Introduction

Modern food supply chains represent complex, multi-tiered networks involving numerous entities from primary producers to end retailers. In India, where traditional and modern food systems coexist, determining legal responsibility for food safety violations presents significant challenges for regulators, legal practitioners, and food business operators. The Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 (FSS Act) established a comprehensive regulatory framework for food safety in India but leaves important questions regarding liability distribution across complex supply chains. This article examines how the FSS Act allocates legal liability among various stakeholders in multi-tier food supply chains, analyzing statutory provisions, corporate liability mechanisms, practical responsibility distribution, defense strategies, and evolving judicial interpretations. Understanding these legal dimensions is crucial for food business operators seeking to manage compliance risks and for regulators designing effective enforcement strategies.

Statutory Basis for Multi-Tier Liability

The Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 provides the primary legislative foundation for food safety liability in India. Several key provisions establish the basis for multi-tier liability across food supply chains. Section 3(n) of the Act defines “food business” broadly as “any undertaking, whether for profit or not and whether public or private, carrying out any of the activities related to any stage of manufacture, processing, packaging, storage, transportation, distribution of food, import and includes food services, catering services, sale of food or food ingredients.” This expansive definition encompasses virtually every entity in the food supply chain, creating a comprehensive regulatory scope.

Section 27 of the FSS Act establishes the fundamental liability framework, stating that “A food business operator or importer shall be liable for any article of food which is imported, manufactured, stored, sold or distributed by him.” This provision creates direct liability for food business operators regarding products under their control, regardless of their position in the supply chain. Notably, the provision does not limit liability to only the entity directly responsible for a violation, creating the potential for overlapping liability among multiple supply chain participants.

Section 66 of the Act specifically addresses attribution of liability in cases involving multiple parties, stipulating that “Where an offense under this Act which has been committed by a company, every person who at the time the offense was committed was in charge of, and was responsible to, the company for the conduct of the business of the company, as well as the company, shall be deemed to be guilty of the offense and shall be liable to be proceeded against and punished accordingly.” This provision extends liability beyond the corporate entity to individual officers, creating personal accountability for food safety violations.

The 2008 Food Safety and Standards Rules further clarify liability frameworks, with Rule 2.1.2 specifying that “A food business operator, shall be liable for any failure to comply with any of the general hygienic and sanitary practices, requirements and any other requirements” specified in various schedules. This explicit attribution of liability to operators reinforces the FSS Act’s approach to holding food businesses accountable for compliance throughout their operations.

Corporate Liability Provisions

Corporate liability within multi-tier food supply chains presents particular complexity due to the involvement of various legal entities with different organizational structures. Section 66 of the FSS Act establishes a comprehensive framework for corporate liability, ensuring that both companies and their responsible individuals face appropriate legal consequences for food safety violations.

The provision establishes that when a company commits an offense under the Act, every person who was in charge of and responsible for the company’s business conduct at the time shall be deemed guilty alongside the company itself. This creates a dual liability structure targeting both the corporate entity and its decision-makers. However, the provision includes an important qualification: “Provided that nothing contained in this sub-section shall render any such person liable to any punishment provided in this Act, if he proves that the offense was committed without his knowledge or that he exercised all due diligence to prevent the commission of such offense.”

This knowledge and due diligence defense provides important protection for corporate officers who implement appropriate food safety systems. The burden of proof, however, rests with the individual seeking to establish this defense, creating a strong incentive for proactive compliance efforts.

For multi-location companies, the first proviso to Section 66 creates a more targeted liability approach: “Provided that where a company has different establishments or branches or different units in any establishment or branch, the concerned Head or the person in-charge of such establishment, branch, unit nominated by the company as responsible for food safety shall be liable for contravention in respect of such establishment, branch or unit.” This provision allows large corporations to designate specific individuals as food safety officers for particular facilities, concentrating liability on those with direct oversight responsibility rather than distant corporate executives.

The penalty structure under the FSS Act establishes graduated penalties based on offense severity. Sections 50 through 67 outline specific penalties for various violations, ranging from manufacturing adulterated food to misleading advertisements. For instance, under Section 51, manufacturing or selling sub-standard food carries a penalty up to five lakh rupees, while Section 59 establishes that unsafe food causing death can result in imprisonment for a term “which shall not be less than seven years but which may extend to imprisonment for life” and a fine extending to ten lakh rupees. This graduated approach creates proportionate consequences based on violation severity and resulting harm.

A landmark Supreme Court ruling in Ram Nath v. State of Uttar Pradesh (Criminal Appeal No. 472 of 2012) significantly impacted the enforcement landscape by establishing FSSAI’s primacy in food safety enforcement. The Court held that the FSS Act should prevail over general provisions of the Indian Penal Code regarding food adulteration, noting that “there were various exhaustive and procedural provisions in the FSSAI which dealt with offences concerning unsafe food.” This ruling reinforced the comprehensive nature of the FSS Act’s liability framework and clarified jurisdictional questions regarding food safety enforcement.

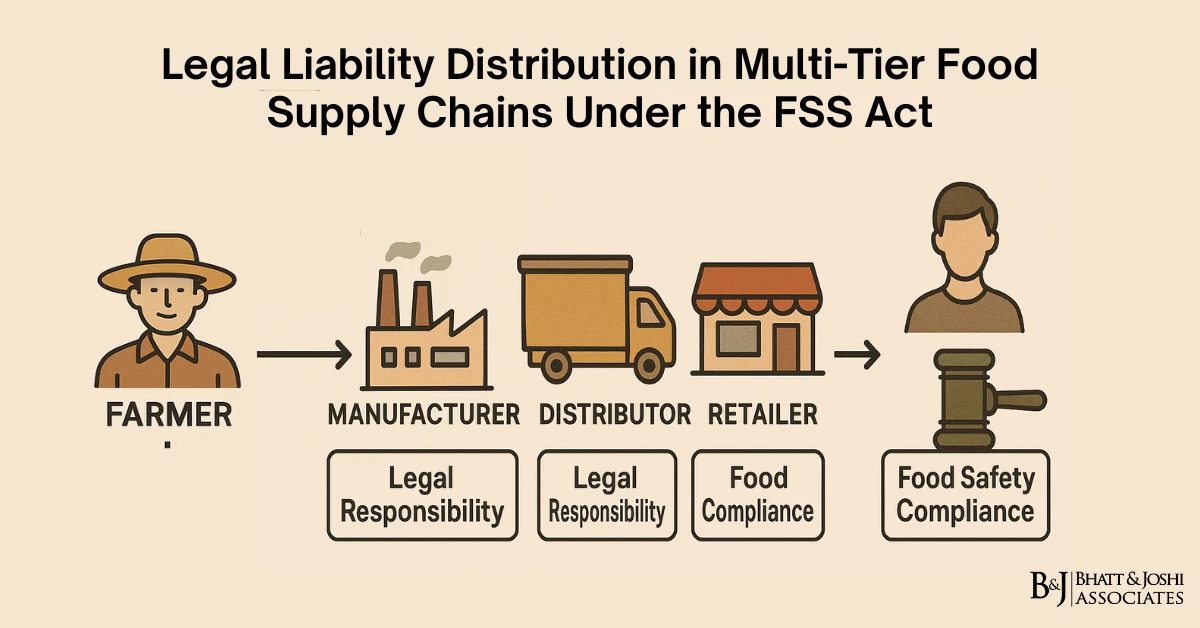

Distribution of Liability in Food Supply Chains under FSS Act

The practical liability distribution in multi-tier food supply chains reflects both statutory provisions and real-world operational dynamics. The FSS Act creates distinct but often overlapping responsibilities for different supply chain participants, establishing a comprehensive safety net to ensure consumer protection.

Manufacturer responsibilities constitute the foundation of food safety liability. Under Section 26 of the FSS Act, manufacturers must ensure that articles of food manufactured, stored, sold, or distributed are in compliance with the requirements of the Act and regulations. This creates primary liability for safety, quality, and labeling compliance. Manufacturers must also implement appropriate recall procedures when issues arise, as specified in the Food Safety and Standards (Food Recall Procedure) Regulations, 2017. These regulations establish detailed responsibilities for identifying, notifying, and retrieving non-compliant products, creating significant liability exposure for manufacturers who fail to implement effective recall systems.

Distributor and retailer obligations create a second tier of liability. While distributors and retailers may have less direct control over product formulation or manufacturing conditions, they bear significant verification and due diligence responsibilities. Section 25 requires importers to ensure imported food articles comply with the Act and regulations. Similarly, Section 27 establishes that food business operators are liable for food articles they distribute or sell. This creates an affirmative obligation to verify the compliance of products they handle rather than merely serving as passive intermediaries.

A notable judicial interpretation of “responsibility to know” in multi-tier distribution systems emerged in a 2019 case involving contaminated spices distributed through multiple intermediaries. The Food Safety Appellate Tribunal rejected a distributor’s defense that they were unaware of adulteration, establishing that distributors have an affirmative duty to verify product quality through appropriate testing rather than relying solely on supplier assurances. The tribunal stated: “The distributor cannot escape liability merely by claiming lack of knowledge when reasonable testing would have revealed the non-compliance.”

This cascading liability model creates overlapping responsibilities, potentially holding multiple entities accountable for the same violation. This approach reflects a regulatory philosophy prioritizing consumer protection through comprehensive oversight rather than limiting liability to single points of failure within complex supply chains.

Defense Mechanisms and Due Diligence

Given the extensive liability exposure created by the FSS Act, effective defense mechanisms and due diligence strategies are essential for food business operators seeking to manage legal risks. The FSS Act provides certain statutory defenses, most notably the “due diligence” defense established in the proviso to Section 66, which exempts individuals from liability if they can prove “the offense was committed without his knowledge or that he exercised all due diligence to prevent the commission of such offense.”

The legal standards for establishing adequate precautions have been clarified through adjudicatory decisions. Food Safety Appellate Tribunals have generally required documentation of systematic approaches rather than casual or occasional quality checks. A comprehensive due diligence defense typically includes: (1) documented quality assurance programs; (2) regular supplier audits; (3) appropriate testing protocols; (4) staff training records; (5) traceability systems; and (6) documented corrective actions when issues arise.

The Food Safety and Standards (Food Recall Procedure) Regulations, 2017 establish specific documentation requirements that factor into liability defenses. These include maintenance of distribution records, batch/lot identification systems, supplier verification documentation, customer complaint handling procedures, and recall capability demonstrations. Compliance with these documentation requirements not only facilitates effective recalls but also helps establish due diligence defenses if safety issues arise.

A notable case illustrating a successful defense based on documented quality control systems involved a retailer facing penalties after selling a product subsequently found to contain unauthorized additives. The retailer successfully defended against penalties by demonstrating comprehensive supplier verification protocols, including supplier certification requirements, periodic testing of high-risk products, and prompt action upon discovering the violation. The adjudicating officer accepted this defense, noting that “the respondent has established systems reasonably expected to prevent such violations and took appropriate action upon discovery.”

For food business operators, implementing robust preventive controls and documentation systems serves dual purposes: preventing food safety violations and establishing legal defenses if issues arise despite precautions. The emphasis on documented systems rather than mere assertions of care reflects the FSS Act’s focus on verifiable compliance rather than good intentions.

Recent Judicial Interpretations

Recent judicial interpretations have significantly shaped the landscape of liability distribution in multi-tier food supply chains, clarifying statutory ambiguities and establishing important precedents for future enforcement actions. Supreme Court precedents have particularly influenced the scope of liability in food supply chains.

The previously mentioned Ram Nath v. State of Uttar Pradesh case established the primacy of the FSS Act over the Indian Penal Code in food adulteration matters, but it also addressed broader questions about the comprehensiveness of the FSS Act’s liability framework. The Court emphasized that the FSS Act “has various exhaustive and procedural provisions” dealing with food safety offenses, and Section 89 provides an overriding effect over other food-related laws. This ruling reinforced the Act’s status as a specialized, comprehensive regime for food safety enforcement, including its liability provisions.

High Court interpretations have shown some regional variations in liability enforcement approaches. For instance, the Bombay High Court has generally taken a strict approach to distributor liability, frequently upholding penalties against distributors even when they claim lack of knowledge about product defects. In contrast, the Delhi High Court has occasionally shown greater receptivity to due diligence defenses, particularly for retailers who can demonstrate comprehensive supplier verification systems.

Adjudicating Officer decisions under the FSS Act have created a substantial body of administrative case law regarding liability distribution in multi-tier food supply chains. These decisions frequently address practical questions about reasonable expectations for different supply chain participants. For instance, a 2023 decision by an Adjudicating Officer in Gujarat established that while small retailers cannot reasonably be expected to conduct laboratory testing of all products, they must at minimum verify FSSAI licensing of suppliers, maintain basic traceability records, and conduct visual inspections for obvious defects or labeling issues.

Another important judicial interpretation addressed liability for imported ingredients used in domestically manufactured products. In a 2022 case involving a food manufacturer using imported additives that were later found to violate standards, both the importer and the manufacturer using the ingredients faced penalties. The adjudicating authority rejected the manufacturer’s argument that they should not be liable for ingredient non-compliance, stating that “manufacturers bear responsibility for verifying the compliance of all ingredients used in their products, regardless of source.”

Collectively, these judicial interpretations have reinforced several key principles: (1) FSS Act liability provisions create overlapping responsibilities across the supply chain rather than isolating liability to single entities; (2) all supply chain participants have affirmative verification obligations proportionate to their role and resources; and (3) documented due diligence systems provide the most effective liability defense for food business operators.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The distribution of legal liability in multi-tier food supply chains under the FSS Act reflects a regulatory philosophy prioritizing comprehensive consumer protection through overlapping responsibility structures. Rather than limiting liability to entities directly causing violations, the Act creates cascading obligations that hold multiple supply chain participants accountable for ensuring product safety and compliance. This approach recognizes the complexity of modern food systems and the difficulty of isolating safety responsibility to single points in interconnected networks.

For food business operators, several implications emerge from this liability framework. First, contractual risk allocation through indemnification provisions and insurance requirements becomes essential for managing liability exposure, though such arrangements do not eliminate statutory obligations to regulators. Second, supplier verification programs take on heightened legal significance, serving not merely as quality assurance measures but as essential components of liability defense. Third, documentation systems must be designed with potential legal proceedings in mind, maintaining records that would satisfy adjudicating authorities’ expectations for due diligence evidence.

From a regulatory perspective, the multi-tier liability approach creates both advantages and challenges. The overlapping responsibility model reduces the likelihood of safety gaps by creating multiple checkpoints throughout the supply chain. However, this approach also raises questions about enforcement efficiency and proportional punishment. When multiple entities face penalties for the same violation, regulators must balance accountability against potential market disruptions and enforcement resource limitations.

Legal practitioners advising food business clients must develop nuanced strategies tailored to their clients’ specific supply chain positions. Manufacturer representation requires particular attention to product development protocols, hazard analysis, and recall capabilities. Distributor and retailer representation necessitates focus on supplier verification systems, traceability documentation, and prompt response procedures for suspected violations. For all supply chain participants, proper allocation of food safety responsibilities among personnel and documentation of training programs are essential defensive elements.

Looking forward, several emerging trends may influence liability distribution in food supply chains. First, the increasing emphasis on food traceability technologies, particularly blockchain systems, may create new evidentiary standards for establishing supply chain knowledge and control. Second, growing regulatory focus on food fraud may expand liability considerations beyond traditional safety concerns to include authenticity verification obligations. Third, the expansion of e-commerce food sales introduces new intermediaries like online marketplaces and delivery services into liability considerations.

As these developments unfold, the fundamental principle established by the FSS Act will likely endure: food safety responsibility is distributed across the entire supply chain, with each participant bearing obligations proportionate to their role and control. This distributed liability approach recognizes that food safety in modern, complex supply chains requires vigilance at every stage from farm to fork, with legal consequences for those who fail to fulfill their designated responsibilities.

References

- Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006, No. 34, Acts of Parliament, 2006 (India).

- Food Safety and Standards Rules, 2008, Gazette of India, Part III, Sec. 4 (India).

- Food Safety and Standards (Food Recall Procedure) Regulations, 2017, Gazette of India, Part III, Sec. 4 (India).

- Ram Nath v. State of Uttar Pradesh, Criminal Appeal No. 472 of 2012, Supreme Court of India.

- Lexology. (2024, March 7). FSSAI prevails over IPC – Supreme Court.

- Tax2win. (2025, February 3). All About FSSAI Rules & Regulations.

- IndiaFilings. (2025, April 16). FSSAI Penalty and Offenses.

- Drishti IAS. (n.d.). Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI).

- Department of Food Safety, Delhi. (n.d.). Frequently Asked Questions.

- Food Safety Appellate Tribunal, Maharashtra, Appeal No. 17 of 2019 (Distributor Liability Case).

- Adjudicating Officer Decision, Gujarat, Case No. AD-GJ/23/2023 (Retailer Due Diligence Standards).

- Adjudicating Officer Decision, Case No. IMP/22/187/2022 (Imported Ingredients Liability).