Calculation of Salary Under 7th Central Pay Commission(7th Pay Matrix)

Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

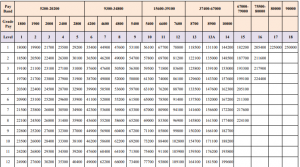

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

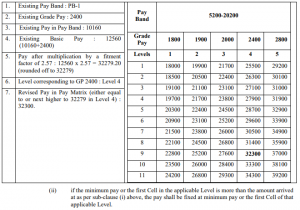

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

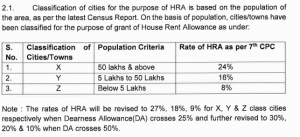

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

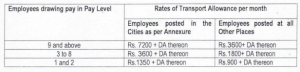

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

- Appeal Lawyers – Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Bail Lawyers | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Best High Court Advocate, High Court Lawyer, Corporate, NCLT, Taxation, Arbitration, DRT, Customs, Revenue, Civil and Criminal Lawyers in Ahmedabad

- Bhatt & Joshi Associates

- Blog

- DISCLAIMER

- Focus Sectors

- Biotechnology Sector – Insights, regulatory landscape & legal expertise

- Empowering Defence Industry: Bhatt & Joshi Associates’ Legal Expertise

- India’s Media Sector

- Insurance

- Motor Vehicle Act in India

- Navigating the Booming Electronics Manufacturing Sector

- Navigating the Regulatory Landscape of India’s Dynamic Chemical Sector

- Pharmaceutical Industry in India – Regulatory Framework & Legal Services

- Telecom

- Get In Touch

- Get in Touch – Bhatt & Joshi Associates Best High Court Advocates & Lawyers

- News & Media

- Other

- Our Expertise

- Privacy Policy

- Sample

- Sample

- Service Lawyer in Gujarat | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Services

- Admiralty Lawyer | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Civil Lawyer in Ahmedabad

- Civil Lawyers Copy

- Constitution Lawyers | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Environmental Lawyers

- FEMA Lawyer | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Land Acquisition Lawyers

- SEBI Lawyers Gujarat | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Writ Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyer in Ahmedabad

- Gujarat Land Revenue Lawyer | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Property Lawyer in Ahmedabad | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Service Lawyers/Government Job Lawyers

- Arbitration Lawyer | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Bail & Anticipatory Bail Lawyers

- Quashing Lawyers

- Best Corporate Lawyers in India | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Taxation Lawyer | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Family Lawyers

- NDPS Lawyer | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Banking Lawyers Copy

- Banking Lawyers in Ahmedabad | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Charity & Trust Lawyers

- Team

- Thank You

- Thank You –

- Writ Petition Lawyer | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- About Us

- Customs Appeal | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Forums we represent

- Commercial Court | Commercial Court Lawyers & Commercial Court Advocates

- Competition Commission | Competition Commission Lawyers

- Enforcement Directorate | Enforcement Directorate Lawyers

- GST Appeal | GST Appeal Lawyers & GST Appeal Advocates

- SEBI (Securities and Exchange Board of India) | SEBI Lawyers & Securities Lawyers

- Arbitration

- Gujarat High Court | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad High Court

- Our Services

- Supreme Court | Supreme Court Lawyers & Supreme Court Advocates

- NCLT Copy

- NCLT Lawyers | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- DRT Ahmedabad | Debt Recovery Tribunal | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Contact Us

- Gujarat Revenue Tribunal | Bhatt & Joshi Associates | Ahmedabad

- Careers

- Opportunities

- Special Secretary Revenue Dept(SSRD) | SSRD Lawyer

- CIT Appeals & ITAT

- Our Blog

- Arbitration

- GRT (Gujarat Revenue Tribunal) Copy

- CIT Appeals & ITAT Copy

- CAT (Central Administrative Tribunal)

Feature Title

Feature content

Whatsapp

Whatsapp