Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

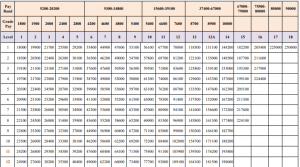

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

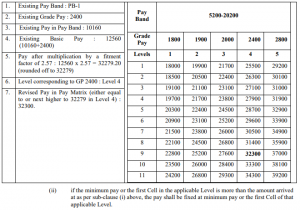

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

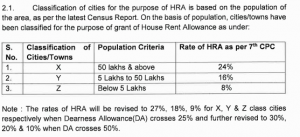

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

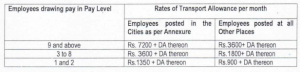

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Well-Known Trademarks in India: Enhanced Protection for Distinguished Brands

Introduction

The concept of “well-known trademarks” represents a cornerstone of intellectual property protection in India, offering heightened safeguards to marks that have achieved substantial recognition among consumers. Recent judgments by the Delhi High Court, including the 2025 PUMA SE vs. Mahesh Kumar case, have further solidified the special status these marks enjoy under Indian law. This article examines the legal framework surrounding well-known trademarks in India, the process of obtaining such status, and the enhanced protections they receive.

Legal Framework and Definition of Well-Known Trademarks

Well-known trademarks occupy a privileged position in India’s trademark jurisprudence. The Trade Marks Act, 1999, recognizes well-known marks as those that have acquired significant recognition within the relevant sector of the public, such that use of those marks by unauthorized entities would likely suggest a connection with the original proprietor. This special recognition extends protection beyond the specific goods or services for which the trademark is registered, allowing proprietors to prevent unauthorized use even in unrelated product categories.

The declaration of a trademark as “well-known” follows a procedure outlined in Rule 124 of the Trade Marks Rules, 2017. This involves filing a request with the Registrar of Trade Marks, who then invites objections from the general public by publishing the proposed well-known trademark in the Trade Marks Journal. If no valid objections are raised within the stipulated period, the trademark is officially declared well-known and included in the list maintained by the Trade Marks Registry.

In the recent PUMA SE case, the court noted that the plaintiff’s trademark ‘PUMA’ had been declared as a well-known trademark in India on December 30, 2019, by the Trade Marks Registry, which was published in the Trade Marks Journal bearing no. 1934. Additionally, during the course of the proceedings, PUMA’s marks ‘PUMA’ and ‘leaping cat device’ were also declared as well-known marks and published in Trade Marks Journal bearing no. 2144 dated February 19, 2024.

Enhanced Protection for Well-Known Trademarks

The special status granted to well-known trademarks provides their owners with significantly expanded protection compared to ordinary trademarks. This expanded protection stems from judicial recognition that well-known marks, having invested substantially in building brand reputation, require stronger safeguards against potential infringement and dilution.

The Delhi High Court in PUMA SE vs. Mahesh Kumar emphasized this principle, citing the Hamdard National Foundation case which established that “the requirement of protection varies inversely with the strength of the mark; the stronger the mark, the higher the requirement to protect the same”. This principle acknowledges that well-known marks face greater risk of exploitation precisely because of their market recognition and consumer association.

This heightened protection extends across all classes of goods and services, regardless of whether the original trademark owner operates in those sectors. The rationale behind this extended protection is to prevent dilution of the distinctive character of the well-known mark and to protect consumers from confusion regarding the source or origin of goods and services.

Counterfeiting and Well-Known Trademarks

Well-Known Trademarks in India, particularly those associated with luxury or premium brands, frequently become targets for counterfeiting activities. The Delhi High Court, in Louis Vuitton Malletier v. Capital General Store, characterized counterfeiting as “a commercial evil, which erodes brand value, amounts to duplicity with the trusting consumer, and, in the long run, has serious repercussions on the fabric of the national economy”.

Counterfeiters typically target well-known marks precisely because of their established market reputation and consumer trust. This exploitation not only dilutes the distinctive character of these marks but also misleads consumers regarding the authenticity and quality of the products they purchase. For luxury brands like PUMA and Louis Vuitton, counterfeiting represents a significant threat to their market position and brand integrity.

Judicial Approach to Well-Known Trademark Protection

Indian courts have consistently recognized the need for robust protection of well-known trademarks. The Delhi High Court’s approach in recent cases demonstrates a firm stance against infringement and counterfeiting of well-known marks, reflecting a judicial understanding of the commercial implications of such violations.

In the PUMA case, the court found that the defendant was manufacturing counterfeit products under PUMA’s registered and well-known marks. The court emphasized that well-known marks require a higher degree of protection as they are “highly susceptible to piracy”. This vulnerability stems from their market recognition, with stronger marks paradoxically facing greater risks of exploitation by those seeking to capitalize on their established reputation.

Similarly, in the Louis Vuitton case, the court observed that counterfeiters completely abandon “any right to equitable consideration by a Court functioning within the confines of the rule of law”. This characterization reflects the judiciary’s recognition of counterfeiting not merely as a private wrong against the trademark proprietor but as a broader commercial and social evil with widespread economic implications.

Remedies and Enforcement

The enhanced protection for well-known trademarks is reflected in the remedies available to their proprietors. Courts have shown willingness to grant substantial relief in cases involving infringement of well-known marks, including permanent injunctions, damages, and costs.

In the PUMA case, the Delhi High Court granted a permanent injunction restraining the defendant from manufacturing and selling counterfeit PUMA products. Additionally, the court awarded costs of Rs. 9,00,000 along with damages of Rs. 2,00,000, recognizing this as “a befitting case for grant of actual costs on account of a clear case being made out for counterfeiting”.

Similarly, in the Louis Vuitton case, the court directed the defendant to pay Rs. 5 lakhs to the plaintiff within four weeks, failing which the proprietor would face imprisonment in civil prison. This stringent approach reflects the court’s determination to create effective deterrents against trademark infringement and counterfeiting.

Conclusion

The concept of Well-Known Trademarks in India represents a sophisticated development in intellectual property jurisprudence, recognizing that certain marks transcend their specific product categories to achieve broader market recognition. Indian law, both through statutory provisions and judicial interpretation, has established a robust framework for protecting these distinguished marks.

Recent cases involving PUMA and Louis Vuitton demonstrate the judiciary’s commitment to enforcing this enhanced protection, particularly against the growing threat of counterfeiting. As well-known marks continue to face exploitation in an increasingly globalized marketplace, the legal framework surrounding their protection remains essential to maintaining brand integrity and consumer trust.

The recognition of a trademark as “well-known” thus serves not merely as an acknowledgment of its market prominence but as a gateway to enhanced legal protection commensurate with its commercial significance. For brand owners, securing this status represents a valuable tool in their broader intellectual property protection strategy, particularly in combating infringement and counterfeiting across diverse product categories.

Trademark Protection in India: Understanding the PUMA Trademark Infringement Judgment and Legal Framework for Combating Counterfeiting

Introduction

The Delhi High Court’s recent judgment in PUMA SE vs. Mahesh Kumar represents a significant development in India’s trademark jurisprudence, particularly in the realm of counterfeit goods. This comprehensive 2025 decision not only reinforces the protection afforded to well-known trademarks but also elucidates the judicial approach to counterfeiting as a commercial evil. Through PUMA trademark infringement case, we gain valuable insights into India’s evolving trademark protection framework and its alignment with global intellectual property standards.

Understanding Trademarks and Their Fundamental Concepts

Trademarks serve as vital commercial identifiers in today’s marketplace, representing significant business assets that embody years of reputation and consumer trust. A trademark encompasses any word, name, symbol or device utilized to recognize and set apart goods and/or services from those of others. These unique identifiers extend beyond conventional elements to include logos, scents, sounds, personal brand names, slogans, fragrances, and even specific colors associated with particular brands.

The essential function of a trademark is “to exclusively identify the commercial source or origin of products or services, such that a trademark, properly called, indicates source or serves as a badge of origin”. This function highlights the trademark’s role as a distinguishing mechanism that enables consumers to differentiate between competing products in the marketplace. As search result accurately notes, marketing of a particular good or service by the producer is much better off as by trademark because recognition becomes easier and quality is assured.

Trademarks also serve as guarantees of consistent quality. When consumers encounter a particular trademark, they form expectations based on prior experiences with products bearing that mark. This quality assurance function creates a reciprocal relationship between trademark owners and consumers, wherein businesses are incentivized to maintain consistent quality to preserve their trademark’s value and reputation.

Evolution of Trademark Law in India

The development of trademark law in India represents a gradual transition from common law principles to a comprehensive statutory framework. Before 1940, trademark protection in India was primarily grounded in common law principles of passing off and equity, following the English legal tradition. This period was characterized by the absence of formal registration systems, with trademark disputes resolved through judicial interpretations of unfair competition principles.

The first statutory framework for trademarks emerged with the Trade Marks Act, 1940, which mirrored provisions found in the UK Trade Marks Act of 1938. This legislation was superseded by the Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, 1958, which consolidated trademark-related provisions previously scattered across various statutes including the Indian Penal Code, Criminal Procedure Code, and the Sea Customs Act.

The current governing legislation, the Trade Marks Act, 1999, represents India’s commitment to aligning its intellectual property framework with international standards, particularly those established by the TRIPS Agreement. This modern legislation introduced several significant innovations, including the registration of service marks, the filing of multiclass applications, the extension of the period of registration of a trade mark to ten years, and the recognition of the idea of well-known marks.

The Trade Marks Act, 1999: Key Provisions and Protections

The Trade Marks Act, 1999 provides a robust framework for trademark protection in India, defining a “mark” under Section 2(1)(i)(V)(m) as encompassing “devices, brands, headings, labels, tickets, names, signatures, words, letters, and numerals”. The Act adopts a comprehensive approach to trademark protection, addressing both registered and unregistered marks.

Section 28 of the Act confers exclusive rights on registered trademark owners, empowering them to prevent unauthorized use of identical or deceptively similar marks. According to Section 29(1), a trademark is infringed when a person who is not the proprietor or authorized by the proprietor uses a mark identical or deceptively similar to the registered trademark.

The concept of “well-known trademarks” represents one of the Act’s most significant features. As defined in the legislation, a well-known trademark is “a mark in relation to any goods and services which has become so to the substantial segment which uses such goods or receives such services that the use of such mark in relation to other goods or services would be likely to be taken as indicating a connection in course of trade”. This provision affords enhanced protection to marks that have attained substantial recognition.

The PUMA Trademark Infringement Case: Analysis of Delhi High Court’s Landmark Judgment

The recent Delhi High Court judgment in PUMA SE vs. Mahesh Kumar (February 2025) offers valuable insights into judicial approaches to trademark protection, particularly concerning well-known marks. The case concerned the unauthorized manufacture and sale of counterfeit PUMA-branded footwear, with the plaintiff seeking permanent injunction against the defendant’s infringing activities.

PUMA SE, one of the world’s largest sports brands, has a long-established history dating back to 1948, with trademark registrations in India since 1977. Significantly, the Court noted that “the plaintiff’s trademark ‘PUMA’ has been declared as a well-known trademark in India on 30th December, 2019, by the Trade Marks Registry which was published in the Trade Marks Journal bearing no. 1934”. This recognition confers enhanced protection, acknowledging the mark’s distinctive character and substantial recognition among consumers.

The Court’s findings regarding the defendant’s activities were unequivocal. Based on the Local Commissioner’s report, the Court observed that:

“The defendant is manufacturing counterfeit products under the plaintiff’s registered and well-known marks, ‘PUMA’, PUMA logo and Form strip logo. Further, counterfeit products of other known brands as well are found, i.e. Adidas, Nike etc.”

This observation highlights the systematic nature of the defendant’s counterfeiting operation, extending beyond the plaintiff’s marks to encompass other well-known brands. The evidence revealed not just the sale of counterfeit products but the manufacturing infrastructure designed to facilitate widespread counterfeiting activities.

Counterfeiting vs. Trademark Infringement: Legal Distinctions

A critical aspect of trademark jurisprudence clarified in the PUMA judgment is the distinction between counterfeiting and trademark infringement. While related concepts, they involve different legal standards and remedies. As aptly summarized in search result: “All counterfeits are infringements but all infringements are not counterfeits.”

Trademark infringement occurs when a person who is not the proprietor or authorized by the proprietor uses a mark identical or deceptively similar to the registered trademark. Counterfeiting, however, represents a more egregious violation, involving “an imitation of the original goods in order to provide goods of cheaper quality, to deceive the consumers and to harm the goodwill of the original Trademark owner”.

The legal classification and burden of proof also differ significantly between these concepts:

“A Trademark infringement is usually a civil wrong and the punishment for the same is provided in the Trademark Act, 1999. Counterfeit is a criminal offence and the punishment is provided in the Indian Penal Code. The burden of proof in case of Trademark infringement lies on the plaintiff to prove that the defendant has used the Trademark unauthorised. Whereas, in counterfeit, the mere existence of an identical imitation is a proof enough.”

This distinction informs the Court’s approach to remedies, with counterfeiting inviting more severe sanctions given its criminal nature and intent to deceive.

Judicial Perspective on Counterfeiting: The Commercial Evil

The Delhi High Court’s pronouncements on counterfeiting in the PUMA trademark infringement judgment reflect a firm judicial stance against this practice. Drawing from earlier jurisprudence, particularly the Louis Vuitton Malletier vs. Capital General Store case (2023), the Court emphasized the profound commercial and social implications of counterfeiting:

“Counterfeiting is an extremely serious matter, the ramifications of which extend far beyond the confines of the small shop of the petty counterfeiter. It is a commercial evil, which erodes brand value, amounts to duplicity with the trusting consumer, and, in the long run, has serious repercussions on the fabric of the national economy. A counterfeiter abandons, completely, any right to equitable consideration by a Court functioning within the confines of the rule of law. He is entitled to no sympathy, as he practices, knowingly and with complete impunity, falsehood and deception.”

This characterization of counterfeiting as a “commercial evil” underscores its multifaceted harm—to brand owners through the dilution of intellectual property rights, to consumers through deception regarding product quality and origin, and to the broader economy through the undermining of legitimate business practices.

The Court further emphasized that well-known marks like PUMA require enhanced protection:

“It is settled law that a mark which is well-known requires a higher degree of protection, as it is highly susceptible to piracy. Thus, the Division Bench of this Court in the case of Hamdard National Foundation (India) and Another Versus Sadar Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., 2022 SCC OnLine Del 4523, held as follows: ‘…the requirement of protection varies inversely with the strength of the mark; the stronger the mark, the higher the requirement to protect the same.'”

Remedies and Damages in Trademark Infringement Cases

The PUMA judgment illustrates the comprehensive remedial approach available in trademark infringement cases. The Court granted a permanent injunction restraining the defendant from manufacturing, selling, or offering for sale any products bearing PUMA’s registered trademarks. This injunctive relief represents the primary mechanism for preventing ongoing harm to the trademark owner’s rights.

Additionally, the Court awarded substantial damages and costs:

“In view of the above, the Court was of the view that PUMA was entitled to actual costs as well as damages. It thus awarded Rs. 9 lakh costs along with Rs. 2 lakh damages to PUMA.”

This award reflects the Court’s recognition of both the actual financial loss suffered by PUMA and the need for deterrence against future infringement. The Court specifically noted that “the present is befitting case for grant of actual costs on account of a clear case being made out for counterfeiting against the defendant”.

The remedial framework extends beyond financial compensation. In cases of counterfeiting, courts may also order the destruction of infringing goods and the disclosure of supplier and distribution information. As noted in the Nike Innovate C.V v. Ashok Kumar case, “an aggrieved party, in case of counterfeit can seek for damages, destruction of the counterfeit goods, injunction and accounts of profits”.

Protection of Well-Known Trademarks in India

The PUMA case highlights India’s robust protection for well-known trademarks, recognizing their enhanced vulnerability to exploitation. The Trade Marks Act, 1999 specifically acknowledges well-known marks, defined as those that have gained substantial recognition within relevant consumer segments.

PUMA’s trademarks, including the word mark “PUMA” and the distinctive leaping cat logo, have been officially recognized as well-known marks in India. The Court noted:

“During the course of the present proceedings, the plaintiff’s marks ‘PUMA’ and ‘leaping cat device’ have also been declared as well-known marks and published in Trade Marks Journal bearing no. 2144 dated 19th February, 2024 at Sr. Nos. 68 and 69 respectively.”

This designation affords PUMA’s marks protection beyond the specific goods for which they are registered, acknowledging their distinctive character and reputation among consumers. The enhanced protection recognizes that unauthorized use of well-known marks on unrelated products can dilute their distinctiveness and damage the original owner’s reputation.

The Court cited precedent establishing that “in case of a well-known mark, which has acquired a high degree of goodwill, the mark requires higher protection as it is more likely to be subjected to piracy from those who seek to draw an undue advantage of its goodwill”1. This principle acknowledges the proportional relationship between a mark’s strength and its vulnerability to exploitation, necessitating correspondingly robust protection.

E-Commerce Platforms and Trademark Infringement

While not directly addressed in the PUMA judgment, related cases highlight the emerging challenges of trademark infringement in e-commerce contexts. The Delhi High Court recently addressed this issue in a case involving PUMA and the e-commerce platform IndiaMART, establishing important principles regarding intermediary liability.

The Court held that e-commerce platforms cannot claim safe harbor protections while facilitating the sale of counterfeit goods. Justice C. Hari Shankar observed:

“E-commerce websites are commercial ventures, and are inherently profit oriented. There is, of course, nothing objectionable in this; but, while ensuring their highest returns, such websites have also to sedulously protect intellectual property rights of others. They cannot, with a view to further their financial gains, put in place a protocol by which infringers and counterfeiters are provided an avenue to infringe and counterfeit.”

This ruling establishes important precedent regarding the responsibilities of online marketplaces in preventing trademark infringement, extending the protective framework beyond traditional retail contexts.

Conclusion: Strengthening India’s Intellectual Property Framework

The PUMA judgment represents a significant contribution to India’s evolving trademark jurisprudence, reinforcing protection for well-known marks while establishing clear principles regarding counterfeiting. The Court’s characterization of counterfeiting as a “commercial evil” with far-reaching economic implications reflects a sophisticated understanding of intellectual property’s role in modern commerce.

The judgment aligns with international trends in intellectual property protection, demonstrating India’s commitment to maintaining robust safeguards for trademark owners while balancing broader commercial and consumer interests. The substantial damages and costs awarded to PUMA signal to potential infringers that counterfeiting activities will face significant legal and financial consequences.

As global commerce continues to evolve, particularly in digital contexts, the principles established in cases like PUMA SE vs. Mahesh Kumar provide essential guidance for navigating complex questions of trademark protection. The recognition of well-known marks’ enhanced vulnerability to exploitation and the corresponding need for strengthened protection represent important developments in India’s intellectual property framework.

Through decisions like the PUMA judgment, India’s courts continue to refine and strengthen trademark protection, ensuring that the country’s intellectual property regime supports innovation, respects established brand equity, and maintains consumer confidence in the authenticity and quality of branded products.

Harmonizing Urban Development: A Comprehensive Analysis of Gujarat’s Town Planning Framework

Introduction

Gujarat’s approach to urban planning represents one of India’s most sophisticated frameworks, integrating long-term vision with practical implementation mechanisms. At its core is the Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development Act, 1976 (GTPUDA), which creates a three-tiered system comprising Development Plans, Gujarat’s town planning Schemes, and General Development Control Regulations. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how these components function in synergy, supported by evolving jurisprudence that ensures coherent implementation.

Understanding the Legislative of Gujarat’s Town Planning Framework

The Genesis and Purpose of GTPUDA

The GTPUDA emerged from the need to systematize urban growth in Gujarat’s rapidly expanding cities. Its primary objective is to ensure planned development through a framework that balances public infrastructure needs with private property rights. Prior to this Act, urban development was often haphazard, with inadequate infrastructure and insufficient public spaces.

The Act establishes Urban Development Authorities (UDAs) and Area Development Authorities (ADAs) under Section 5 and Section 6 respectively, empowering them to prepare and implement development plans. These authorities serve as the institutional backbone for urban planning in Gujarat.

Three Pillars of Gujarat’s Town Planning

- Development Plan (DP): The macro-level blueprint providing a 20-25 year vision for land use, zoning, and infrastructure development.

- Town Planning Scheme (TPS): The micro-level implementation mechanism that reconstitutes land parcels to create infrastructure while ensuring equitable distribution of development benefits.

- General Development Control Regulations (GDCR): Technical rules governing construction parameters, land use compatibility, and building standards.

This three-tiered approach creates a comprehensive planning framework that operates at different scales but maintains internal consistency.

Development Plan: The Master Blueprint

Legal Definition and Statutory Basis

According to Section 2(10) of GTPUDA, a Development Plan means “a plan for the development or redevelopment of the area within the jurisdiction of an Authority.” The preparation process is outlined in Sections 9-19 of the Act.

Preparation Process and Contents

The preparation follows a structured process:

- Declaration of Intention (Section 9): The Authority publishes its intention to prepare a Development Plan.

- Draft Development Plan (Section 10): Within 3 years, a draft plan is prepared containing:

- Proposed land uses (residential, commercial, industrial, recreational)

- Road networks and transportation systems

- Reservations for public purposes (schools, hospitals, parks)

- Zoning regulations and development control

- Public Participation (Section 13-15): The draft is published for objections and suggestions from citizens, fostering participatory planning.

- Consideration of Objections (Section 16): A committee addresses public input before finalizing the plan.

- State Government Sanction (Section 17): The final Development Plan becomes legally binding after state approval.

- Revision (Section 18-19): Periodic revisions ensure relevance to changing urban needs.

Judicial Interpretations on Development Plans

In Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation v. Ahmedabad Green Belt Khedut Mandal (2014), the Supreme Court held that Development Plans must respect constitutional rights to property while serving public interest. The court emphasized that arbitrary zone changes without technical justification are impermissible.

Similarly, in Reliance Industries Ltd. v. State of Gujarat & Ors. (2017), the Gujarat High Court ruled that Development Plans cannot be modified capriciously and must follow the same rigorous process as their original formulation.

Town Planning Scheme: The Implementation Mechanism

Definition and Purpose

Section 2(25) defines a Town Planning Scheme as “a scheme whereby the pattern of an area is improved by the development of land and by the construction, alteration, or removal of buildings thereon.”

TPS operates through the principle of land pooling and reconstitution, where irregular land parcels are pooled, infrastructure is planned, and final plots are returned to owners proportionate to their original holdings.

Stages of Town Planning Scheme

| Stage | Legal Provision | Key Actions | Timeframe | Authority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Declaration of Intention | Section 40 | Publication of intent to prepare TPS | Initial step | Local Authority |

| Draft Scheme | Section 41-47 | Preparation and publication of draft scheme | Within 12 months of declaration | Local Authority |

| Objection Period | Section 48 | Inviting and addressing public objections | 1 month from publication | Local Authority |

| Sanction of Draft Scheme | Section 48(2) | State Government approves draft scheme | After addressing objections | State Government |

| Appointment of TPO | Section 50 | Appointment of Town Planning Officer | After sanction of draft scheme | State Government |

| Preliminary Scheme | Section 52 | TPO prepares preliminary scheme after hearings | Within 12 months of appointment | Town Planning Officer |

| Final Scheme | Section 65 | Final scheme prepared and submitted | After addressing appeals | State Government |

| Implementation | Section 66-67 | Execution of scheme provisions | After final sanction | Local Authority |

Key Features of Town Planning Schemes

- Land Reconstitution (Section 45): Original plots are reconstituted into final plots after deducting land for:

- Roads and infrastructure (typically 20-30%)

- Social amenities like parks, schools (15-20%)

- Sale to fund the scheme (5-10%)

- Incremental Contribution (Section 67): Landowners contribute proportionately to infrastructure costs based on the increase in land value.

- Compensation Mechanism (Section 67): Landowners receive compensation for:

- Difference between original and final plot values

- Structures demolished during implementation

- Temporary displacement costs

Judicial Precedents on Town Planning Schemes

In Mrugendra Indravadan Mehta v. Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (2024), the Supreme Court reaffirmed that Town Planning Schemes must be interpreted as a complete code, ensuring that variations under Sections 70 and 71 must be harmonized to maintain procedural consistency.

The Gujarat High Court in Sultanbhai Jamalbhai Mansuri vs. State of Gujarat (2022) emphasized that objections filed under Rule 26(3) must be considered by the Town Planning Officer before the scheme’s sanctioning.

Notably, in Manekbai Kanji v. New Ahmedabad Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (1972), the court established that TPS provisions override private agreements concerning land use once the scheme is sanctioned.

General Development Control Regulations: Technical Framework

Legal Basis and Purpose

The GDCR derives its authority from Section 116A of GTPUDA, which empowers the State Government to frame regulations for controlling development. The current Gujarat GDCR 2017 provides comprehensive technical parameters for construction and land use.

Key Provisions of GDCR 2017

- Floor Space Index (FSI) Regulations:

- Rule 7.1 specifically addresses FSI calculation for plots divided by roads: “When a plot is affected by road line/road widening or reservation, FSI shall be permissible on the original plot area. The owner shall handover the affected area to the appropriate authority free of cost in lieu of FSI on said affected area.”

- This means that even if a road divides an original plot into multiple final plots, the FSI is calculated based on the entire original plot area.

- Unified Treatment of Divided Plots:

- Rule 4.3 mandates that: “If a plot is divided into two or more parts due to road planning or any infrastructure, all divided parts shall be treated as one plot for development purposes including FSI calculation.”

- This ensures landowners aren’t penalized through reduced development rights when roads are introduced through their plots.

- Zoning Compliance:

- Rule 12.1-12.5 stipulates that all construction must comply with the zone designated in the Development Plan.

- Different permissible uses (residential, commercial, industrial) have specific development controls.

Case Study: Rajkot Final Plot No. 236

In the landmark case concerning Rajkot Final Plot No. 236 (Kantilal Manilal Patel v. Rajkot Municipal Corporation, 2019), the Gujarat High Court addressed the issue of a road dividing an original plot:

- The petitioner owned a large plot that was divided by a proposed 12-meter road.

- The TPO had allocated two separate final plots (236/1 and 236/2) on either side of the road.

- The petitioner challenged this division, arguing that it reduced development potential.

- The Court ruled that:

- Under GDCR Rule 7.1, FSI must be calculated on the entire original plot area.

- The landowner should be permitted to utilize the combined FSI across both final plots.

- The authority must consider both plots as a single entity for development permission purposes.

This judgment reinforced the principle that GDCR provisions must be interpreted to maximize development rights when infrastructure necessitates plot division.

Synergy Between Development Plan, TPS, and GDCR

Hierarchical Relationship

The three components operate in a hierarchical relationship:

- Development Plan: Establishes the macro-level vision and zoning.

- Town Planning Scheme: Implements the DP vision through land reconstitution.

- GDCR: Provides technical parameters for actual construction.

This relationship is legally enforced through Section 40(3) of GTPUDA, which mandates that Town Planning Schemes must conform to the Development Plan. Similarly, Rule 3.1 of GDCR stipulates that all development permissions must comply with both the Development Plan and applicable Town Planning Schemes.

Practical Implementation Harmony

When functioning properly, these three components work in tandem:

- The Development Plan designates a commercial corridor along a major road.

- The Town Planning Scheme reconstitutes irregular agricultural plots into regularly shaped commercial plots with proper road access.

- The GDCR determines permissible height, FSI, and setbacks for commercial buildings on these plots.

Resolving Conflicts Between Components

Courts have established clear principles for resolving conflicts:

- Primacy of Development Plan: In Babubhai & Co. v. State of Gujarat (2016), the High Court ruled that TPS provisions cannot override DP reservations.

- Self-Contained Code: The Supreme Court in Jayesh Dhanesh Goragandhi v. Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (2012) established that TP Schemes function as a “self-contained code,” overriding conflicting provisions in other legislation.

- Equitable Interpretation: In Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority v. Sharadkumar Jayantilal Panchal (2016), the court mandated that GDCR provisions must be interpreted to maximize utility while maintaining public purpose.

Comprehensive Judicial Framework

Principle of Harmonious Construction

Courts have consistently held that GTPUDA’s provisions must be read holistically:

- No Provision in Isolation: In Reliance Industries Ltd. v. Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation (2013), the Supreme Court emphasized that no provision of GTPUDA can be read in isolation from other provisions.

- Scheme as a Whole: The Gujarat High Court in Piyush N. Patel v. State of Gujarat (2018) ruled that objections to TPS must be considered in light of the scheme’s overall objectives, not merely technical compliance.

- Purpose-Oriented Interpretation: In Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation v. Hathising Manufacturing Co. (2011), the court mandated that technical defects in procedure do not invalidate a scheme if its substantive purpose is achieved.

Landmark Judgments Shaping Gujarat’s Town Planning Jurisprudence

- Balance Between Public and Private Interests:

- Jamnadas Prabhudas v. State of Gujarat (1976): Established that land reconstitution must balance infrastructure needs with private property rights.

- Narandas Karsandas v. S.A. Kamdar (1977): Recognized that temporary diminution of property rights is permissible for long-term planning benefits.

- Procedural Safeguards:

- Sulochana Ben v. State of Gujarat (2014): Held that failure to consider objections renders a scheme legally flawed.

- Chirag Construction v. Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (2017): Established timeline requirements for processing objections.

- Integration of Planning Components:

- Builders Association of India v. State of Gujarat (2013): Ruled that GDCR amendments must align with Development Plan objectives.

- Ahmedabad Study Action Group v. State of Gujarat (1997): Emphasized the need for environmental considerations in all planning components.

Practical Implications for Stakeholders

For Landowners and Developers

- Rights Under the Act:

- Right to object to Draft DP/TPS under Sections 15 and 47

- Right to proportionate reconstitution under Section 45

- Right to compensation for acquired land under Section 67

- Strategic Considerations:

- Monitor gazette notifications for planning intentions

- Submit timely, well-reasoned objections

- Understand GDCR provisions to maximize development potential

- Seek unified treatment of plots divided by infrastructure

- Common Issues and Remedies:

- For excessive deductions, cite Section 45 proportionality principles

- For divided plots, invoke GDCR Rule 7.1 for unified FSI calculation

- For delayed implementation, seek remedies under Section 69

For Planning Authorities

- Statutory Obligations:

- Ensure Development Plan-TPS-GDCR consistency

- Consider all objections under Sections 16 and 47

- Follow prescribed timelines for plan preparation

- Best Practices:

- Conduct thorough surveys before plan preparation

- Ensure transparent public participation

- Provide detailed reasoning for accepting/rejecting objections

- Maintain proper records of all planning decisions

Conclusion: The Future of Gujarat’s Town Planning Framework

Gujarat’s town planning framework represents a sophisticated system that balances macro-vision with micro-implementation. The synergy between Development Plans, Town Planning Schemes, and GDCR has made Gujarat a model for urban development in India.

Recent judicial interventions have further strengthened this framework by emphasizing several key principles:

- No provision of the Act can operate in isolation.

- Planning instruments must be interpreted to maximize both public benefit and private development rights.

- Procedural safeguards must be respected to ensure equitable outcomes.

The success of Gujarat’s town planning framework has been evident in cities like Ahmedabad, where TPS mechanisms have created well-planned areas with adequate infrastructure. However, challenges remain, particularly in implementation timelines and addressing emerging urban issues like climate resilience and affordable housing.

Future reforms should focus on:

- Streamlining approval processes

- Incorporating digital technologies for planning and monitoring

- Enhancing climate-responsive planning provisions

- Strengthening mechanisms for inclusionary development

The enduring principle that provisions of town planning law cannot operate in isolation but must function harmoniously continues to guide both legislative amendments and judicial interpretations, ensuring that Gujarat’s urban areas develop in a planned, equitable, and sustainable manner.

Jal Hi Amrit: Legal Mechanisms for Water Conservation in India

Introduction

Water, often referred to as the elixir of life, is a fundamental resource that sustains all forms of life on Earth. The ancient Sanskrit phrase “Jal Hi Amrit” (Water is Nectar) encapsulates the intrinsic value of water as an indispensable element of life, culture, and civilization. In contemporary times, however, the rapid pace of industrialization, urbanization, and climate change has rendered water conservation an urgent global necessity. Legal frameworks, both national and international, serve as critical tools in ensuring the sustainable management and preservation of this invaluable resource. This article delves deeply into the intricate web of legal mechanisms, policies, regulations, and judicial pronouncements governing water conservation, with a focus on India and its integration into global efforts.

The Critical Importance of Water Conservation

Water conservation has become a paramount concern in the 21st century due to escalating pressures from population growth, industrial demands, and environmental degradation. In India, the situation is particularly acute, given that the country supports approximately 18% of the global population with only 4% of the world’s freshwater resources. The demand-supply gap continues to widen, exacerbated by over-extraction, contamination, and wastage. Rivers, lakes, and groundwater sources—the primary reservoirs of fresh water—are under significant threat from pollution and unsustainable practices. Effective legal mechanisms are thus indispensable to address these challenges and ensure equitable access to clean water for all.

Legal Framework for Water Conservation in India

India’s approach to water conservation is underpinned by a combination of constitutional mandates, statutory provisions, administrative guidelines, and judicial activism. Despite water being classified as a state subject under the Indian Constitution, the central government plays a pivotal role in formulating national policies and guidelines to address water-related concerns.

Constitutional Provisions

The Constitution of India provides a strong foundation for water conservation through its various provisions. Article 48A of the Directive Principles of State Policy enjoins the state to protect and improve the environment, including water bodies. Article 51A(g) imposes a fundamental duty on every citizen to safeguard the natural environment, encompassing rivers, lakes, and other water resources. These provisions, although non-justiciable in nature, serve as guiding principles for the formulation of environmental and water conservation laws.

The division of legislative powers between the Centre and states under the Seventh Schedule further shapes water governance. While water is primarily a state subject, subjects such as environmental protection and inter-state river disputes fall within the concurrent and union lists, respectively. This distribution has led to a complex interplay of jurisdictional powers, necessitating cooperative federalism for effective water management.

Statutory Laws and Policies

India has enacted several statutes to regulate water use, prevent pollution, and promote conservation. These laws address diverse aspects of water management and reflect the evolving understanding of sustainability.

One of the most significant pieces of legislation is the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974. This act was the first comprehensive legal measure aimed at combating water pollution. It established the Central and State Pollution Control Boards, which are vested with the authority to set water quality standards, monitor pollution levels, and take punitive action against violators. The Act’s provisions underscore the importance of maintaining the wholesomeness of water for human consumption and ecological balance.

Complementing this is the Environment Protection Act of 1986, a wide-ranging statute that empowers the central government to regulate activities that harm water bodies. This Act serves as an umbrella framework for various environmental laws and has been instrumental in regulating industrial discharge, hazardous waste, and other pollutants that contaminate water sources.

The Indian Easements Act, 1882, though a colonial-era law, continues to govern groundwater extraction. It recognizes the right of landowners to use water beneath their land, subject to reasonable and sustainable usage. However, unregulated extraction under this law has led to significant depletion of groundwater levels, prompting states like Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu to enact specific groundwater management laws. These state-level legislations often mandate permissions for groundwater extraction and promote practices such as rainwater harvesting.

The National Water Policy, first formulated in 1987 and revised in 2002 and 2012, provides a strategic vision for water management in India. The policy emphasizes the need for integrated water resource management, equitable distribution, and the importance of conservation measures such as recycling, reuse, and artificial recharge of aquifers. It also stresses the need to treat water as a public resource rather than a private commodity.

The River Boards Act, 1956, aims to regulate the development and management of inter-state rivers and river valleys. Although its implementation has been limited, the Act reflects the intent to foster cooperation between states in the management of shared water resources.

Judicial Interventions

The Indian judiciary has played a transformative role in advancing water conservation. Courts have expansively interpreted the fundamental right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution to include the right to clean and safe water. Landmark judicial pronouncements have not only reinforced the responsibility of the state and individuals but have also laid the groundwork for progressive policies.

In MC Mehta v. Union of India (1987), the Supreme Court unequivocally declared that the right to clean water is an essential part of the right to life. The case dealt with the pollution of the Ganga River and led to significant directives for the establishment of treatment plants and pollution control measures.

Similarly, in Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar (1991), the court reiterated that access to clean drinking water is a fundamental right. This case emphasized the need for stringent enforcement of pollution control laws to protect water resources.

Another noteworthy case, Narmada Bachao Andolan v. Union of India (2000), addressed the environmental and social impacts of the Sardar Sarovar Project. While the court upheld the construction of the dam, it underscored the importance of balancing developmental needs with ecological sustainability.

In Alaknanda Hydro Power Co. Ltd. v. Anuj Joshi (2014), the Supreme Court emphasized the need for cumulative environmental impact assessments of hydroelectric projects in fragile ecosystems. This judgment highlighted the interdependence of water conservation and environmental protection.

International Legal Frameworks for Water Conservation

Water conservation is a global concern, and international legal frameworks play a vital role in promoting sustainable practices. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) aims to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. The global community has adopted several treaties and conventions, such as the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, which focuses on the conservation of wetlands, crucial for maintaining hydrological and ecological balance.

In the United States, the Clean Water Act (1972) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974) provide comprehensive legal frameworks for protecting water quality and ensuring safe drinking water. These laws mandate collaborative efforts between federal and state governments to regulate pollution and manage water resources sustainably.

The European Union’s Water Framework Directive (2000) sets ambitious targets for achieving “good status” for all water bodies by promoting integrated water resource management and pollution control. South Africa’s National Water Act (1998) stands out as a model law that treats water as a public resource, prioritizes equitable access, and emphasizes sustainability.

Challenges and the Way Forward

Despite a robust legal framework, India faces significant challenges in water conservation. Enforcement remains a critical bottleneck, with laws often failing to translate into effective action on the ground. The fragmentation of water governance across multiple agencies leads to inefficiencies and overlaps.

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-pronged approach. Strengthening institutional capacities, fostering inter-agency coordination, and ensuring strict enforcement of existing laws are crucial steps. Public awareness and community participation must be prioritized, as collective action is essential for sustainable water management.

Innovation and technology can also play a transformative role. The adoption of IoT and AI for monitoring water usage, detecting leaks, and predicting shortages can enhance efficiency. Integrating traditional water conservation systems, such as stepwells and tank irrigation, with modern techniques offers sustainable solutions.

International collaboration and knowledge-sharing can further enrich India’s water conservation efforts. By learning from global best practices, India can adopt more effective strategies for managing its precious water resources.

Conclusion

“Jal Hi Amrit” embodies the essence of water as a life-sustaining force that must be cherished and conserved. The intricate web of constitutional mandates, statutory laws, and judicial interventions underscores the critical role of legal mechanisms in ensuring water sustainability. However, laws alone are insufficient. Collective responsibility, technological innovation, and community engagement are equally important in creating a water-secure future. By recognizing water as a shared resource and a collective heritage, India can pave the way for a resilient and sustainable tomorrow.