Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

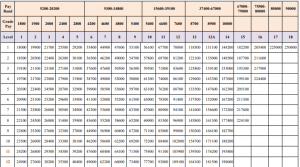

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

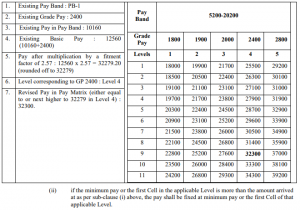

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

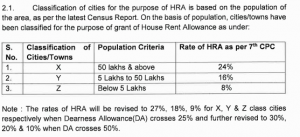

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

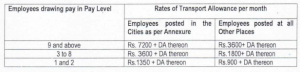

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Cross-Border Taxation and India’s GAAR: Conflict or Coherence?

Introduction

In an era of globalized business operations and sophisticated cross-border tax planning, nations worldwide have been compelled to develop robust anti-avoidance frameworks to protect their tax base. India’s response to this challenge culminated in the introduction of General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) under Chapter X-A of the Income Tax Act, 1961, effective from April 1, 2017. These provisions represent a paradigm shift in India’s approach to tax avoidance, moving from specific anti-avoidance rules targeting particular transactions to a principles-based framework addressing the substance of arrangements. The implementation of GAAR has raised significant questions about its interaction with existing cross-border taxation frameworks, including tax treaties, transfer pricing regulations, and specific anti-avoidance rules. This article examines the complex relationship between India’s GAAR provisions and cross-border taxation, analyzing areas of potential conflict and coherence. It delves into the statutory framework, judicial interpretations, international comparisons, and practical implications for taxpayers engaged in cross-border activities. Through this analysis, the article aims to provide clarity on whether GAAR complements or conflicts with existing cross-border tax frameworks, offering insights into navigating this complex terrain.

Statutory Framework of India’s GAAR Provisions

Legislative Evolution

The journey toward implementing GAAR in India has been marked by extensive deliberation and multiple revisions. The provisions were first introduced by the Direct Taxes Code Bill, 2010, but were subsequently incorporated into the Income Tax Act through the Finance Act, 2012. Following concerns from various stakeholders, their implementation was deferred multiple times before finally taking effect from April 1, 2017.

Section 95 of the Income Tax Act establishes the foundational premise of GAAR:

“Notwithstanding anything contained in the Act, an arrangement entered into by an assessee may be declared to be an impermissible avoidance arrangement and the consequence in relation to tax arising therefrom may be determined subject to the provisions of this Chapter.”

This provision explicitly overrides other provisions of the Act, signaling the legislature’s intent to give GAAR precedence in cases of conflict with other provisions.

Key Concepts and Definitions

The GAAR framework hinges on several critical concepts:

- Impermissible Avoidance Arrangement (IAA): Section 96(1) defines an arrangement as an IAA if its main purpose is to obtain a tax benefit and it satisfies any of the four specified tests:

“(a) creates rights, or obligations, which are not ordinarily created between persons dealing at arm’s length;

(b) results, directly or indirectly, in the misuse, or abuse, of the provisions of this Act;

(c) lacks commercial substance or is deemed to lack commercial substance under section 97, in whole or in part; or

(d) is entered into, or carried out, by means, or in a manner, which are not ordinarily employed for bona fide purposes.” - Lack of Commercial Substance: Section 97 elaborates on this concept, specifying various scenarios where an arrangement shall be deemed to lack commercial substance, including:

- Substance or effect of the arrangement as a whole differs significantly from the form

- Round-trip financing or accommodating party involvement

- Elements that have effect of offsetting or canceling each other

- Transactions conducted through tax-favorable jurisdictions

- Tax Benefit: Defined in Section 102(10) as:

“(a) a reduction or avoidance or deferral of tax or other amount payable under this Act; or

(b) an increase in a refund of tax or other amount under this Act; or

(c) a reduction in total income; or

(d) an increase in loss, in the relevant previous year or any other previous year”

Consequences and Procedural Safeguards

Section 98 outlines the consequences of an arrangement being declared an IAA, which may include:

- Disregarding, combining, or recharacterizing the arrangement

- Treating the arrangement as if it had not been entered into

- Reallocating income, expenses, relief, or tax credits

- Recharacterizing equity as debt, capital as revenue, etc.

Procedural safeguards are established in Section 144BA, requiring approval from the Principal Commissioner or Commissioner before invoking GAAR and providing the taxpayer with an opportunity to be heard. For cases exceeding specified thresholds, approval from an Approving Panel comprising three members is mandatory.

Rule 10U further provides specific exclusions, including:

- Arrangements where the tax benefit does not exceed ₹3 crore

- Foreign Institutional Investors not claiming treaty benefits

- Non-resident investments in FIIs

- Income from transfer of investments made before April 1, 2017

India’s GAAR and Taxation Treaties: Navigating the Overlap

The Treaty Override Question

A central question in the GAAR-treaty relationship is whether domestic GAAR provisions can override tax treaty benefits. Section 90(2) of the Income Tax Act provides that the provisions of the Act shall apply to the extent they are more beneficial to the assessee than the treaty provisions. However, Section 95 begins with “Notwithstanding anything contained in the Act,” creating potential ambiguity about its application to treaty benefits.

The CBDT Circular No. 7 of 2017 attempted to clarify this issue:

“It is declared that GAAR provisions shall not apply to such right of the assessee as expressly granted under the treaty which is unambiguous. However, in case a tax treaty contains specific anti-avoidance rules (such as Limitation of Benefits), the same shall continue to apply even if GAAR is invoked.”

This formulation suggests a nuanced approach where GAAR may override treaty benefits in cases of ambiguity or where the treaty itself does not expressly prohibit application of domestic anti-avoidance rules.

Judicial Guidance on Treaty-GAAR Interaction

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Union of India v. Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003) 263 ITR 706, which predates GAAR, recognized tax planning as legitimate but distinguished it from colorable devices. The Court observed:

“It is well settled that the benefits of a tax treaty can be legitimately availed of by tax planning that is not a colorable device. However, where the sole purpose of an arrangement is to avoid tax without any commercial substance, the revenue authorities are not precluded from examining its true nature.”

Post-GAAR implementation, the Authority for Advance Rulings in Tiger Global International II Holdings (AAR No. 1555 of 2019) addressed the interplay between GAAR and the India-Mauritius tax treaty. The AAR observed:

“The GAAR provisions enable examination of the substance of arrangements that appear designed primarily to access treaty benefits without sufficient economic substance. This is consistent with the international principle that treaties should be interpreted in good faith and in light of their object and purpose.”

Principal Purpose Test and GAAR

The introduction of the Principal Purpose Test (PPT) in India’s tax treaties, particularly through the Multilateral Instrument (MLI), has added another layer to the treaty-GAAR interaction. The PPT denies treaty benefits if obtaining such benefits was one of the principal purposes of an arrangement.

In AB Holdings Ltd. v. Commissioner of Income-tax (2023), the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal Delhi observed:

“The Principal Purpose Test under the MLI and India’s GAAR provisions share conceptual similarities in focusing on the purpose of arrangements. However, they remain distinct legal instruments with different thresholds and consequences. While PPT applies specifically to treaty benefits, GAAR has broader application to the provisions of the Income Tax Act.”

GAAR and Transfer Pricing: Dual Anti-Avoidance Frameworks

Conceptual Relationship

Transfer Pricing (TP) regulations under Section 92 to 92F of the Income Tax Act and GAAR represent two distinct anti-avoidance frameworks with potential overlap. While TP provisions focus specifically on pricing of international transactions between associated enterprises, GAAR addresses broader tax avoidance arrangements.

Rule 10U(1)(d) provides that GAAR shall not apply to “any arrangement where the main purpose of a part or step thereof is to obtain a tax benefit, but the main purpose of the overall arrangement is not to obtain a tax benefit.” This creates potential confusion in the context of transfer pricing adjustments, where the primary purpose of the transaction might be commercial but the pricing aspect might be motivated by tax considerations.

Judicial Clarifications

The Mumbai Bench of the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal in Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd. v. ACIT (ITA No. 8458/Mum/2010) provided some clarity:

“Transfer pricing provisions operate within a specific domain, addressing the arm’s length pricing of international transactions between associated enterprises. GAAR, on the other hand, examines the overall arrangement to determine if its main purpose is to obtain a tax benefit. These provisions should be viewed as complementary rather than conflicting, with transfer pricing being the first line of defense against pricing manipulation and GAAR serving as a broader anti-avoidance measure.”

CBDT Circular Guidance

CBDT Circular No. 7 of 2017 addressed the GAAR-TP relationship:

“GAAR and SAAR can coexist and are applicable, as may be necessary, in the facts and circumstances of the case. In a case where SAAR is applicable, GAAR may not be invoked. However, in cases of abusive, contrived and artificial arrangements, as illustrated below, GAAR may be invoked.”

The circular provided illustrative examples where GAAR might apply despite transfer pricing provisions, including:

- Arrangements involving interpositioning of entities without commercial substance

- Substantive commercial activities carried through low-tax jurisdictions with minimal economic substance

- Complex structuring with no commercial substance

GAAR and Specific Anti-Avoidance Rules: Finding Harmony

Statutory Relationship

Besides transfer pricing, the Income Tax Act contains numerous Specific Anti-Avoidance Rules (SAARs) addressing particular types of tax avoidance, including:

- Section 94 (Dividend stripping)

- Section 40A (Transactions with related persons)

- Section 80IA(8) (Inter-unit transfer pricing)

- Section 2(22)(e) (Deemed dividend)

The relationship between these SAARs and GAAR is addressed in Rule 10U(1)(c), which states that GAAR shall not apply where “the tax benefit arises from the arrangement is explicitly granted by the provisions of the direct tax laws.”

Judicial Interpretation

The Delhi High Court in CIT v. Hindustan Coca Cola Beverages Pvt. Ltd. (2021) 438 ITR 226 considered the relationship between GAAR and SAARs:

“The General Anti-Avoidance Rules and Specific Anti-Avoidance Rules represent complementary approaches to addressing tax avoidance. Where a specific provision adequately addresses a particular type of avoidance, the need to invoke the more general provision may be diminished. However, where the specific provision is circumvented through a complex arrangement beyond its explicit scope, GAAR provides a necessary backstop.”

International Perspective

The approach of treating GAAR and SAARs as complementary is consistent with international practice. In the United Kingdom case of Schofield v. HMRC [2012] UKFTT 398, the First-tier Tribunal observed:

“Specific anti-avoidance provisions target known avoidance schemes and provide certainty in their application. General anti-avoidance rules, by contrast, address the mischief of avoidance more broadly, preventing the exploitation of gaps or unintended consequences in specific provisions. Both serve important functions in a comprehensive anti-avoidance framework.”

Extraterritorial Application of GAAR

Statutory Scope

The potential extraterritorial application of GAAR arises from its focus on “arrangements” rather than specific transactions or entities. Section 102(1) defines “arrangement” broadly as:

“any step in, or a part or whole of, any transaction, operation, scheme, agreement or understanding, whether enforceable or not, and includes the alienation of any property in such transaction, operation, scheme, agreement or understanding.”

This definition, coupled with the fact that Section 96 does not explicitly limit GAAR’s application to domestic arrangements, creates the possibility of its application to arrangements wholly or partly outside India.

Jurisdictional Considerations

The question of GAAR’s extraterritorial application was considered by the Authority for Advance Rulings in Mahindra British Telecom Ltd. (AAR No. 869 of 2010), albeit in a pre-implementation context:

“While tax laws primarily operate within territorial boundaries, they may extend to foreign elements where there is a sufficient nexus with the taxing jurisdiction. In the context of GAAR, this nexus would typically be established through the tax benefit arising in India, regardless of where the arrangement is executed or implemented.”

Comparative Approaches

Australia’s GAAR provisions under Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 have been applied to arrangements with foreign elements. In Federal Commissioner of Taxation v. Spotless Services Ltd. (1996) 186 CLR 404, the High Court of Australia upheld the application of GAAR to an arrangement involving investments in the Cook Islands.

Similarly, Canada’s GAAR under Section 245 of the Income Tax Act has been applied to cross-border arrangements. In Canada Trustco Mortgage Co. v. Canada [2005] 2 SCR 601, the Supreme Court of Canada noted that GAAR could apply to transactions with foreign elements where they result in tax benefits within Canada.

India’s GAAR Effect on Cross-Border Taxation Structures

Impact on Holding Company Structures

Multinational enterprises frequently establish holding company structures in jurisdictions with favorable tax treaties to manage investments efficiently. Following GAAR implementation, such structures face increased scrutiny.

In Aditya Birla Nuvo Ltd. (AAR No. 1177 of 2011), the Authority for Advance Rulings examined a holding structure involving Mauritius and observed:

“The mere interposition of a holding company in a tax-favorable jurisdiction does not per se constitute impermissible avoidance. However, where such a company lacks economic substance and exists primarily to access treaty benefits, it may fall within the ambit of GAAR.”

Key factors that tax authorities consider in evaluating holding structures include:

- Substance in the holding jurisdiction (staff, premises, decision-making)

- Business rationale beyond tax benefits

- Actual control and management of the holding entity

- Economic activities beyond passive holding

Implications for M&A Transactions

Cross-border mergers and acquisitions often involve complex structuring to optimize tax outcomes. Post-GAAR, such transactions require careful consideration of both form and substance.

In Vodafone International Holdings BV v. Union of India (2012) 341 ITR 1, the Supreme Court had held that the transfer of shares of a foreign company that indirectly held Indian assets was not taxable in India. However, this position was subsequently altered through retrospective amendments to the Income Tax Act.

In the GAAR era, similar transactions would face scrutiny under Section 96(1) to determine if they constitute IAAs. The Mumbai bench of the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal in NGC Networks (India) Pvt. Ltd. (ITA No. 7994/Mum/2011) noted:

“Cross-border M&A transactions must be examined not merely for legal compliance but also for their commercial substance. Where the structure exists primarily to achieve tax benefits rather than commercial objectives, GAAR provisions may apply to recharacterize the arrangement based on its substance.”

Impact on Financing Structures

Under the framework of Cross-Border taxation and India’s GAAR Provisions, financing arrangements—including hybrid instruments, thin capitalization structures, and back-to-back loans—face particular scrutiny.

In Zaheer Mauritius v. DIT (2014) 270 CTR 214, the Authority for Advance Rulings examined a financing structure involving a Mauritius entity and observed:

“Financing arrangements must reflect genuine commercial relationships rather than mere tax-driven structures. Where the form of financing (such as debt versus equity) is chosen primarily for tax advantages rather than commercial considerations, there is potential for GAAR application.”

Key risk factors in financing structures include:

- Artificial debt-equity ratios inconsistent with commercial norms

- Interest rates substantially diverging from market rates

- Back-to-back arrangements with minimal spread

- Financing through entities with no substantive functions

Judicial Approaches to GAAR Application

Emerging Judicial Standards

While comprehensive judicial guidance on GAAR application remains limited due to its relatively recent implementation, emerging decisions provide insight into developing standards.

In Ardex Investments Mauritius Ltd. (AAR No. 1428 of 2012), the Authority for Advance Rulings outlined an analytical framework:

“The application of GAAR requires a multi-step analysis: first, identifying the arrangement; second, determining whether the main purpose of the arrangement is to obtain a tax benefit; third, assessing whether the arrangement satisfies any of the four tests under Section 96(1); and finally, determining the appropriate consequences under Section 98.”

Burden and Standard of Proof

The question of who bears the burden of proof in GAAR cases has been addressed in various forums. In Khatau Holdings and Investment Pvt. Ltd. v. ACIT (ITA No. 5104/Mum/2018), the Mumbai ITAT observed:

“While the initial burden rests with the tax authority to demonstrate prima facie that an arrangement constitutes an IAA, once this threshold is met, the onus shifts to the taxpayer to establish that obtaining a tax benefit was not the main purpose of the arrangement and that it has commercial substance beyond tax considerations.”

Regarding the standard of proof, the Delhi High Court in CIT v. Dalmia Promoters Pvt. Ltd. (2018) 408 ITR 375 noted:

“GAAR provisions represent an extraordinary power and must be applied with caution. The standard of proof required is not mere suspicion but clear and convincing evidence that the main purpose of the arrangement is to obtain a tax benefit and that it lacks commercial substance or otherwise satisfies the criteria under Section 96(1).”

Relevance of Non-Tax Commercial Considerations

A recurring theme in GAAR jurisprudence is the evaluation of non-tax commercial considerations. In Serco BPO Private Limited v. AAR (2015) 379 ITR 256, the Punjab and Haryana High Court emphasized:

“The existence of tax benefits does not automatically trigger GAAR. Where an arrangement is supported by substantive commercial considerations, the mere fact that it is structured in a tax-efficient manner does not render it impermissible. The assessment must consider the totality of the arrangement, including both tax and non-tax factors.”

International Perspectives and Harmonization

OECD’s BEPS Initiatives and Indian GAAR

The OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project represents a global response to tax avoidance, with Action 6 (Preventing Treaty Abuse) and Action 7 (Preventing the Artificial Avoidance of Permanent Establishment Status) having particular relevance to GAAR.

In Macquarie Bank Limited v. Commissioner of Income Tax (2022) 443 ITR 189, the Delhi High Court observed:

“India’s GAAR provisions align conceptually with the OECD’s BEPS initiatives, particularly regarding substance over form and the prevention of treaty abuse. This alignment facilitates a harmonized approach to cross-border tax avoidance while respecting India’s unique economic context and treaty network.”

Comparative Analysis with Foreign GAARs

India’s GAAR shares conceptual similarities with similar provisions in other jurisdictions but also contains distinctive elements:

- UK’s GAAR: Introduced in 2013, requires a “double reasonableness” test where arrangements must be “not reasonable” and requires approval from an independent GAAR Advisory Panel before application.

- Australian GAAR: Part IVA requires identification of a “scheme” and a “tax benefit” and applies where obtaining the tax benefit was the “sole or dominant purpose” of the scheme.

- South African GAAR: Section 80A-L of the Income Tax Act applies where the “sole or main purpose” was to obtain a tax benefit and contains similar tainted elements to India’s GAAR.

In Vodafone India Services Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India (2014) 368 ITR 1, the Bombay High Court noted:

“While international precedents on GAAR application provide valuable guidance, India’s GAAR must be interpreted within its specific statutory context and constitutional framework. Foreign decisions, while persuasive, cannot be mechanically applied without considering these contextual differences.”

Treaty Policy Evolution

India’s treaty policy has evolved significantly in the GAAR era, with newer treaties incorporating anti-abuse provisions. The renegotiation of the India-Mauritius treaty in 2016, removing the capital gains tax exemption, exemplifies this evolution.

In AB Holdings Ltd. v. DIT (AAR No. 1505 of 2013), the Authority for Advance Rulings observed:

“India’s treaty policy has undergone a paradigm shift toward preventing treaty abuse while maintaining incentives for legitimate investment. GAAR should be viewed as complementary to this evolving treaty policy rather than conflicting with it.”

Practical Strategies for GAAR Compliance

Substance Requirements of GAAR Compliance in Cross-Border Taxation

Establishing and maintaining substance in cross-border structures is paramount for compliance with Cross-Border taxation and India’s GAAR provisions. Key substance elements include:

- Physical Presence: Adequate office space and equipment

- Qualified Personnel: Employees with relevant expertise

- Decision-Making Authority: Board meetings with substantive discussions

- Financial Substance: Adequate capitalization and genuine financial risk

In Universal Leather Uplift Ltd. (AAR No. 1299 of 2012), the Authority for Advance Rulings emphasized:

“Substance cannot be established through mere formal compliance with incorporation requirements or minimal physical presence. It requires demonstration of genuine economic activities and decision-making functions commensurate with the entity’s purported role in the structure.”

Documentation and Evidence for GAAR Compliance

Maintaining robust documentation to demonstrate commercial rationale is critical for defending against GAAR challenges. Essential documentation includes:

- Board resolutions detailing business rationale

- Contemporaneous evidence of commercial considerations

- Transfer pricing documentation establishing arm’s length dealings

- Evidence of substance in each entity within the structure

The Income Tax Appellate Tribunal in Bayer Material Science Private Limited (ITA No. 1112/Mum/2016) noted:

“Contemporaneous documentation that demonstrates genuine commercial objectives beyond tax considerations serves as persuasive evidence against GAAR application. The absence of such documentation creates a presumption that tax benefits were a primary consideration.”

Advance Rulings and Certifications

Seeking advance rulings on potential GAAR application provides certainty for complex transactions. Section 245N allows applications for advance rulings on whether an arrangement would be treated as an IAA.

In Microsoft Corporation (India) Pvt. Ltd. (AAR No. 1455 of 2013), the AAR observed:

“An advance ruling provides valuable certainty regarding tax implications, particularly for complex cross-border arrangements potentially scrutinized under GAAR. However, the effectiveness of such rulings depends on full and accurate disclosure of all material facts relating to the arrangement.”

Future Trajectory and Recommendations

Legislative Refinements

Several potential legislative refinements could enhance the clarity and effectiveness of Cross-Border taxation and India’s GAAR provisions in practice:

- Clearer Safe Harbors: Expanding and clarifying safe harbor provisions to provide greater certainty for routine commercial arrangements.

- Standardized Documentation Requirements: Establishing clear documentation requirements for demonstrating commercial substance.

- Harmonized Application with Tax Treaties: Explicit provisions addressing the interaction between GAAR and tax treaties, particularly in light of the MLI.

Procedural Improvements

Procedural improvements could enhance GAAR’s effectiveness while maintaining taxpayer protections:

- Specialized GAAR Panels: Establishing specialized panels with cross-border taxation expertise to ensure consistent application.

- Time-Bound Approvals: Implementing strict timelines for GAAR approvals to enhance certainty.

- Advance Compliance Programs: Developing cooperative compliance programs allowing taxpayers to proactively address GAAR concerns.

International Coordination

Enhanced international coordination could mitigate conflicts between India’s GAAR and foreign tax systems:

- Mutual Agreement Procedures: Explicitly incorporating GAAR considerations into Mutual Agreement Procedures under tax treaties.

- Joint Audits: Implementing joint audit mechanisms with treaty partners for complex cross-border arrangements.

- Multilateral Exchange of Information: Leveraging enhanced exchange of information to better assess the substance of cross-border arrangements.

Conclusion

Cross-Border taxation and India’s GAAR provisions represent a significant evolution in India’s approach to cross-border tax avoidance, shifting from formalistic to substantive assessment of arrangements. The analysis reveals that rather than creating irreconcilable conflicts with existing cross-border taxation frameworks, GAAR largely complements these frameworks by providing a principles-based backstop against sophisticated avoidance arrangements.

The relationship between GAAR and tax treaties, transfer pricing regulations, and specific anti-avoidance rules is characterized by both tension and coherence. While potential conflicts exist, particularly regarding treaty override, the emerging jurisprudence suggests a balanced approach that respects treaty obligations while preventing their abuse through artificial arrangements.

For multinational enterprises operating in India, Cross-Border Taxation and India’s GAAR Provisions necessitate a fundamental shift in approach – from focusing predominantly on legal compliance to ensuring that arrangements have substantive commercial rationale beyond tax benefits. This shift aligns with global trends toward substance-based taxation, as reflected in the OECD’s BEPS initiatives.

As GAAR jurisprudence continues to evolve, clearer standards and more predictable application can be expected. The challenge for both tax authorities and taxpayers lies in finding the appropriate balance between preventing abusive arrangements and providing certainty for legitimate business structures. Achieving this balance will require ongoing dialogue, refined guidance, and judicial wisdom to ensure that GAAR fulfills its intended purpose without unduly burdening cross-border commerce.In the final analysis, the question of whether Cross-Border taxation and India’s GAAR provisions conflict or cohere with cross-border taxation frameworks does not yield a binary answer. Rather, the relationship is nuanced, dynamic, and context-dependent. With appropriate application, GAAR has the potential to strengthen India’s cross-border taxation framework by addressing avoidance arrangements that existing provisions cannot adequately combat, thereby enhancing both integrity and equity in the tax system.

Judicial Review of Advance Rulings under GST: Scope and Limitations

Introduction

The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in July 2017 marked a watershed moment in India’s indirect tax regime, consolidating multiple taxes into a unified structure. To provide certainty in this new tax landscape, the GST law incorporated the Advance Ruling mechanism – a procedure that allows taxpayers to obtain binding clarifications on specified GST issues before undertaking transactions. While this mechanism aims to provide tax certainty, questions have emerged regarding the scope and limitations of judicial review over such rulings, particularly given their binding nature and limited statutory appeal provisions. This article examines the intricate relationship between Advance Rulings under GST and the constitutional power of judicial review vested in High Courts and the Supreme Court. It navigates through the statutory framework, analyzes landmark judicial pronouncements, identifies key challenges, and explores potential reforms to enhance the effectiveness of this critical aspect of GST administration. The analysis is particularly relevant as the jurisprudence on GST Advance Rulings continues to evolve, shaping both administrative practice and taxpayer strategies in this still-maturing tax regime.

Statutory Framework of Advance Rulings under GST

Legal Provisions of GST Advance Ruling Mechanism

The Advance Ruling mechanism under GST derives its statutory foundation from Chapter XVII of the Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017 (CGST Act), comprising Sections 95 to 106. Parallel provisions exist in the respective State GST Acts, creating a comprehensive framework for Advance Rulings at both central and state levels.

Section 95 defines “advance ruling” with remarkable breadth:

“‘advance ruling’ means a decision provided by the Authority or the Appellate Authority or the National Appellate Authority to an applicant on matters or on questions specified in sub-section (2) of section 97 or sub-section (1) of section 100 or of section 101C of this Act, in relation to the supply of goods or services or both being undertaken or proposed to be undertaken by the applicant.”

Section 97(2) specifies the questions on which advance ruling can be sought, including:

“(a) classification of any goods or services or both; (b) applicability of a notification issued under the provisions of this Act; (c) determination of time and value of supply of goods or services or both; (d) admissibility of input tax credit of tax paid or deemed to have been paid; (e) determination of the liability to pay tax on any goods or services or both; (f) whether applicant is required to be registered; (g) whether any particular thing done by the applicant with respect to any goods or services or both amounts to or results in a supply of goods or services or both, within the meaning of that term.”

Institutional Structure of GST Advance Ruling Authorities

The GST law establishes a multi-layered institutional structure for Advance Rulings:

- Authority for Advance Ruling (AAR): Constituted in each State/UT under Section 96, comprising one member from the central tax authorities and one from the state tax authorities.

- Appellate Authority for Advance Ruling (AAAR): Established under Section 99, consisting of the Chief Commissioner of central tax and Commissioner of state tax, to hear appeals against AAR orders.

- National Appellate Authority for Advance Ruling (NAAR): Introduced through the Finance (No. 2) Act, 2019, under Section 101A, to resolve conflicting advance rulings issued by AARs of different states.

Binding Nature and Appeal Provisions under GST Advance Ruling

Section 103 explicitly states that an advance ruling shall be binding on:

“(a) the applicant who had sought it; and (b) the concerned officer or the jurisdictional officer in respect of the applicant.”

The binding nature of these rulings is complemented by limited statutory appeal provisions:

- Section 100 allows appeals to AAAR within 30 days (extendable by 30 days) on grounds of dissatisfaction with the AAR’s ruling.

- Section 101B provides for appeals to NAAR within 30 days (extendable by 30 days) in cases of conflicting advance rulings.

Importantly, the GST law does not explicitly provide for further appeals beyond AAAR or NAAR, raising questions about the finality of these rulings and the scope for judicial review by constitutional courts.

Constitutional Framework for Judicial Review

Writ Jurisdiction of High Courts

Article 226 of the Constitution confers upon High Courts the power to issue writs, including writs of certiorari, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and habeas corpus. This power extends to “any person or authority” within the territorial jurisdiction of the High Court “for the enforcement of any of the rights conferred by Part III and for any other purpose.”

The Supreme Court, in Whirlpool Corporation v. Registrar of Trademarks, Mumbai (1998) 8 SCC 1, clarified the scope of this power:

“The power to issue prerogative writs under Article 226 of the Constitution is plenary in nature and is not limited by any other provision of the Constitution. This power can be exercised by the High Court not only for issuing writs in the nature of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari for the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights contained in Part III of the Constitution but also for ‘any other purpose’.”

Supervisory Jurisdiction of Supreme Court

Article 32 of the Constitution guarantees the right to move the Supreme Court for enforcement of fundamental rights, while Article 136 empowers the Supreme Court to grant special leave to appeal from any judgment, decree, determination, sentence, or order in any cause or matter passed or made by any court or tribunal in India.

In L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997) 3 SCC 261, the Supreme Court held:

“The jurisdiction conferred upon the High Courts under Articles 226 and 227 and upon the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Constitution is part of the inviolable basic structure of our Constitution.”

This constitutional position establishes that the power of judicial review remains inviolable and cannot be curtailed even by statutory provisions purporting to grant finality to administrative decisions.

Scope of Judicial Review of Advance Rulings under GST

Grounds for Judicial Review of GST Advance Rulings

The scope of judicial review over GST Advance Rulings has been shaped by evolving judicial pronouncements. Based on established principles of administrative law and specific GST-related decisions, the following grounds for judicial review have emerged:

- Jurisdictional Errors

In Columbia Asia Hospitals Pvt. Ltd. v. Commissioner of Commercial Taxes (2019) 25 GSTL 385 (Karnataka High Court), the court intervened where the AAR had exceeded its jurisdiction by ruling on questions not specifically sought by the applicant. The court observed:

“The Authority for Advance Ruling cannot travel beyond the questions referred to it and adjudicate on matters not specifically sought. Such an exercise would be ultra vires and subject to correction through judicial review.”

- Errors of Law

The Bombay High Court in Dharmendra M. Jani v. Union of India [2021-TIOL-1817-HC-MUM-GST] emphasized that errors of law apparent on the face of the record would warrant judicial intervention:

“While the GST law grants finality to Advance Rulings within their statutory context, this finality cannot extend to palpable errors of law that strike at the root of the ruling. The constitutional courts retain the power to correct such errors through their writ jurisdiction.”

- Violation of Natural Justice

In Enfield Apparels Ltd. v. Authority for Advance Ruling [2020-TIOL-1323-HC-MAD-GST], the Madras High Court set aside an advance ruling where the applicant was not provided adequate opportunity to present their case:

“The principles of natural justice are not mere formalities but substantive safeguards that ensure fair decision-making. Their violation in the advance ruling process renders the resulting determination susceptible to judicial review, notwithstanding the statutory limitations on appeals.”

- Unreasonable or Arbitrary Decisions

The Delhi High Court in MRF Limited v. Assistant Commissioner of CGST & Central Excise [W.P.(C) 4262/2020] intervened where an advance ruling was found to be arbitrary and unreasonable:

“Even decisions of specialized authorities like the AAR and AAAR must satisfy the Wednesbury principles of reasonableness. A ruling that no reasonable authority could have reached is amenable to correction through judicial review.”

Limitations on Judicial Review

While constitutional courts have affirmed their power to review advance rulings, they have also recognized certain limitations:

- Deference to Specialized Expertise

In Sutherland Global Services Private Limited v. Union of India [2021-TIOL-1950-HC-DEL-GST], the Delhi High Court acknowledged the specialized expertise of AARs and AAARs:

“Constitutional courts must approach the review of advance rulings with appropriate judicial restraint, recognizing the specialized expertise of these authorities in GST matters. Mere disagreement with the interpretation adopted by these authorities would not warrant judicial intervention.”

- Alternative Remedy Consideration

The Gujarat High Court in Britannia Industries Ltd. v. Union of India [2020-TIOL-1454-HC-AHM-GST] emphasized the need to exhaust statutory remedies before seeking judicial review:

“The extraordinary jurisdiction under Article 226 should not ordinarily be exercised when the statute provides an alternative remedy. An aggrieved applicant should first approach the Appellate Authority for Advance Ruling before seeking judicial review, unless exceptional circumstances warrant direct intervention.”

- Self-Imposed Restraint on Questions of Fact

In Smartworks Coworking Spaces Private Limited v. AAR, Delhi [W.P.(C) 8496/2021], the Delhi High Court declined to interfere with factual findings:

“Constitutional courts exercising writ jurisdiction should refrain from reassessing factual determinations made by the AAR or AAAR. Judicial review in such cases is limited to examining whether the factual findings are based on relevant material and are not perverse.”

Key Judicial Decisions on GST Advance Rulings and Their Review

High Court Decisions

- Sony India Pvt. Ltd. v. Authority for Advance Ruling [2022-TIOL-1421-HC-DEL-GST]

The Delhi High Court addressed the question of whether an AAR’s interpretation of the GST law could be reviewed under Article 226. The court held:

“While the AAR’s determinations are binding within the statutory framework, they remain subject to the High Court’s constitutional oversight. When an interpretation adopted by the AAR is manifestly erroneous and has significant legal implications, the High Court can exercise its writ jurisdiction to correct such error, despite the finality accorded to advance rulings under Section 103.”

- Jumbo Bags Ltd. v. The Appellate Authority for Advance Ruling [2021-TIOL-2142-HC-MAD-GST]

The Madras High Court examined the scope of review over AAARs and observed:

“The appellate authority under GST is not merely an administrative body but exercises quasi-judicial functions that significantly impact taxpayers’ rights. The High Court’s power to review such decisions stems not just from detecting jurisdictional errors but extends to ensuring that these authorities function within the legal framework and adhere to principles of reasoned decision-making.”

- ABB India Limited v. The Authority for Advance Ruling [2022-TIOL-53-HC-KAR-GST]

The Karnataka High Court set an important precedent by clarifying the relationship between advance rulings and established judicial precedents:

“An Authority for Advance Ruling, despite its specialized role, cannot issue rulings that contradict binding precedents of the High Court or Supreme Court. Such rulings would suffer from a fundamental legal infirmity warranting intervention through judicial review.”

Supreme Court Guidance

While the Supreme Court has not issued comprehensive guidelines specifically on judicial review of GST advance rulings, its observations in analogous contexts provide valuable guidance.

In Godrej & Boyce Manufacturing Company Ltd. v. Commissioner of Income Tax (2017) 7 SCC 421, dealing with advance rulings under income tax law, the Supreme Court noted:

“The power of judicial review over specialized tribunals or authorities must be exercised with circumspection, recognizing their domain expertise. However, this restraint cannot extend to situations where such authorities act in excess of jurisdiction, commit errors of law, violate principles of natural justice, or reach conclusions that no reasonable authority could have reached.”

This approach, while articulated in the income tax context, offers a framework applicable to GST advance rulings as well.

Procedural Aspects of Judicial Review

Standing to Challenge Advance Rulings

A critical procedural aspect concerns who can challenge an advance ruling through judicial review. Section 103 states that advance rulings are binding only on the applicant and the concerned officers. However, judicial precedents have expanded the scope of standing:

In Bahl Paper Mills Ltd. v. State of Madhya Pradesh [2022-TIOL-987-HC-MP-GST], the Madhya Pradesh High Court recognized the standing of similarly situated taxpayers:

“While an advance ruling is statutorily binding only on the applicant and concerned officers, its precedential effect cannot be ignored. Where a ruling has industry-wide implications or affects a class of taxpayers similarly situated, such taxpayers have the requisite locus standi to challenge the ruling through judicial review, though they were not applicants before the AAR.”

Timeframe for Judicial Review

Unlike the 30-day limitation period for statutory appeals to AAAR or NAAR, there is no explicit limitation period for seeking judicial review. However, courts have applied the doctrine of laches:

In Hinduja Leyland Finance Ltd. v. Commissioner of GST & Central Excise [2021-TIOL-1652-HC-MAD-GST], the Madras High Court noted:

“While no rigid timeframe governs the exercise of writ jurisdiction, unreasonable delay in challenging an advance ruling may disentitle the petitioner to relief, particularly where significant financial arrangements or business decisions have been made in reliance on the ruling.”

Interim Relief Pending Judicial Review

The question of interim relief during pendency of judicial review has also been addressed by courts:

In Nipro India Corporation Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India [2020-TIOL-1591-HC-DEL-GST], the Delhi High Court granted interim relief suspending the operation of an advance ruling:

“Where prima facie the advance ruling appears to suffer from serious legal infirmities and its immediate implementation would cause irreparable harm to the petitioner, the High Court may grant interim relief suspending its operation, subject to appropriate conditions to balance competing interests.”

Challenges in the Current Framework of GST Advance Rulings

Conflicting Rulings Across States

One of the most significant challenges in the current framework is the issuance of conflicting advance rulings by AARs in different states on identical issues. While the introduction of NAAR was intended to address this issue, its delayed operationalization has perpetuated uncertainty.

In Integrated Decisions and Systems India Pvt. Ltd. v. State of Maharashtra [2021-TIOL-1774-HC-MUM-GST], the Bombay High Court highlighted this problem:

“The proliferation of contradictory advance rulings across states on identical issues undermines the very purpose of the advance ruling mechanism – to provide certainty and uniformity in tax treatment. This divergence necessitates a more robust system of judicial review to harmonize interpretations until the National Appellate Authority becomes fully operational.”

Limited Technical Expertise in Constitutional Courts

Another challenge concerns the technical expertise required to review complex GST matters. In Torrent Power Ltd. v. Union of India [2020-TIOL-1126-HC-AHM-GST], the Gujarat High Court acknowledged this limitation:

“Constitutional courts, while equipped to address questions of law and jurisdiction, may face challenges in navigating the technical complexities of GST classification and valuation. This reality calls for a balanced approach that respects the specialized expertise of AARs while ensuring adherence to legal principles.”

Potential for Regulatory Uncertainty

The interplay between advance rulings and judicial review can create regulatory uncertainty, as noted by the Calcutta High Court in Manyavar Creations Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India [2021-TIOL-1548-HC-KOL-GST]:

“The possibility that advance rulings, despite their intended finality, may subsequently be overturned through judicial review creates a layer of uncertainty for taxpayers. This tension between finality and reviewability requires careful navigation to maintain the efficacy of the advance ruling mechanism.”

Comparative Analysis with Other Jurisdictions

United Kingdom’s Approach

The United Kingdom’s tax ruling system allows for judicial review of advance rulings issued by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC). In R (on the application of Glencore Energy UK Ltd) v. HMRC [2017] EWCA Civ 1716, the Court of Appeal established that rulings could be reviewed for errors of law, procedural impropriety, or irrationality – a framework similar to India’s evolving approach.

Australian Model

Australia’s private ruling system under the Taxation Administration Act 1953 explicitly provides for judicial review, with the Administrative Appeals Tribunal and Federal Court having jurisdiction to review rulings. This structured approach provides greater certainty regarding the reviewability of rulings.

Lessons from European Union

The European Union’s VAT Directive includes provisions for advance rulings with varying approaches to judicial review across member states. The Court of Justice of the European Union has emphasized the importance of effective judicial protection, a principle that resonates with India’s constitutional framework.

Reform Proposals for Advance Rulings under GST

Statutory Recognition of Judicial Review

A potential reform could involve explicit statutory recognition of the power of High Courts and the Supreme Court to review advance rulings, clarifying the grounds, procedure, and limitations of such review. This would provide greater certainty to taxpayers and tax authorities alike.

Section 103 could be amended to include a provision such as:

“Notwithstanding the binding nature of advance rulings as specified in this section, nothing in this Act shall be construed to limit the constitutional power of the High Courts under Article 226 or the Supreme Court under Articles 32 and 136 to review such rulings on grounds of jurisdictional error, error of law, violation of natural justice, or manifest unreasonableness.”

Enhanced Technical Capacity in Courts

Establishing specialized GST benches within High Courts, comprising judges with taxation expertise, could enhance the quality of judicial review. Additionally, provisions for technical members or expert advisors could be introduced to assist courts in navigating complex GST issues.

Streamlined Procedure for Challenges

Developing a streamlined procedure specifically for challenges to advance rulings could enhance efficiency. This might include:

- Special format for petitions challenging advance rulings

- Accelerated timelines for disposal

- Standardized requirements for interim relief

Publication and Precedential Value

Mandating the publication of all advance rulings and judicial decisions reviewing them, along with clear guidelines on their precedential value, would enhance transparency and consistency in the GST regime.

Conclusion

The judicial review of advance rulings under GST represents a delicate balancing act between administrative finality and constitutional oversight. As the jurisprudence in this area continues to evolve, it is increasingly apparent that constitutional courts play a vital role in ensuring that the advance ruling mechanism fulfills its intended purpose of providing certainty while adhering to fundamental legal principles.

The current framework, characterized by limited statutory appeal provisions and the inviolable power of judicial review, creates both challenges and opportunities. The challenges include potential uncertainty, inconsistent approaches across jurisdictions, and questions about the appropriate scope of review. The opportunities lie in the potential for courts to harmonize interpretations, correct jurisdictional overreach, and ensure adherence to principles of natural justice.

As the GST regime matures, a more structured approach to judicial review of advance rulings is likely to emerge, potentially incorporating elements from other jurisdictions while respecting India’s unique constitutional framework. This evolution will require thoughtful engagement from legislature, judiciary, tax authorities, and taxpayers to develop a system that balances efficiency, certainty, expertise, and constitutional values.

The path forward lies not in restricting judicial review but in refining its exercise to ensure that it enhances rather than undermines the advance ruling mechanism. Such refinement, coupled with operational improvements to the AAR, AAAR, and NAAR framework, would strengthen India’s GST system by providing taxpayers with the dual benefits of administrative expertise and judicial safeguards.

In the final analysis, the scope and limitations of judicial review of advance rulings under GST reflect broader constitutional principles that balance administrative efficiency with legal oversight. The evolving jurisprudence in this area will play a crucial role in shaping the future of India’s GST regime, ensuring that it remains both technically sound and constitutionally compliant. As courts continue to clarify the contours of judicial review in this context, taxpayers, practitioners, and administrators would be well-advised to monitor these developments closely, recognizing their significant implications for tax planning, compliance, and dispute resolution strategies.

Preferential Allotment vs. Rights Issue: Regulatory Arbitrage or Flexibility?

Introduction

Capital raising represents one of the most fundamental functions of securities markets, allowing companies to finance growth, innovation, and operational requirements. In India, companies seeking to raise additional capital after their initial public offerings have several instruments at their disposal, with preferential allotments and rights issues standing out as the predominant mechanisms. These two routes to capital acquisition operate under distinct regulatory frameworks, creating differences in procedural requirements, pricing methodologies, disclosure obligations, and timeline constraints. The disparities have led to ongoing debate about whether these differing regimes create opportunities for regulatory arbitrage or simply offer necessary flexibility to accommodate diverse corporate funding needs. This article examines the regulatory landscapes governing preferential allotment vs. rights issue in India, analyzes the significant differences between these frameworks, explores how companies navigate these divergent paths, and evaluates whether regulatory harmonization or continued differentiation better serves market efficiency and investor protection.

Regulatory Framework Governing Preferential Allotments

Preferential allotments in India are governed primarily by the SEBI (Issue of Capital and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2018 (ICDR Regulations), specifically Chapter V, which replaced the earlier ICDR Regulations of 2009. This regulatory framework has evolved through multiple amendments, reflecting SEBI’s ongoing efforts to balance issuer flexibility with investor protection.

Section 42 of the Companies Act, 2013, read with Rule 14 of the Companies (Prospectus and Allotment of Securities) Rules, 2014, provides the statutory foundation for preferential issues, establishing the basic corporate law requirements. However, for listed entities, the more detailed and stringent SEBI regulations take precedence through Regulation 158-176 of the ICDR Regulations.

The ICDR Regulations define a preferential issue as “an issue of specified securities by a listed issuer to any select person or group of persons on a private placement basis.” This definition highlights the selective nature of these offerings, which are typically directed toward specific investors rather than the general shareholder base or public.

The regulatory framework imposes several key requirements on preferential allotments:

Regulation 160 establishes eligibility criteria for issuing preferential allotments, requiring that “the issuer is in compliance with the conditions for continuous listing of equity shares as specified in the listing agreement with the recognised stock exchange where the equity shares of the issuer are listed.” Furthermore, all existing promoters and directors must not be declared fugitive economic offenders or willful defaulters.

Pricing methodology constitutes perhaps the most critical aspect of preferential allotment regulation. Regulation 164(1) prescribes that the minimum price for frequently traded shares shall be higher of: “the average of the weekly high and low of the volume weighted average price of the related equity shares quoted on the recognised stock exchange during the twenty six weeks preceding the relevant date; or the average of the weekly high and low of the volume weighted average price of the related equity shares quoted on a recognised stock exchange during the two weeks preceding the relevant date.”

Lock-in requirements form another crucial protective measure. Regulation 167(1) mandates that “the specified securities, allotted on a preferential basis to the promoters or promoter group and the equity shares allotted pursuant to exercise of options attached to warrants issued on a preferential basis to the promoters or the promoter group, shall be locked-in for a period of three years from the date of trading approval granted for the specified securities or equity shares allotted pursuant to exercise of the option attached to warrant, as the case may be.”

For non-promoter allottees, Regulation 167(2) prescribes a reduced lock-in period of one year from the date of trading approval. These lock-in provisions aim to prevent immediate post-issuance securities dumping and ensure longer-term commitment from allottees.

The ICDR Regulations also impose substantial disclosure requirements through Regulation 163, mandating that the explanatory statement to the notice for the general meeting must contain specific information including objects of the preferential issue, maximum number of securities to be issued, and intent of the promoters/directors/key management personnel to subscribe to the offer.

In terms of procedural timeline, preferential allotments must be completed within a finite period. Regulation 170 stipulates that “an allotment pursuant to the special resolution shall be completed within a period of fifteen days from the date of passing of such resolution.” This tight timeline ensures that market conditions reflected in the pricing formula remain reasonably current at the time of actual allotment.

Regulatory Framework Governing Rights Issues

Rights issues operate under a distinctly different regulatory framework, primarily governed by Chapter III of the SEBI ICDR Regulations, 2018 (Regulations 60-98) and sections 62(1)(a) of the Companies Act, 2013.

Section 62(1)(a) of the Companies Act establishes the fundamental premise of rights issues: “where at any time, a company having a share capital proposes to increase its subscribed capital by the issue of further shares, such shares shall be offered to persons who, at the date of the offer, are holders of equity shares of the company in proportion, as nearly as circumstances admit, to the paid-up share capital on those shares.”

Unlike preferential allotments, rights issues embody the principle of pre-emptive rights, allowing existing shareholders to maintain their proportional ownership in the company. Regulation 60 of the ICDR Regulations defines a rights issue as “an offer of specified securities by a listed issuer to the shareholders of the issuer as on the record date fixed for the said purpose.”

The regulatory framework for rights issues contains several distinctive features:

Pricing flexibility represents one of the most significant differences from preferential allotments. Regulation 76 simply states that “the issuer shall decide the issue price before determining the record date which shall be determined in consultation with the designated stock exchange.” This provision grants issuers considerable latitude in pricing rights issues, without mandating any specific pricing formula. In practice, rights issues are typically priced at a discount to the current market price to incentivize shareholder participation.

Disclosure requirements for rights issues are comprehensive but tailored to the nature of these offerings. Regulation 72 mandates detailed disclosures in the draft letter of offer including risk factors, capital structure, objects of the issue, and tax benefits, among other information. While these requirements ensure investor protection through transparency, they differ from preferential allotment disclosures in their focus on general shareholders rather than specific allottees.

Timeline provisions for rights issues are more accommodating than those for preferential allotments. Regulation 95 states that “the issuer shall file the letter of offer with the designated stock exchange and the Board before it is dispatched to the shareholders.” After SEBI observations, Regulation 88 requires that “the issuer shall file the letter of offer with the designated stock exchange and the Board before it is dispatched to the shareholders.” The regulations permit a period of up to 30 days for the issue to remain open, providing more operational flexibility compared to preferential allotments.

A distinctive aspect of rights issues is the tradability of rights entitlements. Regulation 77 explicitly states that “the rights entitlements shall be tradable in dematerialized form.” This tradability allows shareholders who do not wish to subscribe to their entitlements to nevertheless capture value by selling these rights to others who may value them more highly.

Regulatory Differences: Preferential Allotment vs. Rights Issue

Several significant disparities between the regulatory frameworks of Preferential Allotment vs. Rights Issue create potential avenues for regulatory arbitrage, where companies might strategically select one route over another based not on fundamental business needs but on regulatory advantages.

Pricing Methodology Disparities in Preferential Allotment and Rights Issue

The most conspicuous disparity relates to pricing methodology. While preferential allotments are subject to the rigid pricing formula under Regulation 164 based on historical trading prices, rights issues permit issuers to determine prices without regulatory prescription. This distinction has profound implications for capital raising in volatile market conditions.

In Tata Motors Ltd v. SEBI (SAT Appeal No. 25 of 2015), the Securities Appellate Tribunal observed: “The pricing formula for preferential allotments serves the important regulatory purpose of preventing abuse through artificially depressed issuance prices that could dilute existing shareholders’ value. However, this protection becomes unnecessary in rights issues where all existing shareholders have proportionate participation rights, eliminating the dilution concern that motivates preferential pricing regulations.”

The case of Reliance Industries’ 2020 rights issue illustrates this disparity’s practical significance. The company raised ₹53,124 crore through a rights issue priced at ₹1,257 per share, representing a 14% discount to the market price at announcement. Had the company pursued a preferential allotment, the ICDR formula would have required a significantly higher price, potentially jeopardizing the issue’s success given prevailing market uncertainty during the pandemic.

Flexibility in Investor Selection

Preferential allotments allow companies to selectively choose their investors, potentially bringing in strategic partners or institutional investors with specific expertise or long-term commitment. Rights issues, conversely, must be offered proportionately to all existing shareholders, though undersubscribed portions may eventually be allocated at the board’s discretion.

In Eicher Motors Limited v. SEBI (2018), SAT recognized this distinction’s legitimate business purpose: “The regulatory distinction between preferential allotments and rights issues reflects the fundamentally different purposes these capital raising mechanisms serve. Preferential allotments facilitate strategic capital partnerships and targeted ownership structures, while rights issues prioritize existing shareholder preservation of proportional ownership. These distinct commercial objectives justify different regulatory approaches.”

Timeline and Procedural Requirements

Preferential allotments offer speed advantages, with Regulation 170 requiring completion within 15 days of shareholder approval. Rights issues involve more extended timelines, including SEBI review periods and 15-30 day subscription windows. This temporal difference can be decisive during periods of market volatility or when companies face urgent capital needs.

The Supreme Court acknowledged this distinction’s practical importance in SEBI v. Burman Forestry Limited (2021): “Regulatory timelines serve different purposes in different capital raising contexts. The expedited timeline for preferential allotments recognizes the typical urgency and targeted nature of such fundraising, while the more deliberate rights issue process reflects the broader shareholder engagement these offerings entail.”

Lock-in Period Differences: Preferential Allotments vs. Rights Issues

Preferential allotments impose significant lock-in requirements—three years for promoter group allottees and one year for others. In contrast, shares issued through rights offerings face no regulatory lock-in periods. This distinction can significantly impact investor willingness to participate, particularly for financial investors with defined investment horizons.

In Kirloskar Industries Ltd v. SEBI (SAT Appeal No. 41 of 2020), the tribunal observed: “Lock-in requirements serve as an important protection against speculative issuances in preferential allotments, where selective investor participation creates potential for market manipulation. These concerns are absent in rights issues where all shareholders receive proportionate participation opportunities, justifying the regulatory distinction regarding lock-in periods.”

Landmark Decisions on Preferential Allotment vs. Rights Issue

Several landmark judicial decisions have shaped the interpretation and application of these divergent regulatory frameworks, providing crucial guidance on their boundaries and interrelationships.

Distinguishing Between Regulatory Regimes: Sandur Manganese & Iron Ores Ltd. v. SEBI (2016)

This pivotal case addressed the fundamental question of how to categorize capital raises when they contain elements of both preferential allotments and rights issues. Sandur Manganese proposed an issue to existing shareholders but with disproportionate entitlements based on willingness to participate.

SAT held: “The defining characteristic of a rights issue under Regulation 60 is proportionate offering to all shareholders based on existing shareholding percentages. Any departure from this foundational principle renders the issue a preferential allotment subject to Chapter V requirements, regardless of whether the offer is extended only to existing shareholders. The regulatory framework does not permit hybrid instruments that selectively apply favorable elements from both regimes.”

This decision established a bright-line rule preventing companies from structuring offerings to arbitrage between regulatory regimes, affirming that the substance rather than mere form determines regulatory classification.

Testing the Boundaries: Fortis Healthcare Ltd. v. SEBI (2018)

In this significant case, Fortis Healthcare structured a capital raise as a rights issue but with an accelerated timetable and abbreviated disclosure process. When challenged by SEBI, the company argued that the urgency of its capital requirements justified procedural departures.

SAT rejected this argument: “The ICDR Regulations establish distinct and comprehensive regulatory frameworks for different capital raising mechanisms. The specific procedural requirements for rights issues under Chapter III are not discretionary guidelines but mandatory regulatory requirements. Commercial exigency, while understandable, cannot justify regulatory circumvention. Companies facing urgent capital needs must select the appropriate regulatory pathway based on their circumstances rather than attempting to modify regulatory requirements to suit their preferences.”

This ruling reinforced the integrity of the regulatory boundaries between different capital raising mechanisms and clarified that business necessity does not create implicit regulatory exceptions.

Clarifying Promoter Participation: Tata Steel Ltd. v. SEBI (2019)

This case addressed the intersection of promoter participation across different capital raising mechanisms. Tata Steel proposed a rights issue with a standby arrangement whereby the promoter would subscribe to any unsubscribed portion. SEBI initially classified this arrangement as a preferential allotment requiring compliance with the stricter pricing formula.

SAT overruled this interpretation: “Promoter underwriting of unsubscribed portions in rights issues does not transform the fundamental character of the offering from a rights issue to a preferential allotment. The key distinction lies in the initial proportionate opportunity afforded to all shareholders. The subsequent allocation of unsubscribed shares, whether to promoters or other subscribing shareholders, remains within the rights issue framework provided the initial rights were offered proportionately.”

This decision clarified that promoter support for rights issues through standby arrangements remains within the rights issue regulatory framework, providing important guidance on structuring such offerings.

Addressing Potential Abuse: SEBI v. Bharti Televentures Ltd. (2021)

This landmark Supreme Court case addressed SEBI’s authority to intervene when companies potentially abuse the regulatory distinctions between capital raising mechanisms. Bharti Televentures had conducted a rights issue priced significantly below market value, immediately followed by a preferential allotment to institutional investors at market price. SEBI alleged this sequential structure artificially circumvented preferential pricing requirements.