Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

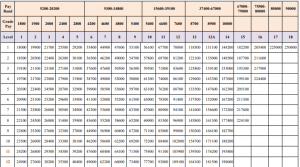

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

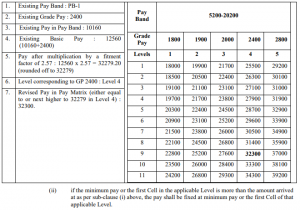

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

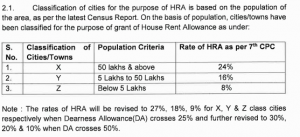

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

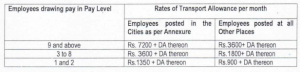

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Legal Implications of the Proposed Amendments to India’s Voting System

Introduction

The concept of democracy, as envisioned by the framers of the Indian Constitution, places the citizen at the center of governance, ensuring that the power of decision-making rests with the people through periodic elections. India’s electoral process, governed by the Representation of the People Act, 1951, and overseen by the Election Commission of India (ECI), is an embodiment of this democratic ideal. However, with the dynamic evolution of society and technology, the voting system in India faces significant challenges, prompting discussions on proposed amendments aimed at enhancing its efficacy, inclusivity, and integrity. This article explores the implications of the proposed amendments to India’s voting system, analyzing the regulatory framework, relevant laws, and landmark judicial pronouncements, while also addressing the broader socio-political impacts of these reforms.

Current Legal Framework Governing Voting in India

India’s voting system operates under a robust legal framework that ensures free, fair, and periodic elections. The Constitution of India, under Article 324, empowers the Election Commission to supervise, direct, and control the electoral process. Key legislative instruments include the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (primarily dealing with the preparation of electoral rolls), and the Representation of the People Act, 1951, which regulates the actual conduct of elections. Together, these laws aim to provide a transparent and accountable mechanism for the exercise of franchise.

The voting process itself is guided by the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961, which outlines the procedural aspects of conducting elections. With the introduction of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) in the late 20th century, the efficiency and security of the voting process were significantly enhanced. Legal safeguards exist to address malpractices such as booth capturing, impersonation, and undue influence under Sections 125 to 136 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. However, despite these provisions, contemporary challenges such as urban voter apathy, security concerns, technological vulnerabilities, and the disenfranchisement of internal migrants highlight the need for reform.

Proposed Amendments to India’s Voting System

The proposed amendments to India’s voting system focus on integrating technology, enhancing transparency, and increasing voter accessibility. Key proposals include the introduction of remote voting for migrant workers, the linkage of voter IDs with Aadhaar to curb duplication and fraud, and the potential use of blockchain technology for secure and tamper-proof voting.

Remote voting for migrant workers has emerged as a pivotal reform to address disenfranchisement. According to a 2017 Economic Survey, over 45 crore Indians are internal migrants, many of whom face logistical and administrative barriers to exercising their voting rights. The Election Commission has proposed piloting a remote voting system using blockchain technology. This system would allow registered voters to cast their vote from locations outside their home constituencies. The implementation of such a system would necessitate significant amendments to the Representation of the People Act, 1951, and the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961, to incorporate provisions for remote and technologically assisted voting mechanisms.

The proposal to link voter IDs with Aadhaar is another critical reform aimed at eliminating duplicate and fake entries in electoral rolls. This initiative, backed by Section 23(4) of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (introduced through the Election Laws (Amendment) Act, 2021), seeks to strengthen the integrity of voter lists. However, the proposal has sparked debates over privacy concerns, data security, and the potential exclusion of vulnerable populations, including the homeless and tribal communities, who may lack Aadhaar registration. Critics argue that the linkage, if implemented without adequate safeguards, could lead to the disenfranchisement of these groups, undermining the democratic principle of universal adult suffrage.

Blockchain-based voting has been heralded as a transformative step toward ensuring the integrity of elections. By creating an immutable and transparent ledger, blockchain technology can address concerns of tampering and manipulation. However, its implementation would require a comprehensive legal framework to address issues of accessibility, cybersecurity, and verifiability. Questions about digital literacy, equitable access to technology, and the reliability of blockchain networks in a diverse and populous country like India remain significant hurdles to its adoption.

Legal and Constitutional Challenges of Electoral Reforms

The proposed amendments to India’s voting system face significant constitutional and legal hurdles. The linkage of voter IDs with Aadhaar raises questions about the right to privacy, a fundamental right under Article 21 as upheld in the landmark judgment of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017). In this case, the Supreme Court emphasized the need for proportionality and necessity in implementing measures that infringe on privacy. Critics argue that mandatory Aadhaar-voter ID linkage may fail the test of proportionality, as alternative measures to curb electoral fraud, such as strengthening the verification processes for voter registration, already exist.

The introduction of remote voting raises concerns about the sanctity of the secret ballot, a cornerstone of democratic elections. The Supreme Court, in Kuldip Nayar v. Union of India (2006), underscored the importance of secrecy in voting as an essential feature of free and fair elections. Remote voting systems must address these concerns by ensuring that technological solutions do not compromise voter anonymity. Additionally, questions about the integrity of the process, particularly in scenarios where votes are cast from remote and potentially unsupervised locations, pose legal and ethical challenges.

Blockchain-based voting, while promising enhanced transparency, faces challenges of digital literacy and infrastructure in a country as diverse as India. The legal framework must account for the digital divide and ensure that marginalized communities are not disenfranchised. The implementation of blockchain voting would also necessitate amendments to the Information Technology Act, 2000, to address cybersecurity concerns and define legal standards for electronic records in the context of elections. The challenges of ensuring scalability and reliability in such a system cannot be underestimated, given India’s demographic and geographic diversity.

Judicial Pronouncements on Electoral Reforms

India’s judiciary has played a pivotal role in shaping the electoral landscape through landmark judgments. The Supreme Court’s directive in PUCL v. Union of India (2013) led to the introduction of the NOTA (None of the Above) option, empowering voters to reject all candidates and enhancing their choice. Similarly, the Court’s judgment in Lily Thomas v. Union of India (2013) disqualified convicted legislators, reinforcing the principle of electoral integrity. These judgments underscore the judiciary’s commitment to upholding the principles of democracy and electoral fairness.

In the context of proposed reforms, the judiciary’s stance on privacy, inclusivity, and fairness will be critical. The linkage of Aadhaar with voter IDs, for instance, will likely be scrutinized under the principles laid down in Puttaswamy. Similarly, challenges to remote voting systems will require balancing the need for inclusivity with the sanctity of the electoral process. The judiciary’s role in ensuring that technological advancements do not undermine fundamental rights will be pivotal in shaping the trajectory of these reforms.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Oversight of Electoral Reforms

The Election Commission of India, as the custodian of elections, will play a central role in implementing and regulating the proposed amendments. The ECI’s Model Code of Conduct (MCC) and guidelines on the use of technology will need to be updated to address new challenges posed by remote and blockchain voting systems. Additionally, the Data Protection Bill, once enacted, will have significant implications for the Aadhaar-voter ID linkage and the overall management of electoral data. Ensuring that electoral data is securely stored and managed, while upholding individual privacy, will be a key responsibility of the regulatory framework.

The role of legislative oversight will also be critical. Parliamentary committees must ensure that the proposed amendments are thoroughly debated, addressing concerns of feasibility, inclusivity, and constitutionality. Public consultations and stakeholder engagement, including input from civil society and technical experts, will be essential to crafting a balanced and comprehensive legal framework. Legislative debates must focus on ensuring that the reforms do not exacerbate existing inequalities or create new barriers to voter participation.

International Perspectives and Best Practices

India can draw lessons from international experiences in electoral reforms. Estonia, a pioneer in electronic and internet voting, has demonstrated the potential of technology to enhance voter participation. However, its success hinges on robust cybersecurity measures and widespread digital literacy, both of which remain challenges in the Indian context. Estonia’s experience underscores the importance of ensuring that technological innovations are accompanied by public trust and confidence in the electoral process.

The United States, with its decentralized electoral system, has grappled with issues of voter suppression and technological vulnerabilities. India must learn from these challenges and ensure that its reforms do not inadvertently exclude marginalized communities or compromise the integrity of elections. Transparency, accountability, and inclusivity must remain guiding principles in the design and implementation of electoral reforms.

Conclusion: Enhancing India’s Electoral System through Reform

The proposed amendments to India’s voting system represent a significant opportunity to enhance the inclusivity, transparency, and efficiency of the electoral process. However, these reforms must be approached with caution and deliberation to ensure that the solutions do not introduce new vulnerabilities or exacerbate existing disparities.

Key legal and constitutional challenges, including concerns about privacy, voter secrecy, and technological accessibility, must be carefully addressed. The judiciary, legislature, and Election Commission of India all have critical roles to play in navigating these challenges. Furthermore, public trust must remain a cornerstone of electoral reforms. Without trust in the voting system, even the most advanced technological solutions may fail to achieve their intended outcomes.

Moving forward, a phased and consultative approach will be essential. Pilot projects and incremental implementation can help identify and mitigate risks before scaling up. Public consultations and collaborations with technical experts can ensure that the reforms are both feasible and inclusive. As India seeks to modernize its voting system, it must remain steadfast in upholding the democratic principles enshrined in its Constitution.

In conclusion, while the challenges are formidable, the opportunities presented by these reforms are equally significant. By addressing these issues with foresight and inclusivity, India has the potential to set a global benchmark for electoral innovation and strengthen its democratic fabric for generations to come.

Evaluating the Impact of the Coastal Shipping Bill on India’s Maritime Economy

Introduction

The maritime sector forms the backbone of international trade and commerce, providing a crucial link for the exchange of goods and services across the globe. In India, a nation with a coastline spanning over 7,500 kilometers, the significance of maritime activities cannot be overstated. Coastal shipping, a subset of maritime trade, has emerged as a vital component of the country’s transport network, offering an economical and environmentally sustainable alternative to road and rail transport. The introduction of the Coastal Shipping Bill in India marks a transformative step in harnessing this potential, with far-reaching implications for the nation’s maritime economy.

The Context and Objectives of the Coastal Shipping Bill

India’s maritime sector has historically been regulated by multiple laws and policies that govern ports, shipping, and inland waterways. The Merchant Shipping Act, 1958, and the Inland Vessels Act, 1917 (repealed and replaced by the Inland Vessels Act, 2021), have been central to regulating maritime activities. However, the fragmented nature of these regulations often led to inefficiencies, redundancies, and legal ambiguities. The Coastal Shipping Bill seeks to address these challenges by consolidating and modernizing the regulatory framework.

The primary objectives of the Coastal Shipping Bill include fostering economic growth through enhanced maritime connectivity, reducing logistical costs, promoting sustainable transportation, and creating a level playing field for stakeholders in the coastal shipping ecosystem. By simplifying and harmonizing the regulatory framework, the Bill aims to attract investments, boost employment opportunities, and enhance the competitiveness of India’s maritime sector in the global arena. Furthermore, it intends to create synergies with India’s broader economic policies such as “Make in India” and “Atmanirbhar Bharat,” providing a significant boost to domestic manufacturing and self-reliance.

Key Provisions of the Coastal Shipping Bill

The Coastal Shipping Bill introduces several progressive provisions designed to revitalize India’s maritime economy. First, it defines coastal shipping as a distinct mode of transport, thereby delineating it from inland and international shipping. This clarity facilitates targeted policy interventions and resource allocation. Second, the Bill emphasizes the use of Indian-built, Indian-flagged, and Indian-owned vessels for coastal operations, promoting domestic shipbuilding and enhancing the self-reliance of the sector.

Additionally, the Bill simplifies the process of obtaining permissions and licenses, reducing bureaucratic hurdles for operators. It also incorporates provisions to promote multimodal transportation by integrating coastal shipping with railways, roadways, and inland waterways. This integration is expected to optimize the logistics chain, reduce transit times, and lower transportation costs.

A noteworthy aspect of the Bill is its focus on incentivizing the adoption of green technologies in the maritime sector. By offering financial and policy incentives for the use of low-emission vessels and alternative fuels, the Bill aligns with India’s commitments under international climate agreements, such as the Paris Accord. Moreover, provisions to enhance safety standards, implement advanced navigation systems, and modernize port infrastructure are crucial elements of the Bill.

Regulation and Oversight of Coastal Shipping

The Coastal Shipping Bill is supported by a robust regulatory framework to ensure compliance and accountability. The Directorate General of Shipping (DGS), the apex body responsible for regulating shipping activities in India, is entrusted with enforcing the provisions of the Bill. The DGS oversees the registration and certification of vessels, safety standards, and environmental compliance.

The Bill also aligns with international maritime conventions, including the International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulations, to ensure that India’s coastal shipping standards are on par with global benchmarks. The adoption of these standards is crucial for fostering international collaboration and promoting sustainable maritime practices. Additionally, the establishment of dedicated coastal shipping corridors, with clearly defined routes and operational guidelines, is expected to enhance efficiency and safety in coastal operations.

Legal Precedents and Case Laws

Several landmark judgments and case laws have shaped the regulatory landscape of India’s maritime sector, influencing the formulation of the Coastal Shipping Bill. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Vishaka & Ors. v. State of Rajasthan (1997) laid the foundation for adopting international conventions into domestic law, a principle that finds relevance in aligning the Bill with IMO standards.

In Bharati Shipyard Ltd. v. Deputy Commissioner of Income Tax (2011), the Supreme Court underscored the importance of promoting the domestic shipbuilding industry. This judgment resonates with the Bill’s emphasis on prioritizing Indian-built vessels for coastal shipping operations. By mandating the use of domestically produced ships, the Bill seeks to bolster India’s manufacturing capabilities and reduce reliance on imports.

Another notable case, Intercontinental Consultants and Technocrats Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India (2018), highlighted the need for clarity and simplicity in tax structures to avoid disputes and litigation. The Coastal Shipping Bill’s streamlined licensing and regulatory procedures reflect this principle, reducing the compliance burden for operators. Furthermore, cases like Shipping Corporation of India Ltd. v. Machado Brothers (2004) have provided insights into resolving disputes related to coastal shipping, offering a legal framework that the Bill builds upon.

Economic Implications of the Coastal Shipping Bill

The Coastal Shipping Bill is poised to have a transformative impact on India’s maritime economy. One of its most significant benefits is the potential to reduce logistical costs, which currently account for approximately 13-14% of India’s GDP, compared to the global average of 8-9%. Coastal shipping offers a cost-effective alternative to road and rail transport, particularly for bulk cargo such as coal, steel, and cement. By encouraging a modal shift from road and rail to coastal shipping, the Bill can help reduce transportation costs and enhance the competitiveness of Indian goods in international markets.

The Bill also provides a significant boost to the shipbuilding and repair industry. By mandating the use of Indian-built vessels, it creates a steady demand for domestic shipyards, fostering technological innovation and creating employment opportunities. Furthermore, the development of coastal infrastructure, including ports, terminals, and logistics hubs, is expected to attract private investments and stimulate economic growth in coastal regions. The ripple effect of these developments on ancillary industries, such as manufacturing, technology, and services, is likely to be substantial.

Environmental and Social Benefits

In addition to its economic advantages, the Coastal Shipping Bill promotes environmental sustainability. Coastal shipping is inherently more fuel-efficient and emits lower greenhouse gases compared to road and rail transport. The Bill’s emphasis on multimodal transportation further enhances its environmental credentials by optimizing resource utilization and minimizing wastage. Additionally, the encouragement of green shipping practices and the use of cleaner fuels are expected to significantly reduce the maritime sector’s carbon footprint.

The social impact of the Bill is equally noteworthy. By creating jobs in shipbuilding, port operations, and allied sectors, it contributes to the socio-economic development of coastal communities. Moreover, the enhanced connectivity facilitated by coastal shipping improves access to markets and services, fostering inclusive growth. For fishermen and small-scale traders along India’s coastline, improved infrastructure and reduced transportation costs translate to better livelihoods and increased profitability.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite its many advantages, the Coastal Shipping Bill faces certain challenges and criticisms. One of the primary concerns is the potential resistance from stakeholders in the road and rail transport sectors, who may view the Bill as a threat to their market share. Additionally, the high initial costs associated with developing coastal infrastructure and procuring vessels may deter smaller operators from entering the market.

Another challenge lies in ensuring the effective implementation of the Bill’s provisions. The success of the regulatory framework depends on the efficiency and transparency of enforcement mechanisms, as well as the capacity of the DGS to handle increased responsibilities. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated efforts from the government, industry stakeholders, and regulatory authorities. Moreover, concerns about the adequacy of existing port facilities and the need for substantial investment in modernization and expansion must be addressed.

Global Comparisons and Lessons for India

India can draw valuable lessons from the experiences of other maritime nations in implementing coastal shipping reforms. Countries like the United States, Japan, and Australia have successfully integrated coastal shipping into their transport networks, leveraging its economic and environmental benefits.

For instance, the United States’ Jones Act mandates the use of American-built, American-flagged, and American-crewed vessels for domestic shipping, a policy that aligns with India’s emphasis on self-reliance. Similarly, Japan’s efficient multimodal transport systems offer insights into integrating coastal shipping with other modes of transport. By studying these models, India can fine-tune its policies and address potential challenges in implementing the Coastal Shipping Bill.

Conclusion and the Road Ahead

The Coastal Shipping Bill represents a landmark reform in India’s maritime sector, offering a comprehensive framework to unlock the potential of coastal shipping. Its economic, environmental, and social benefits position it as a critical enabler of India’s aspirations for sustainable and inclusive growth. However, realizing these benefits requires addressing implementation challenges, fostering collaboration among stakeholders, and drawing lessons from global best practices.

As India moves forward with the implementation of the Coastal Shipping Bill, continuous monitoring and evaluation will be crucial to ensure its success. By aligning the regulatory framework with industry needs and global standards, the Bill can serve as a catalyst for transforming India’s maritime economy and strengthening its position as a leading maritime nation. Furthermore, sustained investment in infrastructure, technology, and human capital will be essential to fully realize the transformative potential of the Bill. By adopting a holistic and collaborative approach, India can unlock the vast opportunities offered by coastal shipping, driving long-term growth and sustainability in its maritime sector.

The Role of GST Appellate Tribunals in Streamlining Tax Dispute Resolution

Introduction

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) has been one of the most transformative tax reforms in the history of India’s taxation system. Enacted on July 1, 2017, GST subsumed a myriad of indirect taxes under a single comprehensive framework, bringing uniformity and simplicity to the taxation process. While the GST regime has brought significant benefits, such as ease of doing business and increased compliance, the complexities inherent in its provisions have led to disputes between taxpayers and tax authorities. The GST Appellate Tribunals (GSTAT) were established as a specialized mechanism to address these disputes efficiently and equitably. These tribunals play a critical role in ensuring that tax disputes are resolved in a time-bound manner while maintaining fairness and transparency.

Genesis and Structure of GST Appellate Tribunals

The GST Appellate Tribunal is a quasi-judicial body created under Section 109 of the Central Goods and Services Tax (CGST) Act, 2017. It serves as the second tier of appeal after the decisions of the First Appellate Authority (FAA) or the Revisional Authority. The tribunal’s mandate is to provide a platform for taxpayers and tax authorities to challenge and adjudicate disputes arising under the GST laws.

The structure of the GSTAT is multi-tiered, comprising a National Bench, Regional Benches, State Benches, and Area Benches. The National Bench, located in New Delhi, primarily hears cases involving disputes between two or more states. The Regional Benches, on the other hand, cater to appeals arising within specific geographical jurisdictions. Each bench is composed of three members: a judicial member, a technical member representing the central government, and a technical member representing the state government. This tripartite composition ensures a balanced approach to decision-making, integrating legal expertise with technical knowledge of GST laws.

The Rationale Behind Establishing GST Appellate Tribunals

The establishment of the GST Appellate Tribunals stems from the need for an efficient and specialized dispute resolution mechanism. Prior to the GST regime, disputes arising under various indirect tax laws were addressed through a combination of appellate authorities and judicial forums, including High Courts. This often resulted in significant delays, inconsistencies in rulings, and a lack of uniformity in tax jurisprudence.

Under the GST framework, disputes can arise from diverse issues such as classification of goods and services, valuation of supply, eligibility for input tax credit (ITC), refund claims, and penalties. These matters require adjudication by experts familiar with the nuances of GST laws. The GSTAT addresses this requirement by serving as a dedicated forum for resolving such disputes. Its establishment reduces the burden on the judiciary, facilitates uniform interpretation of GST laws, and provides taxpayers with a reliable avenue for grievance redressal.

Legal Framework Governing GST Appellate Tribunals

The legal foundation for the GST Appellate Tribunals is provided by the CGST Act, 2017, and the corresponding State Goods and Services Tax (SGST) Acts enacted by individual states. Section 109 of the CGST Act mandates the creation of the tribunal, while Section 110 outlines the qualifications and appointment process for its members. These provisions ensure that only individuals with adequate judicial or technical expertise are appointed to the tribunal, maintaining its credibility and effectiveness.

Additionally, Section 113 of the CGST Act delineates the tribunal’s jurisdiction, empowering it to hear and decide appeals on matters arising under the CGST, SGST, and Integrated Goods and Services Tax (IGST) laws. The procedural aspects of filing appeals, representation before the tribunal, and other operational guidelines are detailed in the GST (Appellate Tribunal) Rules, 2019. These rules ensure uniformity and consistency in the functioning of the tribunal across the country.

Challenges in the Implementation of GSTAT

Despite its pivotal role, the establishment and functioning of GSTAT have faced several challenges. One of the primary issues has been the composition of the tribunal’s benches. In the case of Union of India v. Mohit Minerals Pvt. Ltd., the Supreme Court underscored the need for judicial independence in the tribunal’s composition. The court observed that an overrepresentation of technical members at the expense of judicial members could compromise the tribunal’s impartiality and independence.

Another significant challenge pertains to delays in the appointment of tribunal members. In Revenue Bar Association v. Union of India, the Madras High Court emphasized that appointments to tribunals must adhere to the principles laid down in the R. Gandhi judgment, which advocates for judicial primacy in tribunal composition. The lack of timely appointments has resulted in delays in the tribunal’s operationalization, hindering its ability to address disputes efficiently.

Infrastructural constraints and procedural inefficiencies have also impeded the functioning of GSTAT. Many tribunals lack adequate physical and technological infrastructure, limiting their accessibility and efficiency. Moreover, procedural delays in filing and hearing appeals have exacerbated the backlog of cases, undermining the tribunal’s objective of providing swift dispute resolution.

Functions and Jurisdiction of GSTAT

The GST Appellate Tribunal is empowered to adjudicate a wide range of disputes arising under GST laws. Its jurisdiction encompasses matters related to:

- Classification of goods and services under the GST tariff.

- Valuation of supply and determination of tax liability.

- Eligibility and reversal of input tax credit (ITC).

- Refund claims and related disputes.

- Imposition of penalties, interest, and late fees under GST provisions.

- Anti-profiteering provisions and their application.

By addressing these issues, the GSTAT ensures consistency in the interpretation and application of GST laws. Its decisions serve as binding precedents for lower adjudicating authorities, fostering uniformity and reducing ambiguities in tax administration.

The Role of GSTAT in Enhancing Tax Dispute Resolution

The GST Appellate Tribunals have significantly contributed to streamlining tax dispute resolution in India. One of the key benefits of GSTAT is its ability to provide speedy and efficient adjudication of disputes. Unlike conventional judicial forums, which often experience prolonged delays, the tribunal offers a dedicated and time-bound mechanism for resolving tax-related grievances. This not only benefits taxpayers but also enhances the overall efficiency of the tax administration system.

Another critical advantage of GSTAT is its expertise in handling complex tax disputes. The tribunal’s composition, comprising judicial and technical members, ensures that disputes are examined from both legal and technical perspectives. This holistic approach results in well-reasoned and balanced decisions, minimizing the scope for further litigation.

Furthermore, the tribunal’s specialized jurisdiction reduces the burden on higher judiciary, including High Courts and the Supreme Court. By addressing tax disputes at the appellate level, the GSTAT allows higher courts to focus on more critical constitutional and legal matters, contributing to the overall efficiency of the judicial system.

Key Judgments and Precedents

Several landmark judgments by GSTAT and higher courts have significantly influenced the interpretation of GST laws. For example, in M/s Safari Retreats Pvt. Ltd. v. Chief Commissioner of CGST, the Odisha High Court held that ITC on construction activities could be claimed if the property was intended for renting purposes. This judgment emphasized the need for a purposive interpretation of GST provisions, ensuring that taxpayers are not unduly penalized for genuine transactions.

Another important case is K. Raheja Corp. Pvt. Ltd. v. Commissioner of GST, where the tribunal addressed the issue of time limitation for filing appeals. The ruling provided clarity on procedural compliance, highlighting the importance of adhering to statutory timelines while balancing the principles of natural justice.

The tribunal has also played a pivotal role in interpreting the anti-profiteering provisions under Section 171 of the CGST Act. Its decisions have clarified the scope and application of these provisions, ensuring that businesses do not engage in unfair trade practices and that consumers are protected from undue price increases.

Future Prospects and Recommendations for GST Appellate Tribunals

While the GST Appellate Tribunals have made significant strides in improving tax dispute resolution, several challenges remain. To further enhance their effectiveness, the following measures are recommended:

Strengthening the tribunal’s infrastructure is crucial. This includes establishing additional benches in underserved regions, upgrading physical facilities, and integrating advanced technology for e-filing, virtual hearings, and case management. Adequate infrastructure will improve accessibility and reduce delays.

Timely appointment of tribunal members is essential to ensure the tribunal’s uninterrupted functioning. The government must streamline the appointment process and ensure that qualified individuals are appointed to the tribunal without delay. This will help address the backlog of cases and prevent procedural bottlenecks.

Capacity building is another critical area. Regular training programs for tribunal members and staff can enhance their understanding of evolving GST laws and procedures. This will enable them to handle complex disputes more effectively and deliver well-reasoned judgments.

Public awareness initiatives can empower taxpayers to seek remedies through the tribunal. The government and tax authorities should conduct outreach programs to educate taxpayers about the tribunal’s role, jurisdiction, and procedural requirements. Increased awareness will encourage taxpayers to utilize the tribunal’s services and resolve disputes amicably.

Conclusion

The GST Appellate Tribunals represent a cornerstone of India’s tax dispute resolution framework. By providing a dedicated, specialized, and efficient mechanism for resolving GST disputes, the tribunal has strengthened the credibility and reliability of the tax system. Its contributions to ensuring fairness, transparency, and uniformity in tax administration have been invaluable.

As the GST regime continues to evolve, the role of GSTAT will become increasingly important in addressing the challenges posed by complex tax disputes. By addressing its operational challenges and leveraging technology, the tribunal can further enhance its capacity to deliver justice. In doing so, it will reinforce taxpayer confidence in the GST framework, fostering a culture of compliance and contributing to India’s economic growth and development.

Reforms in India’s Criminal Justice System: Replacing Colonial-Era Laws

Introduction

India’s criminal justice system, deeply rooted in the colonial past, has long been a subject of debate and scrutiny. As the country progresses into the twenty-first century, the need for comprehensive reforms to shed the colonial vestiges and create a more equitable and modern justice framework has become paramount. This article delves into the history of India’s criminal justice system, the need for reforms, the steps undertaken so far, and the legal frameworks and case laws shaping the evolution of the system. By expanding on these themes, the article also examines the socio-political implications and the vision for a more inclusive legal system that resonates with contemporary realities.

Historical Context of India’s Criminal Justice System

The origins of the current criminal justice system in India can be traced back to the colonial administration established by the British. Laws such as the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1898 (later revised in 1973), and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, were enacted to serve the interests of the colonial rulers. These laws were designed to maintain control over the population and ensure compliance with colonial authority rather than address the aspirations or welfare of the Indian populace. They were instruments of domination, often applied repressively to suppress dissent and enforce colonial policies.

While these laws provided a foundational framework for criminal jurisprudence, they were not drafted with the needs of an independent, democratic society in mind. Over time, amendments have been introduced to adapt these laws to the changing societal context, but the colonial imprint remains evident in their structure, language, and intent. The rigid framework established by these laws has contributed to a criminal justice system that is often viewed as retributive and punitive, rather than restorative or rehabilitative.

The continuation of these colonial-era laws has resulted in inefficiencies and delays in justice delivery. The inability to address contemporary issues, coupled with systemic weaknesses such as bureaucratic inertia and corruption, underscores the urgency for reform. These shortcomings have fueled demands for a comprehensive overhaul of the criminal justice system to ensure it aligns with the principles of the Indian Constitution and the values of a modern, democratic society.

The Case for Reform of India’s Criminal Justice System

The need for reform in India’s criminal justice system stems from a multitude of systemic challenges. The adversarial nature of the system, inherited from colonial jurisprudence, often results in prolonged trials and delayed justice. The issue of undertrial detainees, who constitute a significant proportion of the prison population, highlights the systemic inefficiencies and the denial of timely justice. Overcrowded prisons, custodial violence, and inadequate legal aid for marginalized sections of society further exacerbate these challenges.

The criminal justice system also suffers from a lack of sensitivity toward victims’ rights. The focus often remains on the accused, with insufficient attention given to the needs of victims for restitution, rehabilitation, and support. This imbalance is symptomatic of a system that prioritizes punishment over restorative justice, leaving little room for reconciliation and community healing.

The persistence of outdated provisions in the IPC, such as sedition under Section 124A, has also drawn widespread criticism. These provisions, originally designed to suppress dissent against colonial rule, are increasingly seen as tools of political suppression in a democratic context. They have been criticized for being inconsistent with the constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and expression, raising questions about their continued relevance in a modern legal framework.

Legal Frameworks for India’s Criminal Justice System

India’s criminal justice system is governed by a robust legal framework that includes the IPC, the CrPC, and the Indian Evidence Act. These laws define crimes, prescribe punishments, establish procedural safeguards, and regulate the admissibility of evidence. Together, they form the backbone of the criminal justice system, influencing the actions of law enforcement agencies, the judiciary, and correctional institutions.

The Constitution of India plays a critical role in shaping the criminal justice system by enshrining fundamental rights that guarantee protection against arbitrary actions by the state. Articles 20, 21, and 22 are particularly significant in this regard. Article 20 prohibits double jeopardy and retrospective punishment, while Article 21 guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, which includes the right to a fair trial. Article 22 provides safeguards against arbitrary arrest and detention, ensuring procedural fairness.

Judicial interpretations have further expanded these rights, enhancing the accountability of the criminal justice system. Landmark judgments have underscored the importance of fair procedure, protection of human rights, and the need for a balance between state power and individual liberties. These judicial interventions have often acted as catalysts for reform, highlighting gaps in the legal framework and driving policy changes.

Path to Reform in India’s Criminal Justice System

Recognizing the pressing need for reform, the Indian government has undertaken various initiatives to modernize the criminal justice system. The Malimath Committee Report (2003) was a watershed moment in this regard. The committee proposed a shift toward a more victim-centric approach, emphasizing the need for speedy trials, the protection of victims’ rights, and the adoption of restorative justice principles. It also recommended measures to reduce delays in the justice delivery process, such as increasing the use of technology and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

While the Malimath Committee’s recommendations provided a roadmap for reform, their implementation has been uneven. Legislative measures such as the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, introduced in the wake of the Nirbhaya case, marked significant progress in addressing gender-based violence. The act expanded the definition of sexual offenses, increased penalties, and introduced procedural safeguards to protect victims. However, gaps remain in the implementation of these provisions, particularly in ensuring effective enforcement and providing support to victims.

The Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022, represents another step toward modernization by expanding the scope of evidence collection through biometric and other forms of data. While this has the potential to enhance investigative capabilities, it has also raised concerns about privacy and the risk of misuse. These debates underscore the need for a careful balancing of technological advancements with safeguards to protect individual rights.

Judicial Interventions and Landmark Judgments

The judiciary has played a pivotal role in addressing systemic issues and advancing reforms in the criminal justice system. Landmark judgments have not only highlighted deficiencies but also set important precedents for upholding constitutional principles.

In the case of Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), the Supreme Court expanded the scope of Article 21, holding that the right to life and personal liberty encompasses a fair and reasonable procedure. This judgment has had far-reaching implications for ensuring procedural fairness in the criminal justice system.

The judgment in D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal (1997) laid down guidelines to prevent custodial torture, emphasizing the need for accountability and transparency in law enforcement. Similarly, the decision in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015), which struck down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, underscored the judiciary’s role in protecting fundamental freedoms against arbitrary state actions.

The decriminalization of consensual same-sex relationships in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018) marked a significant step toward inclusivity and equality, challenging the colonial morality that underpinned provisions like Section 377 of the IPC. These judgments highlight the judiciary’s proactive role in addressing systemic injustices and aligning the criminal justice system with contemporary constitutional values.

Key Challenges in Criminal Justice Reform Implementation

Despite the progress made, significant challenges persist in implementing reforms. Structural issues such as inadequate infrastructure, lack of coordination among stakeholders, and limited financial resources hinder the effective functioning of the criminal justice system. The backlog of cases in courts, resulting in prolonged delays, continues to be a major concern, undermining public confidence in the justice delivery mechanism.

Law enforcement practices also require urgent attention. The reliance on confessions as evidence, often extracted under duress, highlights the need for scientific and humane methods of investigation. The lack of forensic infrastructure and trained personnel further hampers the quality of evidence, impacting the outcome of trials.

Custodial violence and the abuse of power by law enforcement agencies remain pressing issues, reflecting a systemic failure to uphold human rights. The absence of adequate training and sensitization among police personnel exacerbates problems such as gender-based discrimination and the marginalization of vulnerable groups.

International Comparisons and Best Practices

India can benefit from studying the experiences of other countries that have successfully reformed their criminal justice systems. The plea bargaining system in the United States, for example, has significantly reduced the burden on courts and expedited the resolution of cases. Similarly, the restorative justice practices adopted in countries like New Zealand and Norway prioritize reconciliation, community involvement, and the rehabilitation of offenders, offering an alternative to punitive approaches.

Incorporating such practices into India’s legal framework, while tailoring them to the socio-cultural context, can enhance the efficiency and inclusivity of the criminal justice system. Measures such as community policing, alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, and victim support programs can address localized issues and reduce the reliance on formal judicial processes.

The Way Forward for India’s Criminal Justice Reform

Replacing colonial-era laws and building a modern criminal justice system requires a holistic approach that combines legislative, procedural, and institutional reforms. Legislative measures should focus on repealing outdated provisions, introducing proportional punishments, and protecting victims’ rights. Procedural reforms must leverage technology to streamline investigations, improve case management, and ensure transparency in judicial processes.

Capacity building among stakeholders is essential to address systemic issues. Training programs for judges, police officers, and correctional personnel should emphasize human rights, gender sensitivity, and modern investigative techniques. Public awareness campaigns can empower citizens to demand accountability and exercise their rights, fostering greater trust in the justice delivery system.

Conclusion

The transformation of India’s criminal justice system is not merely a legal necessity but a socio-political imperative. By replacing colonial-era laws with a progressive and inclusive framework, India can create a justice system that is responsive to the needs of its people and reflective of constitutional values. The journey toward reform is challenging, but with sustained efforts, collaboration among stakeholders, and a commitment to justice, liberty, and equality, India can pave the way for a more equitable and just society.