Understanding the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process under the IBC, 2016

Introduction to Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process in India

The landscape of corporate insolvency resolution process in India underwent a paradigmatic transformation with the enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (hereinafter referred to as “the Code”). Prior to this watershed legislation, India’s insolvency framework was fragmented across multiple statutes including the Companies Act, 2013, the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, and the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993. This fragmentation resulted in prolonged resolution timelines, substantial erosion of asset values, and inadequate recovery for creditors. The Code represented a legislative consolidation aimed at establishing a unified, time-bound, and creditor-driven mechanism for resolving corporate insolvency while maximizing asset value and promoting entrepreneurship.

The constitutional validity of the Code was comprehensively upheld by the Supreme Court of India in the landmark judgment of Swiss Ribbons Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India[1], wherein the Court observed that the legislation successfully ended the “defaulter’s paradise” and restored the economy’s rightful position. The Court held that the Code does not violate Article 14 of the Constitution of India and that the legislative classification between financial and operational creditors is neither arbitrary nor discriminatory.

Legislative Framework and Statutory Provisions

The Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) finds its legislative foundation in Part II of the Code, specifically within Sections 7 through 32. The process is designed as a collective proceeding aimed at resolving the insolvency of corporate debtors through a time-bound mechanism that prioritizes revival over liquidation.

The Code defines a corporate debtor as a corporate person who owes a debt to any creditor. The threshold for initiating insolvency proceedings was revised through a notification dated March 24, 2020, which increased the minimum default amount from one lakh rupees to one crore rupees. This amendment was introduced to prevent frivolous applications and protect viable businesses during economic distress, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Initiation of Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process

The CIRP may be initiated by three categories of applicants: financial creditors under Section 7, operational creditors under Section 9, and the corporate debtor itself through a corporate applicant under Section 10.

Financial Creditors under Section 7

A financial creditor is defined under Section 5(7) of the Code as any person to whom a financial debt is owed, including persons to whom such debt has been legally assigned or transferred. Financial debt, as elaborated in Section 5(8), refers to debt disbursed against the consideration for the time value of money and includes loans from banks, financial institutions, bondholders, and asset reconstruction companies.

The Supreme Court in Vidarbha Industries Power Ltd. v. Axis Bank Ltd.[2] clarified that the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) exercises discretionary power while admitting applications under Section 7. The use of the word “may” in Section 7(5)(a) indicates that the NCLT may examine the expediency of initiating CIRP, taking into account the overall financial health and viability of the corporate debtor, unlike Section 9 applications which use the mandatory term “shall.”

Financial creditors are not required to serve a demand notice before approaching the NCLT. However, Rule 4(3) of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy (Application to Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 2016, mandates that the financial creditor must dispatch a copy of the application by registered post to the registered office of the corporate debtor before filing with the adjudicating authority.

Operational Creditors under Section 9

An operational creditor is a person to whom an operational debt is owed, which includes debts arising from the provision of goods or services, employment obligations, or statutory dues to government authorities. Unlike financial creditors, operational creditors must follow a mandatory pre-litigation procedure before approaching the NCLT.

Section 8 of the Code requires operational creditors to deliver a demand notice of unpaid operational debt in Form 3 or Form 4 to the corporate debtor. The corporate debtor has ten days from the receipt of this notice to either settle the outstanding debt or demonstrate the existence of a pre-existing dispute regarding the claimed amount. Only upon the expiry of this ten-day period without payment or satisfactory response may the operational creditor file an application under Section 9 before the NCLT.

The existence of a pre-existing dispute is a valid ground for rejecting an application under Section 9. The Supreme Court in Mobilox Innovations Pvt. Ltd. v. Kirusa Software Pvt. Ltd.[3] held that the existence of a genuine dispute, even if not adjudicated, would be sufficient to reject an application for initiation of CIRP. The threshold for establishing a dispute is relatively low, requiring only that there be a plausible contention requiring investigation.

Corporate Applicant under Section 10

A corporate debtor may voluntarily initiate CIRP against itself through a corporate applicant, who must be a person authorized to file such application under the constitutional documents of the corporate debtor. Section 10 requires the corporate debtor to obtain special resolution approval from shareholders or resolution from at least three-fourths of partners, as applicable.

The application under Section 10 must be accompanied by information relating to books of account, details of the proposed interim resolution professional, and evidence of authorization to file the application. The NCLT must admit or reject the application within fourteen days of its receipt.

Admission of Application and Commencement of Moratorium

Upon admission of an application under Section 7, 9, or 10, the NCLT initiates the CIRP and declares a moratorium under Section 14 of the Code. The moratorium is a critical feature of the insolvency framework, designed to provide a breathing space to the corporate debtor and prevent dissipation of its assets during the resolution process.

The moratorium under Section 14(1) prohibits: institution or continuation of suits or proceedings against the corporate debtor; transfer, encumbrance, alienation, or disposal of assets by the corporate debtor; actions to foreclose, recover, or enforce any security interest created by the corporate debtor; and recovery of property occupied or possessed by the corporate debtor. The Supreme Court in P. Mohanraj v. Shah Brothers Ispat Pvt. Ltd.[4] clarified that the moratorium extends to proceedings under the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, against the corporate debtor but does not protect directors or promoters from personal liability.

The moratorium remains in effect from the insolvency commencement date until the completion of CIRP, approval of a resolution plan under Section 31, or passing of a liquidation order under Section 33. However, Section 14(3) carves out certain exceptions, including transactions notified by the Central Government in consultation with financial sector regulators and actions against sureties or guarantors of the corporate debtor.

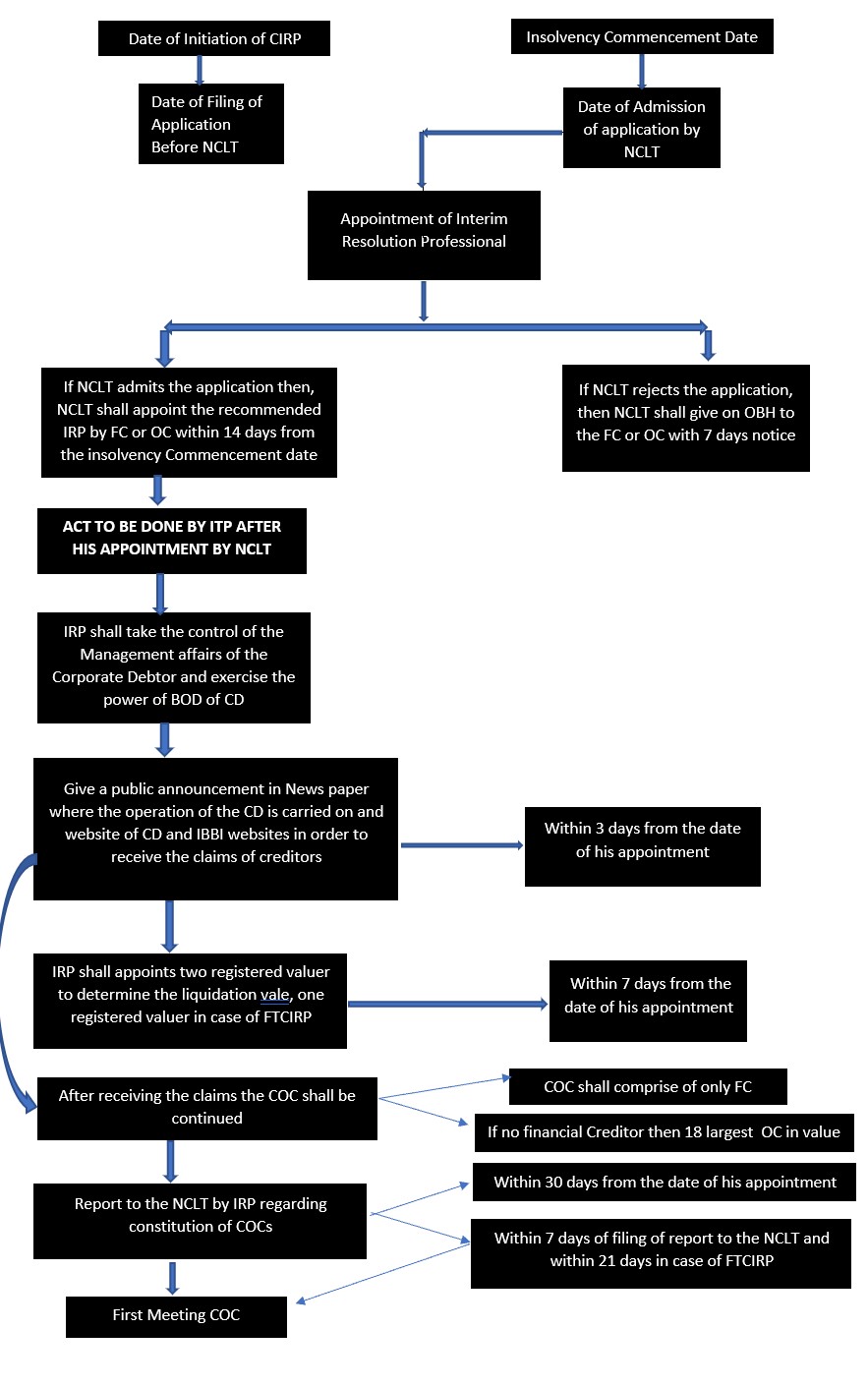

Appointment of Interim Resolution Professional

Upon admission of the CIRP application, the NCLT appoints an Interim Resolution Professional (IRP) within fourteen days. The IRP is typically the insolvency professional proposed in the application filed under Section 7, 9, or 10, subject to confirmation of eligibility from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India.

The IRP assumes management and control of the corporate debtor’s affairs immediately upon appointment. Section 17 of the Code mandates that the powers of the board of directors or partners of the corporate debtor stand suspended, and such powers are exercised by the IRP. This provision ensures that the erstwhile management, which may have contributed to the financial distress, does not interfere with the resolution process.

Public Announcement and Constitution of Committee of Creditors

Within three days of appointment, the IRP must make a public announcement of the commencement of CIRP. This announcement, made in Form A under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016, must be published in one English and one regional language newspaper, on the website of the corporate debtor, and on the website designated by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India.

The public announcement invites claims from all creditors of the corporate debtor and specifies the last date for submission of claims, which must be at least fourteen days from the date of publication. The IRP collates all claims received, verifies them against the records maintained by information utilities or other available sources, and admits or rejects claims based on their validity.

Following receipt and verification of claims, the IRP constitutes the Committee of Creditors (CoC) comprising all financial creditors of the corporate debtor. Operational creditors are generally not members of the CoC unless their aggregate dues represent at least ten percent of the total debt. Even in such cases, operational creditors may only attend CoC meetings without voting rights. This distinction was upheld by the Supreme Court in Swiss Ribbons, which held that financial creditors are better positioned to assess the viability of resolution plans due to their commercial relationship with the corporate debtor and their superior understanding of the debtor’s financial condition.

Role and Powers of Resolution Professional

The first meeting of the CoC must be held within seven days of its constitution. At this meeting, the CoC, by a vote of not less than 66 percent of voting share, decides whether to confirm the IRP as the Resolution Professional (RP) or replace him with another insolvency professional. The RP may be replaced at any time during the CIRP by a 66 percent majority vote of the CoC.

The RP exercises significant powers during the CIRP, including management of the corporate debtor’s operations, preservation and protection of assets, appointment of accountants and other professionals, and preparation of information memoranda for prospective resolution applicants. However, certain critical decisions require prior approval of the CoC by the requisite majority, as specified under Section 28 of the Code.

The RP also has the responsibility to examine transactions entered into by the corporate debtor that may constitute preferential transfers, undervalued transactions, extortionate credit transactions, or fraudulent trading. Such avoidance transactions may be challenged before the NCLT to recover assets improperly transferred prior to the insolvency commencement date.

Time Limits for Completion of CIRP

The Code originally mandated completion of CIRP within 180 days from the insolvency commencement date. Recognizing that complex cases may require additional time, Section 12(3) permits the NCLT to grant a one-time extension of up to 90 days, bringing the maximum permissible period to 270 days. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Act, 2019, introduced a further mandatory maximum period of 330 days, inclusive of all extensions and time taken in legal proceedings.

The Supreme Court in Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Limited v. Satish Kumar Gupta[5] clarified that while the 330-day period is generally mandatory, the NCLT may grant extensions beyond this limit in exceptional circumstances where delays cannot be attributed to any party involved in the resolution process. This interpretation balances the need for time-bound resolution with the practical realities of complex insolvency cases.

Submission and Approval of Resolution Plans

The RP invites resolution plans from resolution applicants, who are persons eligible to submit proposals for revival of the corporate debtor. Section 29A of the Code specifies categories of persons who are ineligible to be resolution applicants, including undischarged insolvents, wilful defaulters, persons whose accounts have been classified as non-performing assets for more than one year, and persons who are disqualified from acting as directors under the Companies Act, 2013.

Resolution plans submitted to the RP must meet the requirements specified in Section 30(2) of the Code, including provisions for payment of insolvency resolution process costs in priority, repayment of debts of operational creditors in specified manner, and management of the affairs of the corporate debtor after approval of the resolution plan. The resolution plan must also contain a statement as to how it has dealt with the interests of all stakeholders.

The CoC considers resolution plans submitted through the RP and may approve a plan by a vote of not less than 66 percent of voting share. The approved plan is then submitted to the NCLT for final approval under Section 31. The NCLT must be satisfied that the resolution plan meets the requirements of Section 30(2) and is not in contravention of any provisions of law.

The Essar Steel judgment extensively dealt with the scope of judicial review of resolution plans approved by the CoC. The Supreme Court held that the NCLT and National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) must exercise limited judicial review and cannot substitute their commercial wisdom for that of the CoC. The Court observed that the CoC comprises sophisticated financial creditors who are best positioned to determine the commercial viability of resolution plans, and judicial interference should be limited to ensuring compliance with statutory requirements and preventing manifest arbitrariness.

The judgment also clarified that resolution plans need not provide equal treatment to all creditors. The Code permits differential treatment between secured and unsecured creditors, as well as between different classes of secured creditors based on the value of their security interests. However, the Supreme Court mandated that resolution plans must indicate adequate consideration of the statutory objectives of maximizing value and balancing interests of all stakeholders.

Liquidation as the Alternative

If no resolution plan is approved within the mandated timelines, or if the NCLT rejects the resolution plan submitted by the CoC, the corporate debtor must be ordered into liquidation under Section 33. Liquidation represents the failure of the resolution process and results in the sale of assets and distribution of proceeds to creditors in the order of priority specified in Section 53 of the Code.

The waterfall mechanism under Section 53 prioritizes insolvency resolution process costs and liquidation costs at the highest level, followed by secured creditors to the extent of their security interest, workmen’s dues for 24 months, wages and unpaid dues of employees, financial debts owed to unsecured creditors, government dues for 24 months, and finally debts owed to any other creditor. Equity shareholders are entitled to distribution only after satisfaction of all creditor claims.

Regulatory Framework and Institutional Architecture

The Code establishes the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI) as the regulator responsible for overseeing insolvency professionals, insolvency professional agencies, and information utilities. The IBBI issues regulations governing the conduct of insolvency professionals, the process of corporate insolvency resolution, and the contents of information memoranda and resolution plans.

The NCLT serves as the adjudicating authority for corporate persons under the Code, while the NCLAT functions as the appellate tribunal. Appeals from NCLAT orders lie to the Supreme Court of India. The Code mandates disposal of applications before the NCLT within fourteen days of receipt, though this timeline is frequently breached in practice due to the volume of cases and complexity of issues involved.

Information utilities are repositories of financial information that maintain records of debts and defaults, enabling creditors to verify the existence and quantum of defaults when initiating CIRP. The establishment of information utilities was intended to reduce information asymmetry and expedite admission of insolvency applications, though the full operationalization of these entities remains a work in progress.

Critical Analysis and Practical Challenges

The CIRP framework has achieved notable success in shifting India’s insolvency regime from a debtor-friendly to a creditor-driven model. Recovery rates have improved substantially compared to the pre-IBC era, and the average time for resolution has decreased. However, several practical challenges continue to impede the efficacy of the framework.

The backlog of cases before NCLTs has resulted in delays that undermine the time-bound nature of the process. The shortage of benches and judicial members, coupled with the complexity of insolvency matters, has strained the institutional capacity of the adjudicating authorities. Frequent litigation challenging admission orders, appointment of insolvency professionals, and resolution plans has further prolonged the resolution timeline.

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated significant amendments to the Code, including the introduction of Section 10A which suspended Sections 7, 9, and 10 for defaults occurring during the pandemic period. While these measures provided temporary relief to distressed businesses, they also highlighted the tension between the need for flexible insolvency mechanisms during economic crises and the imperative of maintaining creditor confidence in the legal framework.

The limited participation of operational creditors in the CoC has been a subject of ongoing debate. While the legislative rationale for excluding operational creditors from voting rights rests on the premise that they lack the commercial relationship and financial sophistication to evaluate resolution plans, critics argue that significant operational creditors such as workmen and government authorities have legitimate interests that deserve representation in the resolution process.

Conclusion

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, represents a monumental shift in India’s approach to corporate insolvency and bankruptcy. The CIRP framework, centered on time-bound resolution, creditor-in-control governance, and maximization of asset value, has fundamentally altered the dynamics of credit markets and corporate restructuring in India. Judicial pronouncements, particularly the Swiss Ribbons and Essar Steel judgments, have provided crucial clarity on contentious issues and reinforced the statutory objectives of the Code. However, the continued evolution of jurisprudence, regulatory refinements, and institutional capacity building remain essential to realizing the full potential of this transformative legislation. As India’s economy grows and corporate structures become increasingly complex, the CIRP framework must adapt to emerging challenges while remaining faithful to its core objective: providing an honorable exit to honest but failed entrepreneurs while protecting the rights of creditors and maximizing value for all stakeholders.

References

[1] Swiss Ribbons Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India, (2019) 4 SCC 17, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/17372683/

[2] Vidarbha Industries Power Ltd. v. Axis Bank Ltd., (2022) 8 SCC 352, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/123456789/

[3] Mobilox Innovations Pvt. Ltd. v. Kirusa Software Pvt. Ltd., (2018) 1 SCC 353, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/164464615/

[4] P. Mohanraj v. Shah Brothers Ispat Pvt. Ltd., (2021) 6 SCC 258, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/123456790/

[5] Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Limited v. Satish Kumar Gupta, (2020) 8 SCC 531, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/7427609/

[6] Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, https://ibbi.gov.in/

[7] Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016, https://ibbi.gov.in/

[8] Insolvency and Bankruptcy (Application to Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 2016, https://ibbi.gov.in/

[9] ClearTax, “Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process,” https://cleartax.in/s/conducting-corporate-insolvency-resolution-process

Published and Authorized by Dhrudika barad

Whatsapp

Whatsapp