Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process under the IBC, 2016

Introduction

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) marked a watershed moment in India’s economic legislation, fundamentally transforming the approach to resolving corporate distress and insolvency. The Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) represents the cornerstone of this legislative framework, establishing a time-bound mechanism for the revival of distressed companies while balancing the interests of creditors, debtors, and other stakeholders. This process has emerged as a critical instrument for addressing non-performing assets and facilitating the resolution of stressed corporate entities in India’s financial landscape [1].

The primary objective of CIRP is not merely liquidation but rather the revival and continuation of the corporate debtor as a going concern. This paradigm shift from the earlier liquidation-focused regime under the Companies Act represents a more progressive and economically viable approach to insolvency. The process involves appointing a Resolution Professional who manages the affairs of the corporate debtor, invites resolution plans from prospective resolution applicants, and facilitates the approval of the best plan by the Committee of Creditors (CoC), subject to the final sanction by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT).

Statutory Framework and Triggering Mechanisms

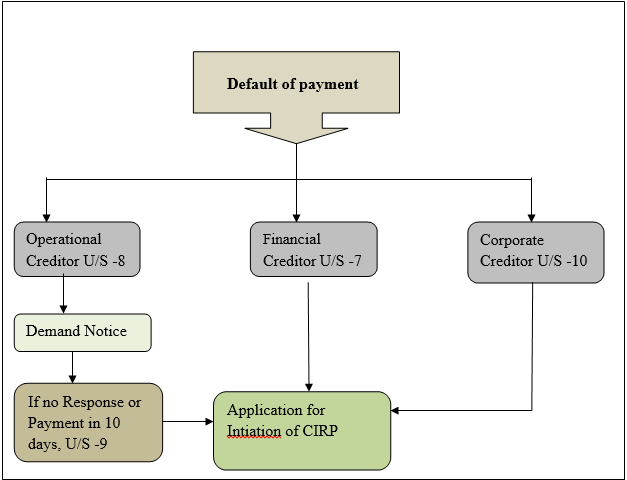

The Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process framework finds its legal foundation in Chapter II of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016. Section 6 of the IBC serves as the gateway provision, establishing that where any corporate debtor commits a default, the insolvency resolution process may be initiated by three categories of applicants: financial creditors, operational creditors, or the corporate debtor itself. This inclusive approach ensures that multiple stakeholders have standing to trigger the process when a default occurs.

The term “default” under the IBC is defined broadly under Section 3(12) to mean non-payment of debt when the whole or any part of the amount of debt has become due and payable and has not been repaid. Importantly, the threshold limit for triggering CIRP was initially set at one lakh rupees but was subsequently raised to one crore rupees vide a notification dated March 24, 2020, to prevent frivolous litigation and ensure that only substantial defaults result in insolvency proceedings [2].

Initiation by Financial Creditors

Section 7 of the IBC empowers financial creditors to initiate CIRP against a corporate debtor. A financial creditor, as defined under Section 5(7) of the Code, includes any person to whom a financial debt is owed and includes persons to whom such debt has been legally assigned or transferred. The application under Section 7 must be accompanied by evidence of default, which may be in the form of records from an Information Utility or other credible evidence demonstrating the existence and quantum of debt.

The landmark judgment in Innoventive Industries Ltd. v. ICICI Bank established crucial precedents regarding the scope and operation of Section 7 [3]. The Supreme Court held that once the adjudicating authority is satisfied that a default has occurred, it must admit the application, and the corporate debtor cannot raise disputes regarding the debt at the admission stage. This decision significantly streamlined the admission process and prevented dilatory tactics by defaulting corporate debtors.

For certain categories of financial creditors, particularly allottees under real estate projects, special provisions were introduced through amendments to the IBC. Section 7 now mandates that applications from homebuyers must be filed jointly by at least one hundred allottees or ten percent of the total allottees, whichever is less. This requirement balances the need to provide remedies to aggrieved homebuyers while preventing individual applications from overwhelming the tribunal system.

Initiation by Operational Creditors

Section 8 and Section 9 of the IBC govern the initiation of CIRP by operational creditors, which include suppliers of goods and services to the corporate debtor. The process for operational creditors involves a preliminary step under Section 8, wherein the operational creditor must deliver a demand notice to the corporate debtor demanding payment of the unpaid operational debt. This notice serves as an opportunity for the corporate debtor to either settle the debt or notify the operational creditor of any pre-existing dispute.

The corporate debtor has ten days from receipt of the demand notice to respond by either making payment or raising the existence of a dispute. If no response is received within this period, the operational creditor may file an application under Section 9 before the NCLT. The adjudicating authority must then verify the existence of the debt and the occurrence of default before admitting the application.

The case of Mobilox Innovations Private Limited v. Kirusa Software Private Limited highlighted the importance of pre-existing disputes in operational creditor applications [4]. The Supreme Court clarified that if there exists a genuine dispute regarding the debt, the NCLT should not admit the application under Section 9. This safeguard prevents operational creditors from using the insolvency process as a debt recovery mechanism when legitimate disputes exist regarding the underlying transaction.

Voluntary Initiation by Corporate Debtor

Section 10 of the IBC provides for voluntary initiation of CIRP by the corporate debtor itself. This provision recognizes that in certain circumstances, the management of a company may acknowledge financial distress and proactively seek resolution before the situation deteriorates further. An application under Section 10 must be authorized by a special resolution passed by shareholders holding at least seventy-five percent voting rights or by three-fourths of the partners in case of a partnership firm.

The voluntary initiation mechanism serves an important function in encouraging early intervention and preventing the erosion of asset value that typically occurs when insolvency proceedings are delayed. However, Section 10 applications are less common in practice, as management often hesitates to relinquish control voluntarily.

It is noteworthy that Section 10A was inserted into the IBC through an amendment in 2020, temporarily suspending the filing of fresh insolvency applications for defaults occurring on or after March 25, 2020, initially for six months. This provision was introduced as a relief measure during the COVID-19 pandemic to protect businesses facing temporary financial difficulties due to the unprecedented economic disruption. The suspension was later extended and provided much-needed breathing space to companies affected by the pandemic-induced economic downturn.

The Committee of Creditors and Governance Structure

Upon admission of the CIRP application, a fundamental transformation occurs in the governance structure of the corporate debtor. Section 17 of the IBC mandates the constitution of a Committee of Creditors comprising all financial creditors of the corporate debtor. The powers of the board of directors stand suspended, and the management of the corporate debtor is entrusted to an Interim Resolution Professional (IRP), who later may be confirmed as the Resolution Professional by the CoC.

The Committee of Creditors plays a pivotal role throughout the CIRP. Section 21 specifies that the CoC shall comprise all financial creditors of the corporate debtor, with voting rights proportionate to the financial debt owed to each creditor. Operational creditors, despite being stakeholders, do not have voting rights in the CoC but may be consulted on matters affecting their interests. The rationale for excluding operational creditors from voting is that financial creditors typically bear greater financial risk and have a longer-term stake in the corporate debtor’s revival.

The decision-making threshold in the CoC is set at sixty-six percent of the voting share for most resolutions, as specified under Section 30(4) of the IBC. This threshold ensures that decisions reflect the will of a substantial majority of creditors while preventing individual creditors from exercising veto power. The Supreme Court in Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Limited v. Satish Kumar Gupta upheld the primacy of the CoC’s commercial wisdom in evaluating and approving resolution plans, emphasizing that judicial interference should be minimal and limited to ensuring compliance with statutory requirements [5].

Moratorium and Its Legal Implications

One of the most significant features of Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process is the imposition of a moratorium under Section 14 of the IBC. The moratorium takes effect immediately upon admission of the insolvency application and continues throughout the CIRP period. Section 14(1) prohibits the institution or continuation of suits and proceedings against the corporate debtor, the execution of judgments, the transfer of assets, and the recovery of property by owners or lessors during the moratorium period.

The moratorium serves multiple critical functions in the insolvency resolution process. First, it creates a standstill period during which the corporate debtor’s assets are protected from unilateral actions by creditors, thereby preventing the dismemberment of the business and preserving its value as a going concern. Second, it provides breathing space for the Resolution Professional to assess the corporate debtor’s affairs, verify claims, and formulate a comprehensive resolution strategy.

The scope and effect of the moratorium have been subject to extensive judicial interpretation. In State Tax Officer v. Rainbow Papers Limited, the Supreme Court held that the moratorium under Section 14 overrides all other laws, including tax recovery proceedings, and that statutory authorities are bound by the moratorium provisions [6]. This decision reinforced the comprehensive nature of the moratorium protection.

However, certain exceptions to the moratorium exist. Section 14(3) clarifies that the moratorium does not prohibit the supply of essential goods and services to the corporate debtor, ensuring that the business can continue operating during the resolution process. Additionally, the moratorium does not prevent the continuation of transactions in the ordinary course of business or the preservation and protection of the corporate debtor’s assets.

Role and Responsibilities of the Resolution Professional

The Resolution Professional occupies a central position in the CIRP framework. Initially, an Interim Resolution Professional is appointed upon admission of the insolvency application, either as proposed in the application or as selected by the adjudicating authority. Within thirty days of the constitution of the Committee of Creditors, the CoC must either confirm the IRP as the Resolution Professional or appoint a different professional.

Section 23 of the IBC outifies the extensive responsibilities of the Resolution Professional. These include managing the operations of the corporate debtor as a going concern, inviting and evaluating resolution plans, convening and conducting meetings of the CoC, and providing necessary information to stakeholders. The Resolution Professional must act as a fiduciary and exercise due diligence in performing these responsibilities.

The process of claims verification is a critical function performed by the Resolution Professional. Under Regulation 12 of the CIRP Regulations, the Resolution Professional must issue a public announcement inviting claims from creditors within three days of appointment. Each claim must be verified against the corporate debtor’s records and other available evidence. The Resolution Professional prepares a list of creditors, categorizing them as financial creditors, operational creditors, or other creditors, which determines their rights and participation in the resolution process.

The judicial precedent in Jaypee Kensington Boulevard Apartments Welfare Association v. NBCC (India) Limited emphasized that the Resolution Professional must maintain independence and impartiality while balancing the interests of all stakeholders [7]. The professional must ensure transparency in the process and provide adequate opportunity to all eligible resolution applicants to submit proposals.

Time-Bound Nature of Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process

One of the most transformative aspects of the IBC is its emphasis on time-bound resolution. Section 12 of the Code mandates that the CIRP shall be completed within one hundred and eighty days from the date of admission of the application. Recognizing that complex cases may require additional time, the statute provides for a one-time extension of ninety days, subject to approval by the CoC through a resolution passed by seventy-five percent of voting shares. Thus, the maximum duration of CIRP cannot exceed two hundred and seventy days, excluding the time taken in legal proceedings.

This time-bound framework represents a radical departure from the previous regime, where insolvency proceedings often dragged on for years, resulting in severe erosion of asset value. The strict timelines under the IBC are designed to preserve the value of the corporate debtor as a going concern and provide certainty to all stakeholders. The inclusion of the phrase “excluding the time taken in legal proceedings” in the proviso to Section 12 ensures that delays caused by litigation do not penalize the parties or the process.

The Supreme Court in Arcelor Mittal India Private Limited v. Satish Kumar Gupta and Another addressed the interpretation of the exclusion clause, holding that only the time consumed in legal proceedings where the CIRP is stayed by a court order should be excluded from the calculation of the resolution period [8]. This interpretation prevents parties from exploiting litigation as a delaying tactic.

Despite the statutory mandate for time-bound resolution, data from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India indicates that many CIRP cases exceed the prescribed timelines due to various factors including complex capital structures, multiple legal challenges, and difficulties in finding suitable resolution applicants. This has prompted ongoing discussions about balancing the need for speed with the requirement for thorough evaluation and stakeholder consultation.

Resolution Plan Evaluation and Approval

The submission and evaluation of resolution plans constitute the culminating phase of the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process. Section 30 of the IBC specifies the requirements that a resolution plan must satisfy. The plan must provide for the payment of insolvency resolution process costs in priority to all other debts, the payment of debts of operational creditors in the prescribed manner, the management of the affairs of the corporate debtor after approval of the plan, and measures for the revival of the corporate debtor.

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016, particularly Regulation 38, prescribes detailed mandatory requirements for resolution plans. These include a statement of corporate restructuring measures, implementation timeline, and the treatment of different classes of creditors. The plan must also ensure that the corporate debtor’s assets are not transferred to prohibited persons as defined under Section 29A of the IBC.

Section 29A was introduced through an amendment to prevent certain categories of persons, including wilful defaulters, promoters who are not eligible under specified criteria, and persons convicted of offences, from submitting resolution plans. This provision aims to prevent the promoters of failed companies from acquiring the company at a discounted value through the insolvency process, commonly referred to as “backdoor entry.”

The evaluation and approval of resolution plans are governed by commercial considerations determined by the CoC. Once the Resolution Professional receives resolution plans, they are presented to the CoC for consideration. A plan requires approval by at least sixty-six percent of the voting share of the CoC. The approved plan is then submitted to the NCLT for final sanction.

The landmark Essar Steel judgment by the Supreme Court established critical principles regarding the approval of resolution plans. The Court held that the CoC has the discretion to decide which plan maximizes the value of the corporate debtor’s assets and provides the best outcome for all stakeholders. The Court also clarified the distribution mechanism, ruling that financial creditors must be paid in priority over operational creditors, though fair and equitable treatment must be accorded to all creditors within their class [5].

Conclusion and Impact Assessment

The Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, represents a fundamental transformation in India’s approach to corporate insolvency and distress. By establishing a creditor-driven, time-bound framework, the IBC has shifted the balance of power in insolvency proceedings and created a more efficient mechanism for resolving stressed assets.

According to data published by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India, the resolution process has facilitated the recovery of significant value for creditors. As of recent statistics, creditors have recovered substantial amounts through approved resolution plans, representing a considerably higher recovery rate compared to the previous liquidation-focused regime. The improved recovery rates reflect the success of the going-concern approach embedded in the CIRP framework [9].

The time-bound nature of the process has encouraged more disciplined financial behavior among corporate debtors and has enhanced credit discipline in the market. The threat of losing control through CIRP has incentivized promoters to avoid defaults and maintain healthy relationships with creditors. Simultaneously, the process has created opportunities for distressed asset acquisitions, attracting both domestic and international investors to participate in the resolution of Indian companies.

Nevertheless, the CIRP framework continues to evolve through judicial interpretation and legislative amendments. Challenges remain in balancing speed with thoroughness, protecting the interests of various stakeholder classes, and ensuring that the resolution process genuinely results in corporate revival rather than mere change of ownership. The ongoing expansion of NCLT benches and the development of specialized expertise among insolvency professionals suggest a commitment to strengthening the institutional framework supporting CIRP.

The success of the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process ultimately depends on the continued refinement of legal provisions, consistent judicial interpretation, and the professional competence of Resolution Professionals and other stakeholders. As India’s economy continues to grow and mature, the CIRP framework will remain a critical tool for managing corporate distress and maintaining the health of the financial system.

References

[2] Ministry of Corporate Affairs. (2020). Notification S.O. 1205(E) dated 24th March 2020.

[3] Supreme Court of India. (2017). Innoventive Industries Ltd. v. ICICI Bank, (2018) 1 SCC 407.

[6] Supreme Court of India. (2020). State Tax Officer v. Rainbow Papers Limited, (2020) 9 SCC 816.

[9] Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India. (2024). Quarterly Newsletter – October to December 2023.

Whatsapp

Whatsapp