases by Magistrates is laid down in Chapter XIX of the CrPC, spanning Sections 238 to 250. The trial procedure differs based on whether the case is instituted on a police report or otherwise. Section 238 of the CrPC mandates that warrant cases instituted on police reports shall be tried in accordance with the procedure specified in Sections 238 to 243, while warrant cases instituted otherwise than on police reports shall follow the procedure outlined in Sections 244 to 247.

When a warrant case is instituted on a police report and the accused appears or is brought before the Magistrate, the Magistrate must satisfy himself that documents referred to in Section 173 have been furnished to the accused. These include the police report, the First Information Report, statements of witnesses recorded under Section 161, confessions and statements recorded under Section 164, and any other documents or relevant extracts. This ensures that the accused is aware of the evidence against him before the trial commences.

Discharge and Framing of Charges

One of the most significant features of warrant case procedure is the bifurcated nature of the trial, involving distinct stages of consideration of discharge and framing of charges. Under Section 239, the Magistrate must consider the police report and documents submitted therewith, hear the submissions of the accused and the prosecution, and if he finds that no case against the accused has been made out which would warrant his conviction, he shall discharge the accused. The power to discharge at this preliminary stage serves as a filter to prevent baseless prosecutions from proceeding to full trial [4].

If the Magistrate is of opinion that there is ground for presuming that the accused has committed an offense triable under Chapter XIX, he shall frame in writing a charge against the accused as per Section 240 of the CrPC. The charge must contain particulars as to the time and place of the alleged offense and the person, if any, against whom or the thing, if any, in respect of which it was committed. The charge must be read and explained to the accused, and he shall be asked whether he pleads guilty or claims to be tried. This formal framing of charges marks the commencement of the actual trial.

Evidence and Cross-Examination

After charges are framed and the accused pleads not guilty, the trial proceeds with the prosecution presenting its evidence. Section 243 requires the Magistrate to take all evidence produced in support of the prosecution. Witnesses are examined orally in open court, and their examination-in-chief, cross-examination, and re-examination are recorded. The accused or his pleader has the right to cross-examine prosecution witnesses, which is a fundamental aspect of the right to fair trial.

Upon closure of prosecution evidence, Section 232 empowers the Magistrate to acquit the accused if he considers that no case against the accused has been made out that warrants conviction. This is known as acquittal at the stage of Section 232. If the Magistrate does not acquit at this stage, he must call upon the accused to enter his defense. The accused may then produce his witnesses and evidence. Section 233 mandates that the Magistrate shall record the evidence of witnesses produced by the accused.

Sessions Trials: Jurisdiction and Procedure

Constitutional and Statutory Framework

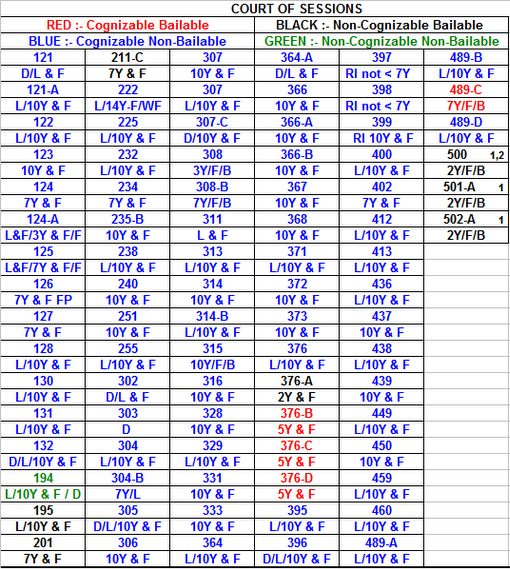

Sessions trials represent the highest tier in the hierarchy of criminal trial procedures. The Court of Session derives its jurisdiction from both constitutional and statutory provisions. Article 233 of the Constitution of India provides for the appointment of District Judges, while the CrPC elaborates their powers and jurisdiction. Section 26 of the CrPC specifically states that subject to other provisions of the Code and any other law, a Court of Session may try any offense [5].

The Sessions Court’s jurisdiction is both territorial and subject-matter based. Territorially, a Sessions Judge presides over a sessions division, which may comprise one or more districts. From a subject-matter perspective, Sessions Courts have exclusive jurisdiction over offenses punishable with imprisonment exceeding seven years, life imprisonment, or death. Section 28 of the CrPC clarifies that when any offense is punishable with imprisonment which may extend to seven years, or with a less severe punishment, a Court of Session may pass any sentence authorized by law for such offense.

Commitment Proceedings

An essential prerequisite for sessions trial is the commitment of the case by a Magistrate. Sessions Courts do not take direct cognizance of offenses except in limited circumstances specified under Section 193 read with Section 199 of the CrPC. The normal route for a case to reach the Sessions Court is through commitment proceedings initiated by a Magistrate. When a Magistrate finds that an offense is exclusively triable by the Court of Session, he must commit the case to the Sessions Court under Section 209 of the CrPC [6].

Section 209 requires the Magistrate to commit the case when it appears to him that the offense is exclusively triable by the Court of Session. Upon commitment, the Magistrate must forward to the Sessions Court the record of the case and the documents and articles, if any, which are to be produced in evidence. The accused must also be sent to the Sessions Court either in custody or on bail. This commitment procedure ensures that the Sessions Judge receives a complete dossier of the investigation and preliminary proceedings.

Trial Procedure Before Sessions Court

The procedure for trial before a Court of Session is governed by Chapter XVIII of the CrPC, comprising Sections 225 to 237. Section 225 mandates that in every trial before a Court of Session, the prosecution shall be conducted by a Public Prosecutor. This requirement underscores the serious nature of offenses tried by Sessions Courts and ensures that the State’s case is presented by a legally qualified professional.

When the accused appears or is brought before the Court of Session pursuant to commitment, the Public Prosecutor opens his case by describing the charge brought against the accused and stating by what evidence he proposes to prove the guilt of the accused as per Section 226. This opening statement provides both the court and the accused with an overview of the prosecution case. Following this, if the accused wishes to make any statement or put in any written statement, he may do so.

Discharge and Framing of Charges in Sessions Trials

Section 227 of the CrPC empowers the Sessions Judge to discharge the accused if, upon consideration of the record of the case and documents submitted with it and after hearing the submissions of the accused and the prosecution, the Judge considers that there is no sufficient ground for proceeding against the accused. The discharge at this stage operates as a bar to further prosecution for the same offense unless the Sessions Judge specifically permits continuation.

If the Judge is satisfied that there is ground for presuming that the accused has committed an offense which is triable under Chapter XVIII, he shall frame in writing a charge against the accused under Section 228 of the CrPC. The charge must be specific, stating clearly the offense with which the accused is charged. Section 228 requires that the charge be read and explained to the accused, and he shall be asked whether he pleads guilty or claims to be tried. The accused’s plea is recorded, and if he pleads guilty, the Judge may convict him accordingly. If the accused refuses to plead or claims trial, the Judge proceeds with the trial.

Evidence Recording and Judgment in Sessions Court

The recording of evidence in Sessions Court follows a meticulous procedure designed to ensure accuracy and fairness. Section 273 of the CrPC mandates that all evidence must be taken in the presence of the accused or his pleader. This ensures the accused’s right to confrontation and cross-examination. Section 274 requires that evidence of each witness must be taken down in writing by the presiding officer in the form of a narrative. The recording must be in the language of the court or in English, and must be shown or read to the witness who may require corrections to be made.

The examination of witnesses proceeds through examination-in-chief, cross-examination, and re-examination. The prosecution presents its witnesses first, and the defense has the right to cross-examine each prosecution witness. This adversarial process allows both sides to test the veracity and reliability of testimony. After the prosecution evidence concludes, Section 230 empowers the Sessions Judge to acquit the accused if he considers that no case has been made out against the accused that warrants conviction.

If the case proceeds beyond this stage, the accused is called upon to enter his defense. Section 233 governs the production of defense evidence. The accused may examine himself as a witness in his defense and may call other witnesses. The procedure for examination of defense witnesses mirrors that of prosecution witnesses. Upon conclusion of all evidence, both prosecution and defense are allowed to address the court with their final arguments. The Sessions Judge then pronounces judgment, which must contain the points for determination, the decision thereon, the reasons for the decision, and the sentence if any.

Comparative Analysis of the Summons, Warrant and Sessions Cases

Procedural Distinctions

Criminal trials in India differ significantly depending on whether the matter is a summons case, a warrant case, or a sessions trial. Summons cases follow the most abbreviated procedure, designed for quick disposal. The absence of formal charge-framing, the permission for trial in absentia in certain situations, and the summary recording of evidence all contribute to expeditious conclusion. Warrant cases introduce greater procedural rigor with mandatory charge-framing, detailed evidence recording, and the bifurcated consideration of discharge and trial. Sessions trials represent the apex of procedural elaboration, incorporating commitment proceedings, Public Prosecutor-led prosecution, and the most detailed evidence recording mechanisms.

The method of securing the accused’s presence differs markedly across these categories. In summons cases, a mere summons directing the accused to appear suffices. The accused is not arrested unless he fails to appear pursuant to the summons. In warrant cases, the Magistrate may issue either summons or warrant depending on the circumstances, but the gravity of the offense often necessitates warrant issuance. In sessions trials, since the accused has already been processed through Magistrate-level proceedings, he appears before the Sessions Court either in custody or on bail following commitment.

Rights of the Accused Across Different Trial Types

The rights afforded to the accused vary in their practical application across different trial types, though the fundamental rights remain constant. In summons cases, the accused enjoys the right to plead guilty and receive immediate sentencing, avoiding prolonged trial. The right to be tried in absentia in certain minor offenses reflects legislative pragmatism. However, the abbreviated evidence recording may sometimes limit the accused’s ability to thoroughly test prosecution evidence.

In warrant cases, the accused gains substantial procedural safeguards. The right to seek discharge at the preliminary stage under Section 239 or Section 245 provides an early exit mechanism if the prosecution case lacks merit. The formal framing of charges ensures the accused knows precisely what allegations he must meet. The detailed recording of evidence and the right to cross-examine witnesses comprehensively protect the accused’s right to fair trial.

Sessions trials afford the accused the most extensive procedural protections. The involvement of a Public Prosecutor ensures professional conduct of prosecution. The commitment proceedings before a Magistrate provide an initial scrutiny of the case. The discharge provision under Section 227 offers a significant safeguard against frivolous prosecutions. The elaborate evidence recording and the accused’s right to examine himself and call witnesses ensure comprehensive presentation of the defense case [7].

Recent Judicial Interpretations and Landmark Cases

Judicial Approach to Classification

Indian courts have consistently emphasized the importance of correct classification of Summons, Warrant, and Sessions Cases. The Supreme Court has held that the classification of an offense as a Summons Case or Warrant Case depends on the maximum punishment provided for the offense, not the actual punishment that may be imposed. This ensures uniformity and prevents manipulation through charge dilution. Courts have also clarified that when multiple offenses are charged, if even one offense falls within the Warrant Case or Sessions Case category, the entire matter must be tried under the procedure applicable to the more serious classification.

The distinction between discharge and acquittal has been the subject of extensive judicial scrutiny. Courts have held that an order of discharge is not equivalent to an acquittal and does not bar subsequent prosecution if fresh evidence emerges. The standard for discharge is lower than that for acquittal. At the discharge stage, the court need only be satisfied that there is no sufficient ground for proceeding with the trial, whereas acquittal requires the court to conclude that the prosecution has failed to prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

Constitutional Validity and Procedural Fairness

The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed that procedural classifications in the CrPC must uphold the constitutional guarantee of a fair trial. The Court has emphasized that while procedural differences exist among Summons Cases, Warrant Cases, and Sessions Cases, each framework must ensure the accused’s fundamental rights under Article 21 of the Constitution. These rights include the ability to be heard, to cross-examine witnesses, to present a defense, and to receive a reasoned judgment [8].

Courts have held that the summary nature of summons trial does not dilute the requirement of judicial scrutiny. Even in summons cases, the Magistrate must apply his mind to the evidence and cannot mechanically accept the prosecution version. The abbreviated recording of evidence must still capture the substance of testimony sufficiently to allow for meaningful appellate review. Similarly, in warrant cases and sessions trials, the elaborate procedures must not become instruments of oppression through unreasonable delays.

Practical Implications for Legal Practice

Strategic Considerations for Defense

Defense practitioners must adapt their strategies based on whether a case is a Summons, Warrant, or Sessions Case. In Summons Cases, early engagement with the prosecution to explore settlement possibilities may be prudent, given that many offenses are compoundable. The option for the accused to plead guilty and receive immediate sentencing may be advantageous if the evidence is overwhelming and the likely sentence is lenient. Additionally, the possibility of trial in absentia allows accused persons to avoid repeated court appearances in appropriate cases.

In warrant cases, the defense must focus intensively on the discharge stage. A well-crafted application for discharge under Section 239 or Section 245, highlighting deficiencies in the prosecution case, can result in early termination of proceedings. If discharge is denied, challenging the framing of charges becomes crucial, as the charge defines the scope of the trial. Meticulous cross-examination of prosecution witnesses is essential, given the detailed evidence recording that facilitates effective appellate review.

For sessions trials, defense preparation must begin at the commitment stage itself. Challenging the Magistrate’s commitment order may prevent the case from reaching the Sessions Court. Once committed, the discharge application under Section 227 requires thorough preparation, as it represents a critical juncture. The defense must be prepared for an elaborate trial involving multiple witnesses and extensive documentary evidence. Effective coordination with the accused for defense evidence presentation is vital.

Prosecution Perspectives and Challenges

From the prosecution standpoint, proper classification of offenses into Summons, Warrant, and Sessions Cases and meticulous compliance with procedural requirements are paramount. . In summons cases, prosecutors must present concise yet compelling evidence, recognizing that abbreviated procedures demand clarity and directness. The challenge lies in establishing guilt beyond reasonable doubt within a streamlined framework. Prosecutors must anticipate that accused persons may seek quick trials and be prepared for immediate evidence presentation.

In warrant cases, prosecutors face the burden of establishing sufficient grounds to proceed at multiple stages. The preliminary hearing for charge framing requires prosecutors to present prima facie evidence of guilt. Failure to do so results in discharge, which, while not barring fresh prosecution on new evidence, represents a setback. Prosecutors must ensure that all documents required under Section 207 are provided to the accused timely to avoid procedural challenges.

Sessions trial prosecutors confront the most demanding evidentiary standards. The Public Prosecutor must orchestrate the presentation of complex evidence, coordinate multiple witnesses, and respond to sophisticated defense challenges. The commitment stage requires careful preparation of the case diary and ensuring all documents are in order. At the trial stage, prosecutors must maintain coherence across numerous witness testimonies while anticipating and countering defense theories. The higher standard of proof and the detailed scrutiny by Sessions Judges demand excellence in prosecution craft [9].

Conclusion

The tripartite classification of criminal cases into summons cases, warrant cases, and sessions trials represents a fundamental organizing principle of Indian criminal procedure. This classification serves the dual objectives of efficient justice delivery and protection of accused persons’ rights. Summons cases, with their streamlined procedures, ensure that minor offenses do not clog the judicial system. Warrant cases, occupying the middle ground, balance procedural safeguards with reasonable expedition. Sessions trials, reserved for the gravest offenses, incorporate the most elaborate procedures to ensure that serious crimes receive thorough judicial examination.

Understanding these distinctions between Summons, Warrant, and Sessions Cases is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for anyone engaged with the criminal justice system. Legal practitioners must navigate these procedural frameworks skillfully to serve their clients effectively. Accused persons benefit from awareness of the procedural protections they can expect in each type of case. Judicial officers must apply these procedures consistently to ensure fairness and legal compliance. As Indian criminal law continues to evolve, the foundational principles underlying Summons, Warrant, and Sessions Cases remain central to achieving justice that is both swift and fair.

References

[1] Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Section 2(w).

[2] Drishti Judiciary. (n.d.). Warrant, Summons and Summary Trial under CrPC. Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/to-the-point/bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhita-&-code-of-criminal-procedure/warrant-summons-and-summary-trial

[3] Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Section 2(x).

[4] iPleaders. (2020). How is summon trial different from warrant trial. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/69101-2/

[5] Drishti Judiciary. (n.d.). Trial before Court of Session under CrPC. Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/to-the-point/bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhita-&-code-of-criminal-procedure/session-trial

[6] iPleaders. (2019). Trial before a Court of Session under Criminal Procedure Code. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/trial-before-a-cour-of-session/

[7] iPleaders. (2019). Summon Cases CrPc – Trial of Summon Case Under CrPc. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/summon-case-crpc/

[8] LawBhoomi. (2025). Types of Trial in CrPC. Available at: https://lawbhoomi.com/types-of-trial-in-crpc/

[9] Legal Service India. (n.d.). Trial Before A Court Of Session Under Code Of Criminal Procedure 1973. Available at: https://legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-1833-trial-before-a-court-of-session-under-code-of-criminal-procedure-1973.html

Whatsapp

Whatsapp